Maria Ana Castro Caldas de Aboim Inglez

m@aboiminglez.com

Architect and PhD candidate at the Department of Architecture of the Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (Da/UAL), Portugal. CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa.

TO cite this article:

INGLEZ, Maria Ana Castro Caldas de Aboim – The Pools of Bellinzona. Landscape | Architecture | Infrastructure. Estudo Prévio 24. Lisbon: CEACT/UAL – Centre for Architecture, City and Territory Studies of the Autonomous University of Lisbon, May 2024, p. 53-108. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/24.2

Received on September 19, 2024, and accepted for publication on October 17, 2024.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Piscinas de Bellinzona. Paisagem | Arquitetura | Infraestrutura

Absrtact

The Bellinzona Swimming Pools, designed by Aurelio Galfetti, Flora Ruchat-Roncati, and Ivo Trümpy, the result of a public competition and officially inaugurated in August 1970, represent a project of great architectural value. Built in Switzerland, more specifically in the Ticino region, the work has been listed as a cultural property of cantonal importance since 2010.

The aim is to demonstrate that the project seeks the identity of the place, aligning with the ongoing idea of fostering mobility, while pointing to pathways for its future expansion by transcending the boundaries set by the competition’s programme. It is important to clarify that the uniqueness of the proposal, demonstrated in the creation of a raised pathway six metres above the plain of intervention, surpasses, in its infrastructural design, the assumptions of a public facility, resolving, in a dual gesture of continuity and radicality, the territorial connection between the valley, Bellinzona, and the Ticino River.

The continuous changes to the general proposal, from the competition phase to its construction, will be studied through the analysis of primary sources available at the Archivio del Moderno, demonstrating that these changes are rooted in refinements underpinned by an incessant formal uncertainty. The numerous variations of the walkway profile developed throughout the project’s evolution will be addressed, with their synthesis being examined in the search for meaning in architecture. Echoes and influences will be presented, invoking territorial proposals to reinforce the defended proposition. The analysis of the work will be enriched through an interview with Nicola Navone, current deputy director of the Archivio del Moderno, who, alongside Bruno Reichelin, was responsible for the first monograph on the Piscinas, providing an important and exhaustive reading of the project. The longevity of the work will be observed, identifying what has flourished as well as what has been suppressed over time, defining the work as a seminal international project by achieving a rare triad: Landscape, Architecture, and Infrastructure.

Keywords: Bellinzona Swimming Pools, Aurelio Galfetti + Flora Ruchat-Roncati + Ivo Trümpy, Landscape, Infrastructure.

1. Dissemination

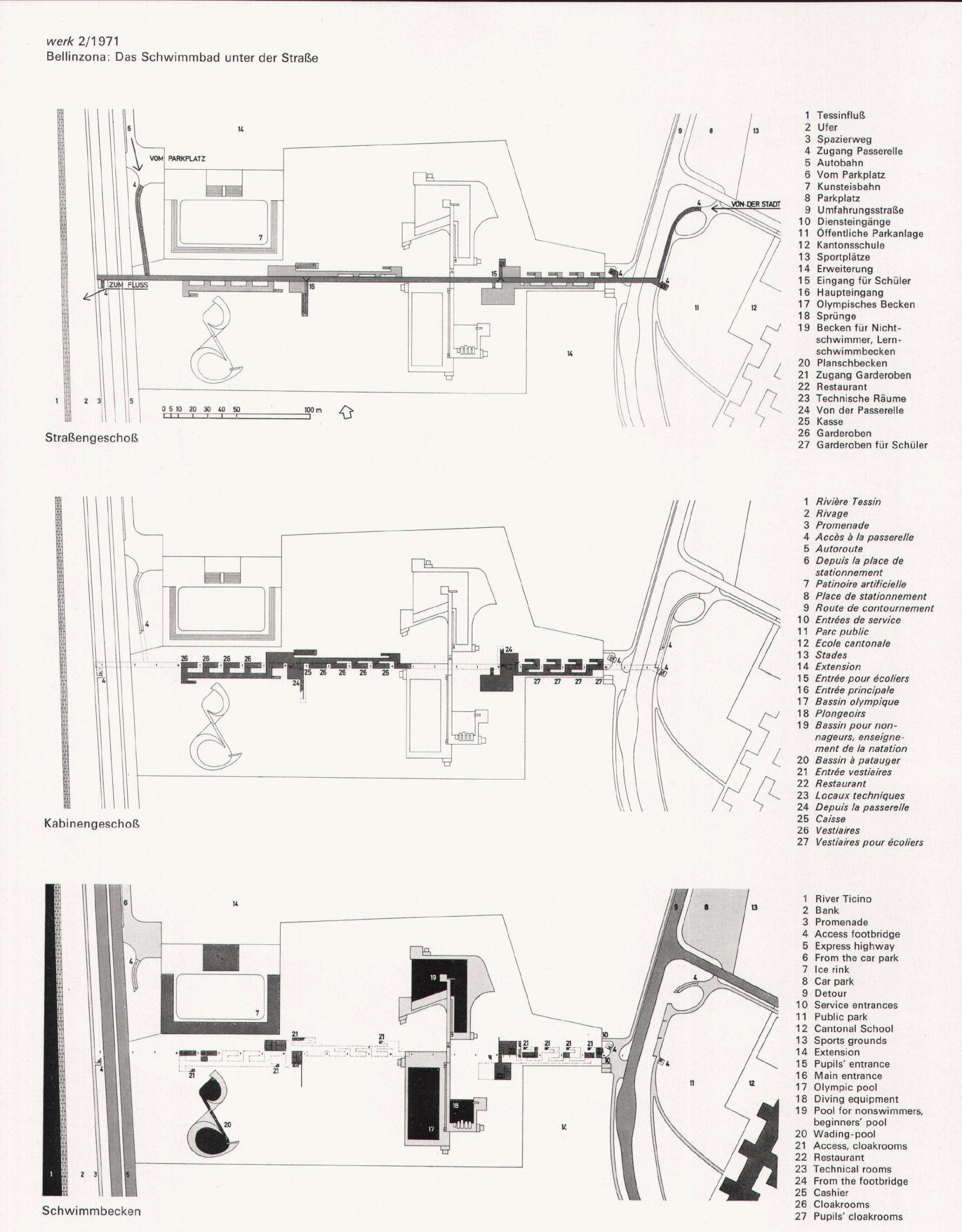

The Bellinzona Swimming Pools, designed by Aurelio Galfetti, Flora Ruchat-Roncati, and Ivo Trümpy, officially inaugurated in August 1970, resulted from a competition organised by the Municipality of Bellinzona, held between April and August 1967. Despite being announced in local newspapers, the project only gained its first significant publication in the field of architecture in February 1971, in issue 58, volume 2, of the magazine Werk, Switzerland’s leading architectural journal owned by the FAS – Federation of Swiss Architects.

In this publication, the work is presented alongside the Lancy and Zurzach Swimming Pools, designed by architects Paul Waltenspühl and Fritz Schwarz, respectively. All three projects reflect a period of municipal investment in public facilities associated with leisure spaces, supported by well-integrated and detailed structures, predominantly in concrete. While the Lancy and Zurzach projects follow more conservative approaches, albeit displaying formal virtuosity, the Bellinzona project transcends this programmatic response, demonstrating an innovative territorial vision. Prior to this dissemination, the winning proposal was published in the Rivista técnica [1], in various issues, with details of an informative nature.

Figure 1 – Plans published in Werk magazine, No. 2, issue 58, February 1971 (Source: E-Periodica – Das Werk: Architektur und Kunst = L’oeuvre: Architecture and Art – Retirement Homes – Swimming Pools).

Between the inauguration and its first significant dissemination, an initial attempt to publish the project in Casabella was made, without success, through efforts led by Bruno Reichlin [2], who was then an external collaborator for the magazine. This rejection may seem inconceivable, but it can be argued that works heralding something fundamental sometimes require time to “breathe” in order to become intelligible in their discourse and perceptible in their meaning.

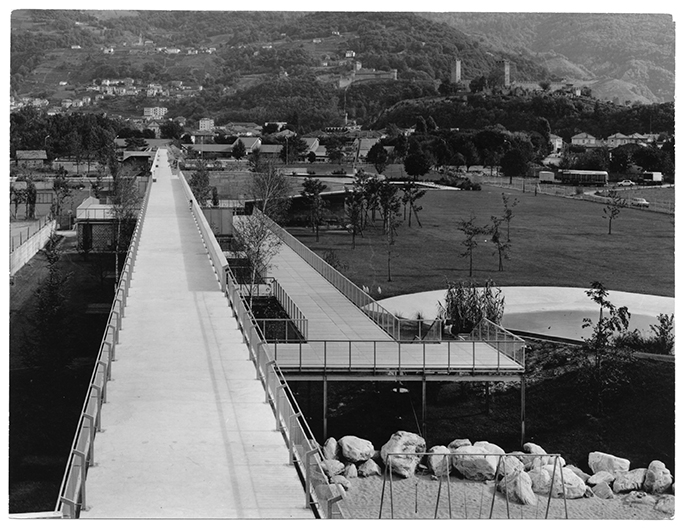

In the article published in Werk, written by Diego Peverelli [3], an architect also from Ticino, programmatic plans were featured alongside striking photographs of the work, taken by Peverelli himself and Pino Brioschi. These images, that still widely circulate today, reveal a depth of field that introduces territorial clarity. The credit for this first publication goes to Bruno Reichlin, who presented the project to Diego Peverelli, in an effort to overcome the initial editorial setback.

Figure 2 – Photograph by Pino Brioschi, 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, ALG).

A few years later, in 1975, an important exhibition was held at ETH Zurich, curated by Martin Steinmann [4] and Thomas Boga, entitled Tendenzen – Neue Architektur im Tessin. The term Tendenzen clearly reflected the influence of Aldo Rossi [5], though it faced criticism for the synthesis it implied, reducing its content to a uniform layer of ideas and meaning. The exhibition catalogue, printed in three editions between 1975 and 1976 due to growing demand, was republished as a facsimile version in 2010.

The catalogue accompanied the exhibition on its extensive journey across Europe and North America, propelling the architecture of Ticino—constructed between the 1960s and 1970s in this particular Swiss canton, closely connected to northern Italy in linguistic, cultural, and geographic terms—into the international spotlight. Among the 48 featured projects were the Bellinzona Swimming Pools. The project’s authors were part of a group of 21 Ticino architects, including notable figures such as Mario Botta [6], Peppo Brivio, Mario Campi, Tita Carloni, Bruno Reichlin, Fabio Reinhart, Luigi Snozzi [7] and Livio Vacchini [8], among others.

As for the exhibited works, which encompassed private houses, school facilities, and public buildings, some still under construction, the exhibition also showcased other projects by the designers of the Bellinzona Swimming Pools. These included the Ruchat House [9], in Morbio Inferiore, the Primary School of Riva San Vitale, the Viganello Kindergarten [10], in Lugano, as well as two projects by Aurelio Galfetti alone: the Kindergarten in Bedano [11] and the Rotalin House [12], in Bellinzona.

The format in which the design of the Bellinzona Swimming Pools is presented, without identification of its urban, social, and economic context, adhering to graphic standards consistent with the other proposals, as Irina Davidovici clarifies in her recent book The Autonomy of Theory: Ticino Architecture and Its Critical Reception [13], may have diminished its greatest strength, which can be summarised as an intelligent synthesis of critical site interpretation. The three plans presented, indicating only pathways, cabins, and pools, are the result of further graphic refinements made for the earlier publication in Werk.

The project began to gain recognition through an intriguing geometric composition. However, this appealing graphic representation may have undervalued its strong territorial component, which remains one of its greatest strengths.

The exhibition and its catalogue continue to resonate with mythical significance, especially in academic circles, marking a decisive moment in the history of Ticino architecture.

The magazine L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui published two significant articles in its 1977 edition: Francesco Dal Co’s critique, written in August 1976, of the Tendenzen exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, as well as a text titled Critique of Critique by Martin Steinmann and Bruno Reichlin. The same edition included the project, accompanied by the recurring plans of the Swimming Pools, along with some photographs and a brief text.

Francesco Dal Co is neither consensual, cautious, nor indirect, but rather highly critical of the choice of projects and their relevance within the field of architecture. He writes that the prevailing substance is insufficient, pointing out that “the impression left by the completed works falls far short of what was presented in the catalogue of the Tendenzen: Neue Architektur im Tessin exhibition. The discrepancy between reality and its representation is striking. The theoretical distance and ideological efforts employed by the authors of the catalogue to justify their choices raise a question: is there truly an architectural production in Ticino that warrants such an effort?” [14]

Despite his uncompromising stance, Dal Co highlights Flora Ruchat-Roncati, stating, “she conscientiously interprets Le Corbusier—in the house in Morbio, in the school in Riva San Vitale (realised in collaboration with Aurelio Galfetti and Ivo Trümpy), or in the leisure centre in Bellinzona.” [15] This observation takes on additional significance when he mentions, at the beginning of his critique, that in this geographical area of Ticino, “external influences remain marginal, and architectural production rarely provides its authors the opportunity to concretely develop and verify their research.” [16] To fully grasp Dal Co’s critique, it is necessary to contextualise it within its time and the architectural moment, which was undergoing a significant transition marked by critical reflections on the modern movement.

The dissemination of the project, following the aforementioned catalogue, took place through publications in Lotus International in 1977, the first volume of the journal Ianus in 1980, and Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme in 1982. In this latter publication, entitled Del Conocimiento a la Invención, Martin Dominguez [17] notes that, of all the works showcased in the Tendenzen exhibition, the one that most influenced a generation of architects was the Bellinzona Swimming Pools project. With a sense of longing and nostalgia, he even remarks that it “remains etched in our memory, representing, in a certain way, the entire body of work of the Ticino architects.” [18] The article, focused solely on Aurelio Galfetti with the aim of gaining deeper insight into his oeuvre, is accompanied by a significant interview with him. When discussing the Swimming Pools project, Galfetti explains that it was conceived

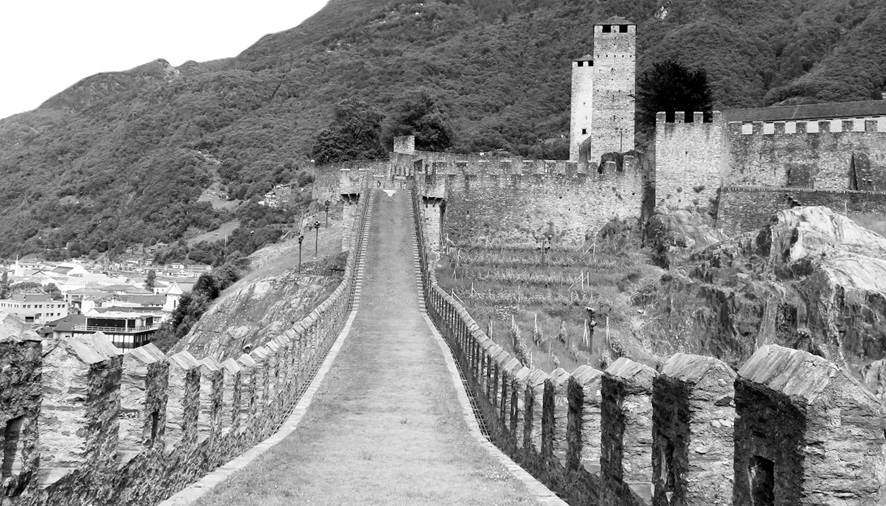

“as a unitary intervention in the landscape rather than as a series of diverse elements of the program grouped in a way more or less corresponding to the functional prerequisites. Le Corbusier spoke of the Roman aqueduct as an element that, by overcoming the scale of neighbouring houses, does not destroy but accentuates the qualities of the place. We took this idea of using the program as a pretext to propose an intervention that did not seek to integrate with the site, but which tried to give it a stronger identity. In fact, we thought that the walkway that connects and organizes all the elements of the program was a public element, a promenade, belonging to the system of walls that have defined the perimeter of Bellinzona since the Middle Ages. We built, if you will, a fragment of a wall.” [19]

It is interesting to highlight, in continuity with Galfetti’s words for Quaderns, what Stanislaus Von Moos [20], conveyed in 2001 in his text Castello Propositivo, Identity, Memory and Monumentality in Ticino 1970-2000:

“Rossi emphasizes that the rebuilding of the wall should serve, among other things, to create a link with the recently completed public pools designed by Galfetti, Ruchat, and Trümpy, whose design was probably conceived with Le Corbusier (Plan Obus for Algiers, 1931) in mind rather than Rossi. Could this be one of the few areas of intersection where Rossi and Le Corbusier’s ideas converge?” [21]

In the subsequent decades, several publications on Aurelio Galfetti’s work followed, such as the publication by Editorial Gustavo Gili in 1992, with an introduction by Mario Botta and production by Mirko Zardini, in which the swimming pool project is consistently acknowledged with due mentions. The work continues to be disseminated through various collective exhibitions, such as the Cuatro Arquitectos Suizos exhibition held in 1996 at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires, where Galfetti was featured alongside Mario Botta, Luigi Snozzi, and Livio Vacchini. It is worth noting that Galfetti delivered numerous lectures, both within Switzerland and abroad, in the ensuing years, demonstrating that the project maintained its relevance through his words.

In 2006, the Swiss Embassy in Portugal organised, in collaboration with the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Porto and the Department of Architecture at the University of Coimbra, an exhibition entitled “Ticinese Architecture in the World: References and Protagonists”, which took place in both Porto and Coimbra. The swimming pool project was included in the exhibition, and it is noteworthy that Galfetti was invited to deliver a lecture titled Tra terra e cielo: permanenza dell’architettura, followed by a debate with architect Gonçalo Byrne.

Later, in 2009, a small book entitled Il Progetto dello SpazioSpazo [22], named after a lecture by Aurelio Galfetti delivered in 2007 at USI Mendrisio (Università della Svizzera italiana), was published. When presenting the swimming pool project, Galfetti remarked, “we were interested in ‘space-time’, more specifically the space of walking, the space of movement.” [23]. It is worth adding that, 54 years later, the project has also evolved into a space of culture.

Regarding Flora Ruchat-Roncati, in the subsequent decades, publications about her work were fewer in number compared to other colleagues of the same generation, despite her continued intense dedication to the profession, teaching, and research. In this context, it is important to highlight the 1998 publication by Gta Verlag on her work, in which the swimming pool project is prominently mentioned.

Although this was a significant publication, it had limited dissemination beyond academic circles, a sphere where Flora gained notable recognition, becoming the first woman to be appointed full professor, with full rights and academic responsibilities, at ETH Zurich in 1984. Recently, her significance has been increasingly recognised through new research and publications at her university.

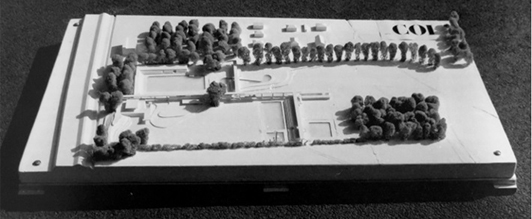

In 2009, an exhibition and accompanying seminar were held in Mendrisio, entitled Il Bagno di Bellinzona: l’opera e la sua salvaguardia, organised by Nicola Navone [24], with Franz Graf [25] and Bruno Reichlin. During the seminar, a roundtable discussion was held, bringing together the three authors of the project, along with Franz Graf, Martin Steinmann, representatives of the Municipality of Bellinzona, and the Department of Territory of the Canton of Ticino, to discuss the future of this facility, which at the time showed significant signs of wear and tear. The discussion also addressed a recurring concern associated with the predominant use of concrete in buildings from this period. A model of the project was constructed to support the understanding of the work, which is now preserved at the Archivio del Moderno. The model seeks abstraction, presented as a refined and intentional synthesis.

Figure 3 – Photograph of the model held at the Archivio del Moderno (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

As a result of the exhibition and catalogue held in Mendrisio, a monograph was published in 2010, curated by Nicola Navone and Bruno Reichlin, titled Il Bagno di Bellinzona di Aurelio Galfetti, Flora Ruchat-Roncati, Ivo Trümpy. It includes analytical texts by Martin Steinmann, Bruno Reichlin, Nicola Navone, Franz Graf, and others. Since 2021, the book has been in its third edition, although it remains published solely in Italian.

The monograph features numerous drawings from various stages of the project, ranging from the competition phase to its construction, supported by execution details sourced from the architects’ archives, donated to the Archivio del Moderno. The photographs, capturing different periods, illustrate the significant transformation of the landscape, while emphasising the path’s enduring prominence within its territory.

Despite the scale and abundance of trees, the photographs published in 2009 reveal a work in need of maintenance, from the worn and partially replaced wooden flooring to the deteriorated partitions. The project ages, remaining alive in its gesture, but at that time clearly requiring safeguarding efforts.

In 2013, following the death of Flora Ruchat-Roncati, a book titled Flora Ruchat-Roncati, le opere, la ricerca, l’insegnamento was published. Authored by Serena Maffioletti, Nicola Navone, and Carlo Toson, the book surprises those who, until then, knew little or nothing about Flora. Through her works, drawings, and texts, it provides a compelling demonstration of her journey in architecture.

The recently published book by Irina Davidovici, titled The Autonomy of Theory, Ticino Architecture and its Critical Reception, provides a pointed critique of the spread of Ticino architecture, attempting to understand “the role of the architectural discourse generated by implacable, often opaque, mechanisms of critical evaluation.” [26].

Despite the numerous exhibitions, countless publications in excerpts from books by the architect-authors, publications in specialised journals, and academic articles, it is evident that these are mostly from the various Swiss cantons, as if the very topography were an obstacle to their wider dissemination. However, it is important to highlight that both Università LUAV di Venezia and Politecnico di Milano have produced significant research on the work. Also absent from fundamental critical selections, such as those by Kenneth Frampton [27] or William J. R. Curtis [28], its territorial dimension loses strength when it is only perceived in the graphic bidimensionality of an appealing gesture.

Although the work is an important architectural reference for a generation of architects trained at Swiss architectural schools, notably ETH Zurich, EPFL in Lausanne, and especially USI Mendrisio, due to its proximity to the work and the significant role played by Galfetti, who was a professor and the first director of the latter, it is nonetheless noteworthy to highlight that, outside of this geographical context and beyond the areas close to northern Italy, the work gradually leaves few memories for those who do not visit it. And sometimes, to counteract this, it is revived with new analyses and interpretations, in a kind of eternal return.

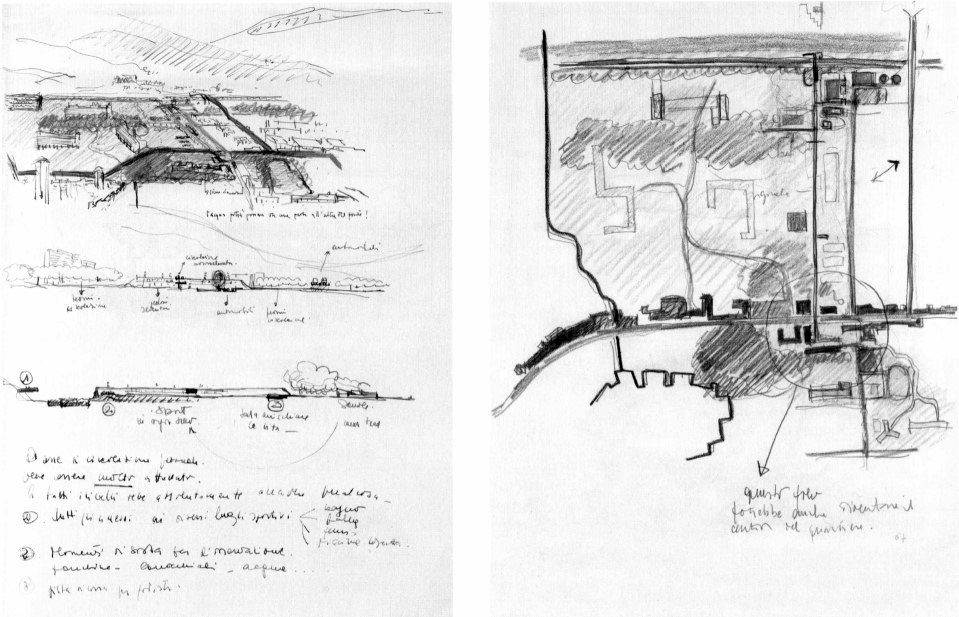

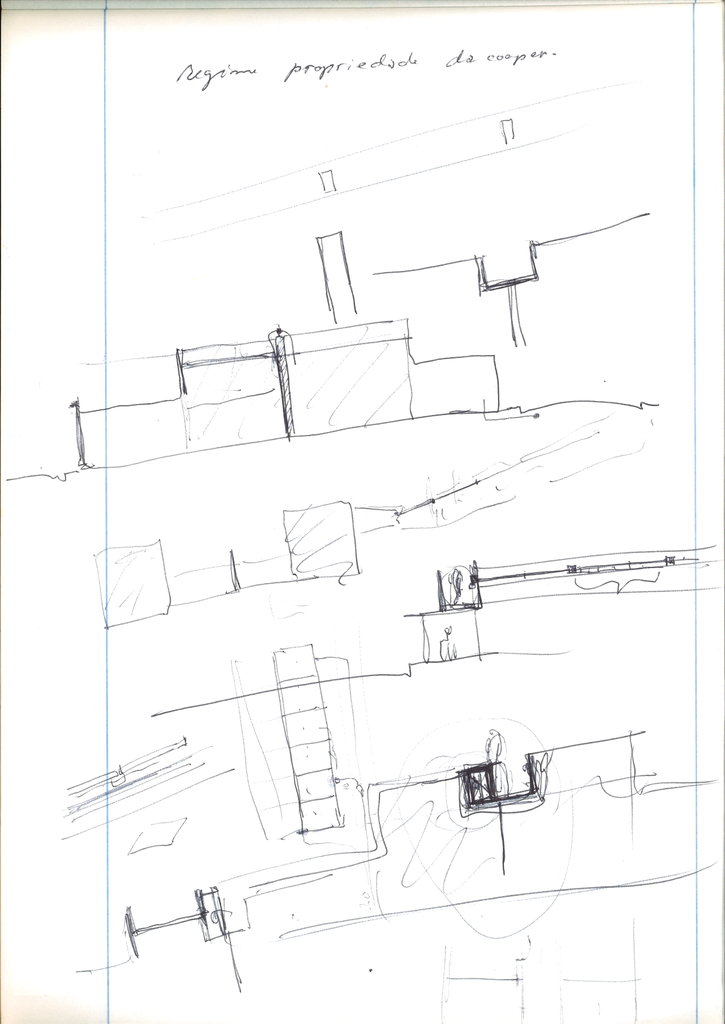

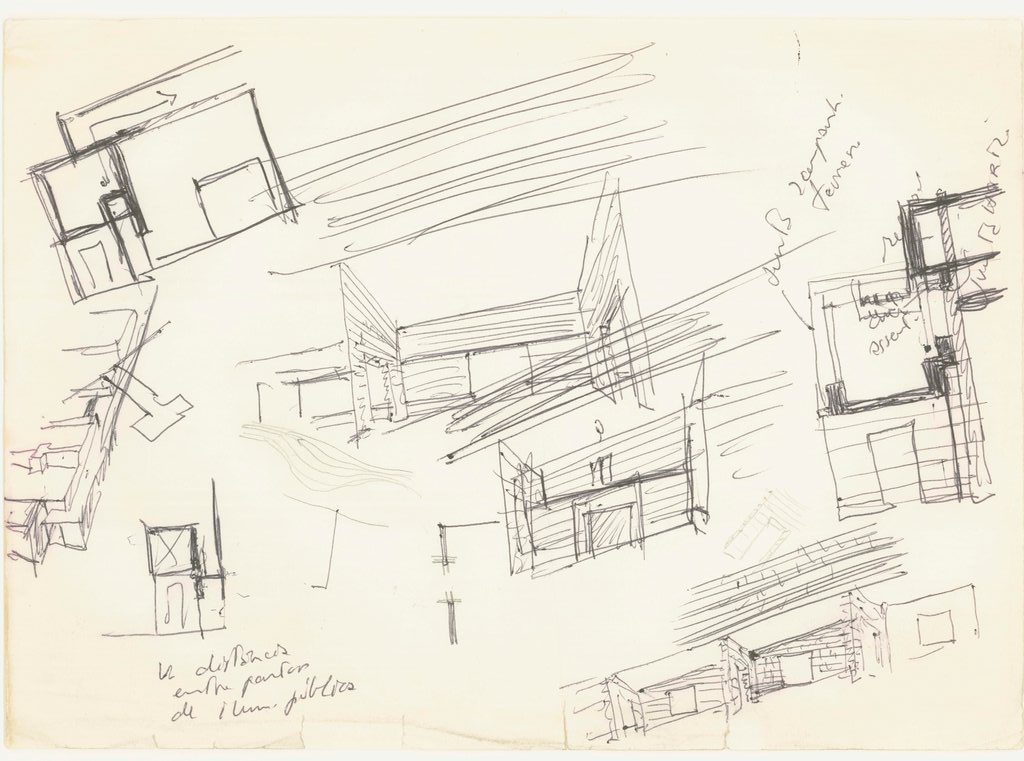

Demonstrating that the work remains alive and continues to reach different fields of dissemination, in a recent exhibition of drawings curated by Manuel Montenegro, Helen Thomas, and Marco Bakker, titled Begin Again. Fail Better, some drawings by Flora Ruchat-Roncati were selected and exhibited at the Kunstmuseum in Olten. Two of the drawings, already presented in the book Un Dialogo Ininterrotto, Studi su Flora Ruchat-Roncati [29], feature sketches for the swimming pool competition proposal, where connections to the site are explored and questioned. The site, marked by walls that stand out as territorial lines, has a significant influence on the gesture of the proposal.

Figure 4 – Sketches by Flora Ruchat-Roncati for the Pools of Bellinzona, 1967 (Source: Dagli Esordi Al Bagno Di Bellinzona, article by Nicola Navone, published in Un Dialogo Ininterrotto, Il Poligrafo, 2018).

2. 1964-1966

When analysing the time period between 1964 and 1966, the years preceding the announcement of the competition for the Swimming Pools, one can identify these as years marked by significant events and intense critical disciplinary production. The themes of mobility in cities began to influence urban design, and new social paradigms reversed the discourse, generating new architectural codes grounded in the city, the territory, and the landscape.Years earlier, Alison and Peter Smithson, pioneers in interpreting cities through their mobility frameworks, experimented with diagrams of pedestrian connections, referred to as streets-in-the-air [30]. These connected high-density housing, enabling patterns of movement by separating vehicular and pedestrian circuits, fostering urban comfort while simultaneously freeing up ground space.

Alison and Peter Smithson’s proposal for the Golden Lane [31], competition in 1952 identifies streets-in-the-air as spaces rather than corridors or balconies. This proposition of streets that invite life, where everything happens beyond the intensity of vehicular traffic—particularly significant in industrialised European cities—would undoubtedly influence an entire new generation of architects, whose social and ethical propositions fused the understanding and meaning of architecture.

Returning to the time period initially mentioned, the 13th Milan Triennial of 1964, curated by Umberto Eco and Vittorio Gregotti, defined Leisure as its theme. It marked the first time that a curatorial purpose addressed a reflection on both quantitative and qualitative definitions of leisure time, the role of consumption, and its relationship with working time.

In the 1982 preface to the re-edition of Vittorio Gregotti’s book The Territory of Architecture, Umberto Eco clarifies:

“The Trienniale was intended to explore the theme of ‘leisure’ in a more comprehensive manner, beyond simply showcasing objects and infrastructure projects. This was also a utopian theme, common during the post-war boom: the pursuit of free time as a means of liberation (or a pause) from the alienation of work. At the 1964 Triennale, we decided that the public should access the exhibitions through a labyrinthine journey, a series of audiovisual passages, where architecture, applied arts, painting, sculpture, cinema, and television come together in a critical discourse on the concept of leisure. We utilized the architectural space as a global concept to explore and challenge the utopias of architecture as a universal project.” [32]

Leisure (Tempo Libero), a complex theme with philosophical and utopian implications, opened up the possibility of rethinking the very way architecture was presented, shifting its focus to sociological connotations rather than merely formal propositions. Architecture, design, and art were asked to represent the moment of change by portraying the contemporary world and, in a critical stance, to reflect on the meaning of the term leisure.

Nicola Navone explains [33] that Vittorio Gregotti’s ideas held significant resonance within the architectural debate in Ticino, highlighting the relationship of friendship and admiration Gregotti shared with Peppo Brivio [34], a prominent architect and intellectual from Ticino. Together, they developed the unforgettable exhibition space known as Kaleidoscope, alongside Umberto Eco, Ludovico Meneghetti, and Giotto Stoppino, for the previously mentioned 13th Milan Triennial in 1964. This space, composed of inclined mirror planes, created an extensive reflective journey through space and time.

Figure 5 – Caleidoscopio, Introductory Section of an International Character, XIII Milan Triennale, 1964 (Source: Archivio Fotografico Triennale Milano, © Ancillotti).

Evoking the idea of mobility, Aldo Rossi and Luca Meda designed, for the aforementioned Triennial, an elevated iron-structured infrastructural access to the Palazzo dell’Arte in Milan. This intervention assigned a new function to its façade, transforming 3it into the support for a bridge with quadrangular and cylindrical pillars, sustaining a triangular configuration in its cross-section. These archetypal elements, positioned as a combination of urban artefacts, propose new paradigms composed of novel city elements, establishing distinct interpretations of fixed components tied to collective memory.

Figure 6 – Aldo Rossi and Luca Meda, Entrada Palazzo dell’arte, 13th Milan Triennale, 1964, (Source: Archivio Fotografico Triennale Milano, © Luca Meda).

In the following year, Le Corbusier presented the proposal for the Venice Hospital, contributing to perpetuate the fascination among an important generation of new architects, drawn to their Master, who avidly absorbed all his built and published work. The proposal for this facility delineates an urban fabric in radical continuity, introducing new territorial assumptions. It is no longer a gesture imposing a design upon the site but rather the existing urban fabric that defines its trajectory. Streets, connections, and squares, elevated above the water level, allow for its visibility, establishing strategies for the implementation of a dense facility for the city of Venice. The city’s history is not erased but translated, employing a modular design with multiple repetitions, replacing the traditional Venetian wooden foundations with concrete pillars. Much can be debated regarding the programmatic layout, natural lighting, and the user’s relationship with the space; however, it is important to highlight the innovative character of defining a mat-building [35], for a hospital. Modular construction, combined with a tectonic sensibility, gains significance within the disciplinary field, introducing new urban programmes integrated with pre-existing codes.

Everything was being prepared for the construction of this facility, characterised by its gesture and territorial scale, where the repetition of the module stands out as a means of shaping the city, surpassing its scale. However, Le Corbusier’s premature death in the same year, 1965, suspended its realisation.

New interpretations of the concepts of territory, city, and architecture were underscored by three major publications in 1966, which became key bibliographic references shaping architectural discourse and its meaning within this period: the incisive critical analysis Il territorio dell’architettura by Vittorio Gregotti; L’architettura della città by Aldo Rossi, an equally pivotal reference for the search for new lexicons in defining urban facts and theories about the city, examined as architecture; and Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture by Robert Venturi.

While Rossi emphasises, in the design of the city, the density of layers and the value of locus, Venturi engages with issues of communication, image, and the meaning of architecture. Gregotti, drawing upon themes of territory, landscape, anthropogeography, and history to address the uses and meanings of architecture, distinguishes himself by reflecting on the notion of habitability through the materials that constitute architecture.

3. Architects

Aurelio Galfetti (1936 – 2021), Flora Ruchat-Roncati (1937 – 2012) and Ivo Trümpy (1937), despite being relatively young at the time they submitted their proposal for the Bellinzona Swimming Pools competition, had already built several school buildings and private residences of notable urban and programmatic complexity. This accumulated experience, gained over several years of working together in Bedano (1962–1970), was undoubtedly crucial in enabling them to develop the Swimming Pools project, in a continuous pursuit of not only efficient construction solutions but also ethical ones. [36]

For a brief introductory note on each architect, it can be mentioned that Aurelio Galfetti, born in Lugano, graduated in 1960 from ETH Zurich. After his significant partnership with Flora Ruchat-Roncati and Ivo Trümpy, he continued, between 1970 and 1978, to collaborate with other equally impactful architects from Ticino, such as Livio Vacchini, Luigi Snozzi, Rino Tami [37] and Mario Botta.

In 1984, he was a guest professor at EPF Lausanne and, in 1987, at UP8 in Paris-Belleville. Together with Mario Botta, in 1996, he founded the Mendrisio Academy at the University of Italian Switzerland, serving as its director between 1996 and 2001 and as a professor at the institution until 2010. To this day, students and faculty alike hold fond memories of him, recognising him as one of the Academy’s central historical figures, often highlighting his great humanity. Nicola Navone further notes his remarkable generosity, coupled with his ability to view reality without nostalgia or regret, while upholding a deontological commitment to respecting the discipline. [38]

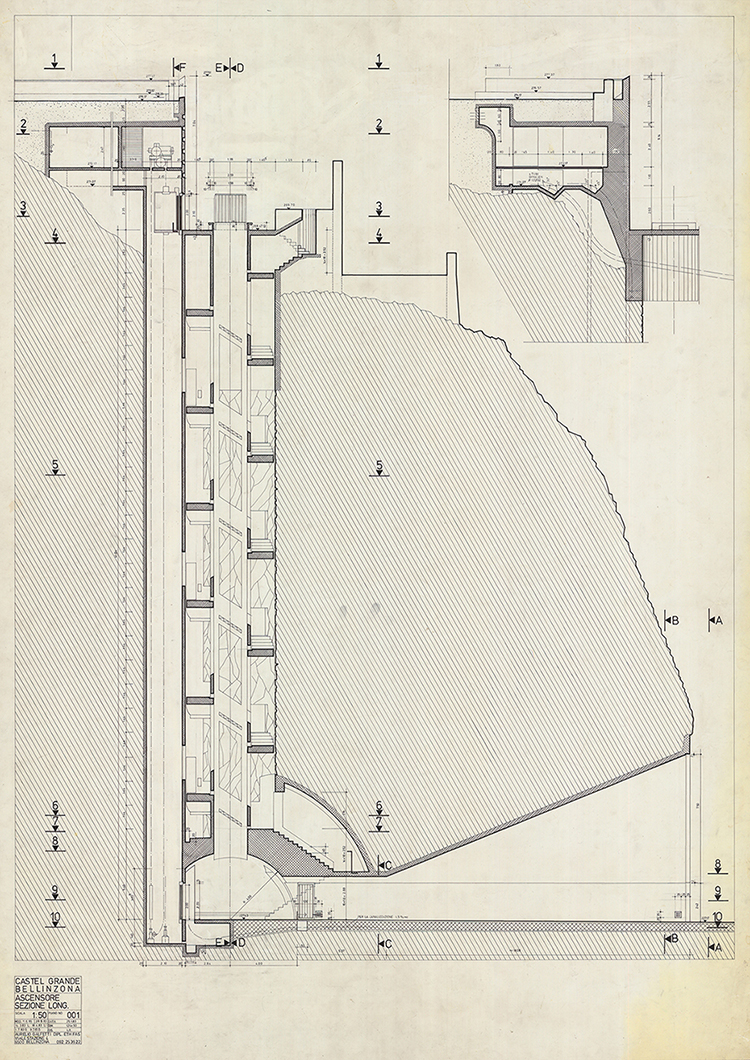

Among his completed works, his intervention at Castelgrande in Bellinzona stands out. One of the three castles surrounding the city and a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000, it was originally built in the 13th century and has undergone multiple expansions and restorations throughout its history. The most recent intervention, led by Aurelio Galfetti, balanced the themes of preservation and transformation as equal elements in heritage interventions.

Over an extended period (1981–1993), the intervention at Castelgrande enhanced the creation of accessible public space across the various slopes of the walls, with green planes integrating harmoniously with the striking surrounding landscape. This process established constructive and formal clarity through the redesign and the removal of scattered structures and vegetation juxtaposed against the walls. This transformation, which Galfetti described as “revealing by demolishing the dissonant,” introduced a new approach to heritage interpretation, providing a clearer and more perceptible understanding of the site through a process of selection and subtraction.

To support and justify this intention, Galfetti designed an imposing opening carved into the rock, allowing it to be reinterpreted to house a concrete lift and staircase. This intervention bridges a significant height difference, creating a mechanism of connection between the city and the castle.

In the creation of this public space, combined with Livio Vacchini’s intervention in designing the new Piazza del Sole, the city, the hill, and the castle were brought into a strong architectural and social relationship with the urban fabric.

This gesture of exposing the mountain’s interior, with its geological components, revealing the various layers of sedimentation and glacial erosion, can be seen as drawing a parallel with the infrastructural gesture of the Swimming Pools. One might infer that the unveiling of the rock layers, through the concrete access routes bridging approximately 50 metres of elevation difference, or the 300-metre-long concrete pathway at the Swimming Pools, both act as incentives for mobility. These elements, deeply embedded in the landscape, of a territorial nature, become creators of space and time.

Figure 7 – Castelgrande in Bellinzona (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

Figure 8 – Castelgrande de Bellinzona, Public Elevator Courtyard (Source: Archivio del Moderno).

Figure 9 – Castelgrande de Bellinzona, access to the public elevator (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

Figure 10 – Castelgrande de Bellinzona, access to the public elevator (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

Flora Ruchat-Roncati, born in Mendrisio, graduated from ETH Zurich in 1961. She continued her architectural journey through various partnerships, notably with Doef Schnebli, Tobias Ammann, and Renato Salvi. Having established herself as a prominent figure in Ticino architecture, Flora also became the first woman to hold a professorship at ETH Zurich, where she taught from 1985 to 2002, contributing to the education of several generations of architects. During her time in Rome, where she lived and established a studio, she became a consulting architect for the National Consortium of Housing Cooperatives.

Her academic career also extended to other universities, with notable appointments at the Università LUAV di Venezia and the Politecnico di Milano. In addition to her work as an architect and professor, she also contributed as a theorist and urban planner, further embracing a political dimension.

Following the dissolution of the Bedano studio, Flora and Ivo moved to Riva San Vitale, where they settled in a courtyard house, restored by Flora, called Corte dell’Inglese. This medieval building became the residence and studio for several artists and architects. Flora’s vision was to create an important communal space here, a place where Ivo Trümpy continues to work to this day.

Figure 11 – Loggia of Corte dell’Inglese in Riva San Vitale (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

Ivo Trümpy, born in Bellinzona, graduated from the Technical College of Lugano-Trevano. After his partnership with Galfetti and Flora, he formed a new partnership with Aurelio Bianchini, establishing a new studio in Riva San Vitale. He taught at SUPSI (Scuola Universitaria Professionale della Svizzera italiana). According to Nicola Navone [39], his contribution to the Swimming Pools project was certainly crucial during the execution and construction phases. Ivo Trümpy later mentioned, after a visit to his studio, that the project oversight was intense and often daily, requiring continuous drawing work and detailing to keep up with the rapid pace of construction and resolve all possible details.

Reflecting on the years they worked together in Bedano, the three of them fondly recall, in various publications, a time of great camaraderie and dedication to the profession, strongly influenced by Le Corbusier. Aurelio Galfetti recalls that the three of them “shared a collaboration born from a deep passion for architecture and admiration for a great master, Le Corbusier, our only master.” [40]

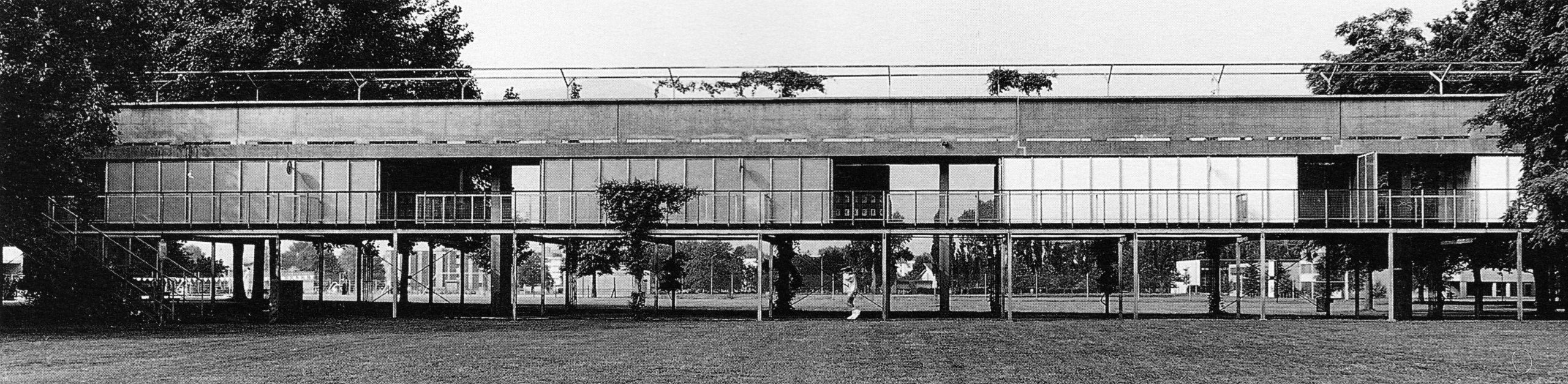

Regarding the built works, the school in Riva San Vitale, a small municipality in Ticino, holds a position of significance as an educational facility, designed and constructed in two phases (1962 and 1974). It exemplifies the aforementioned admiration for Le Corbusier, as well as the architects’ concern with resolving urban issues when designing a facility for a small village located on the shores of Lake Melano. The building, like the Swimming Pools, is listed in the inventory of protected cultural assets at the cantonal level.

As Martin Steinmann notes in his article La Scuola ticinese all’uscita dalla scuola, published in the previously mentioned monograph [41], the school reflects the social role assumed by architecture, also conveying a certain political commitment. He further mentions that numerous parallels can be drawn between the project’s assumptions and urban codes, such as streets, crossings, and visual connections, emphasising that the experience of the city is central to the creation of spatial meaning. [42]

Figure 12 – Riva San Vitale Primary School, general exterior view (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

Figure 13 – Riva San Vitale Primary School, longitudinal section view (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

Currently well restored and in active use, the school reflects Corbusian influences, as elucidated by Aurelio Galfetti, such as the proposals for collective housing in Oued Ouchaia, Algiers, and the balconies in the Frugès neighbourhood in Pessac [43]. Galfetti emphasises that “Le Corbusier was, of course, at the centre of our interests, although our discussions often included references to other architects.” [44]. He adds that they avidly browsed the magazine Werk and the French L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, more than Italian magazines. Additionally, each of them would bring books and new publications, which were later followed by long discussions, while the drawing process flowed, often continuously being redrawn. [45]

For those who visit it today, the school transcends novelty in the way its layout stitches together the urban fabric of the small village, in an enlightening freedom, without revealing its construction in multiple phases. Free from barriers, the various volumes of the building dissolve into the site, offering intense circulation and a continuous relationship with its territory. The stairways, passages, and balconies, through which the children move, project the village and its topography, as if the visual relationship were as important as mobility itself.

Regarding the classrooms, Ivo Trümpy mentions: “They are quite generous, larger than what was typical at the time, with windows on all four sides to ensure good natural lighting and ventilation. The view is open to the village to the north, to the countryside to the south, and to the mountain peaks to the east and west.” [46] And then there is the exposed concrete, the solid brick walls plastered and painted in Corbusian blue, yellow-ochre, characteristic of the Ticino region, blending with the mountains.

Figure 14 – Riva San Vitale Primary School, general exterior view (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

4. Competition | Design | Built Work

4.1 Competition

The city of Bellinzona, the capital of the Canton of Ticino, was experiencing rapid urban growth at the time of the competition. Historically, it is characterised as a borderland, defined by the Ticino River, at the meeting point of three majestic valleys: Leventina, Blenio, and Mesolcina. Adding to its frontier character, shaped by its geographical location, stand three medieval castles on the Magadino plain: Sasso Corbaro, Montebello, and the above-mentioned Castelgrande, which have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 2000.

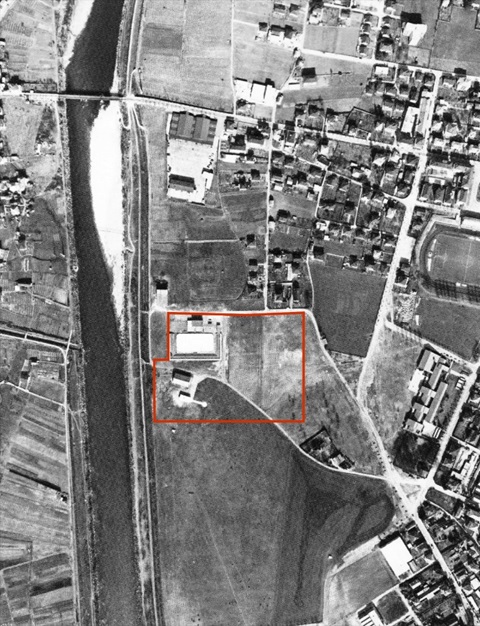

The competition for the swimming pools, launched by the municipality of Bellinzona on 31 March 1967, invited the design of a new public complex on a municipally owned site earmarked for expansion. The intervention area, covering approximately 27,000.00 m² and situated near existing or planned sports and educational facilities, incorporated a pre-existing skating rink, which was to be adapted as part of the competition programme. The planned expansion area for future facilities, adjacent to the competition boundary, left room for further reflection on the prospects for the growth of Bellinzona’s urban fabric.

Figure 15 – Aerial photograph before the construction of the Pools, with indication of the intervention boundary, Bellinzona (Source: Monografia Il Bagno di Bellinzona by Aurelio Galfetti, Flora Ruchat-Roncati, Ivo Trümpy, boundary marking by the author).

The programme includes the design of three swimming pools: an Olympic-sized pool, accompanied by a smaller pool nearby but separate, equipped with two diving boards and two platforms; a heated pool for instructional purposes, measuring 25 x 21 metres; and a children’s pool connected to recreational areas. The skating rink, previously mentioned for adaptation, is to be converted into a non-swimmers’ pool during the summer.

The programme also requires consideration of changing rooms, ticket offices, technical and service areas to accommodate a daily capacity of 3,000 people. A self-service restaurant for approximately 300 patrons must also be included. The competition is open to architects registered with the Ticinese Order of Engineers and Architects, residing within the canton or nearby regions.

The intervention area is defined to the northwest by an embankment constructed in the early 20th century as part of the major flood protection drainage works known as the Magadino Plan. This construction enabled the creation of a vast plain, 2.5 metres above the water level, evoking the image of an extensive natural floodplain, providing the city with a significant recreational space.

At this northwestern boundary, marked by the embankment, the construction of a motorway is planned, which competition proposals must take into account. Similarly, on the southeastern boundary, the continuation of the existing road access is foreseen, with the extension of the Mirasole Road already planned. The competition programme stipulates that the entrance to the swimming pools must be located along this planned road access.

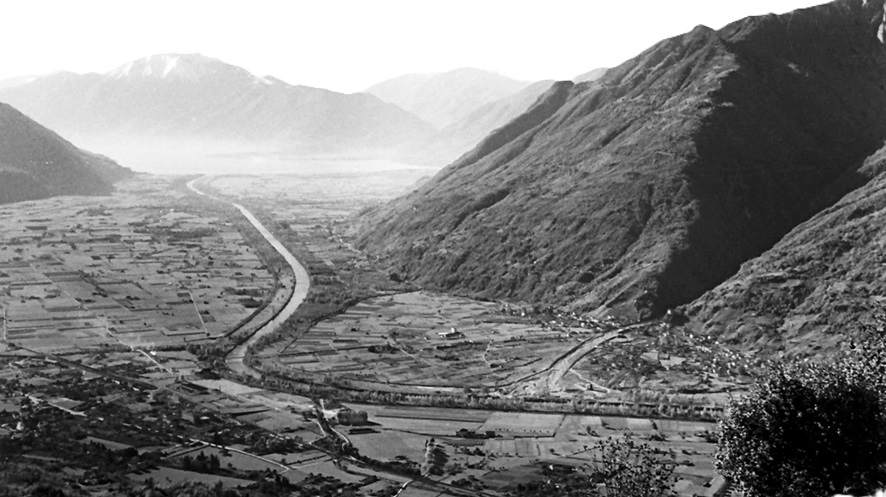

Figure 16 – View of the Magadino plain, Bellinzona (Source: Storia – Consorzio Correzione Fiume Ticino (ccfticino.ch)).

Adjacent to the southeastern boundary of the competition area lies a significant educational facility known as the Cantonal Gymnasium, constructed between 1956 and 1958 by architects Alberto Camenzind [47] and Bruno Brocchi [48]. Influenced in both materiality and volumetry by educational buildings in Northern Europe, the school is organised around a sequence of small garden courtyards and has recently been restored.

The entire competition process – from the architects invited to submit proposals, to the registered participants, and the analysis of the various submissions – is thoroughly documented in the seminal monograph Il Bagno di Bellinzona by Aurelio Galfetti, Flora Ruchat-Roncati, and Ivo Trümpy, edited by Nicola Navone and Bruno Reichlin. In addition to the competition winners, notable entries that secured second, third, fourth, and fifth places were submitted by Francesco van Kuyk, Dolf Schnebli, Peppo Brivio, and Mario Campi, respectively.

As for the jury, we list all the participants due to their significance in asserting the winning proposal: the president of the Bellinzona trade union, Sergio Mordasini; the president of the company Bagno Pubblico SA, Fermo Patocchi; and the architects Tita Carloni and Luigi Snozzi (members of the Cantonal Commission for Historical Monuments and, since 1962, involved in the development of the Safeguard Plan for the Historic Centre of Bellinzona), who were 36 and 35 years old, respectively, at the time of the competition. Joining these architects was Sergio Pagnamenta, older and with substantial professional experience. Also involved in the team responsible for drafting the previously mentioned Safeguard Plan was the architect Livio Vacchini, although he was not a member of the jury for the swimming pool competition.

The submission of competition proposals took place on 31 August 1967, with the delivery of a scale model at 1:500 on the following day. It is important to highlight the time frame allocated for the development of this significant facility for the region: five months. This period is lengthy compared to the reality of contemporary public competitions, a circumstance often referred to by Galfetti as essential for a thorough and well-considered development of the programme and its integration into the site.

Nicola Navone explains in the aforementioned monograph that Carloni, Snozzi, and Vacchini, within the Safeguard Plan, conducted an in-depth survey of the historic centre in order to propose a strategy for connecting the monuments with the city fabric. Alongside this, they designed “a network of public pedestrian connections along the course of the walls themselves, sometimes on the pathways, sometimes at the foot of the wall, ensuring a unique route.” [49]. This intervention enabled the proposal of a “possibility for visiting, in addition to the castles, the towers scattered along the defensive wall.” [50]

It is within this context—of a vital sports programme for the city, in a historic location reflecting on its preservation, while simultaneously experiencing significant urban expansion, and supported by a knowledgeable and well-prepared jury—that the selection of the winning proposal is framed. While all other proposals focus on the northeastern and northwestern boundaries, either more organically or more rationally, constrained by access points and integrating the existing fabric while anticipating future programmatic premises, the winning proposal by Aurelio Galfetti, Flora Ruchat-Roncati, and Ivo Trümpy provides a response that is not just correct, but also demonstrates the urgency of thinking about how to intervene in the city and how to reflect on the territory.

For the winning team, this particular site, with its vigorous topography, characteristic of a region marked by infrastructural constructions capable of dealing with extreme altitudes and deep valleys, becomes the revealing force of the proposal. By extending beyond the intervention boundary, it recognises that the scale should be territorial.

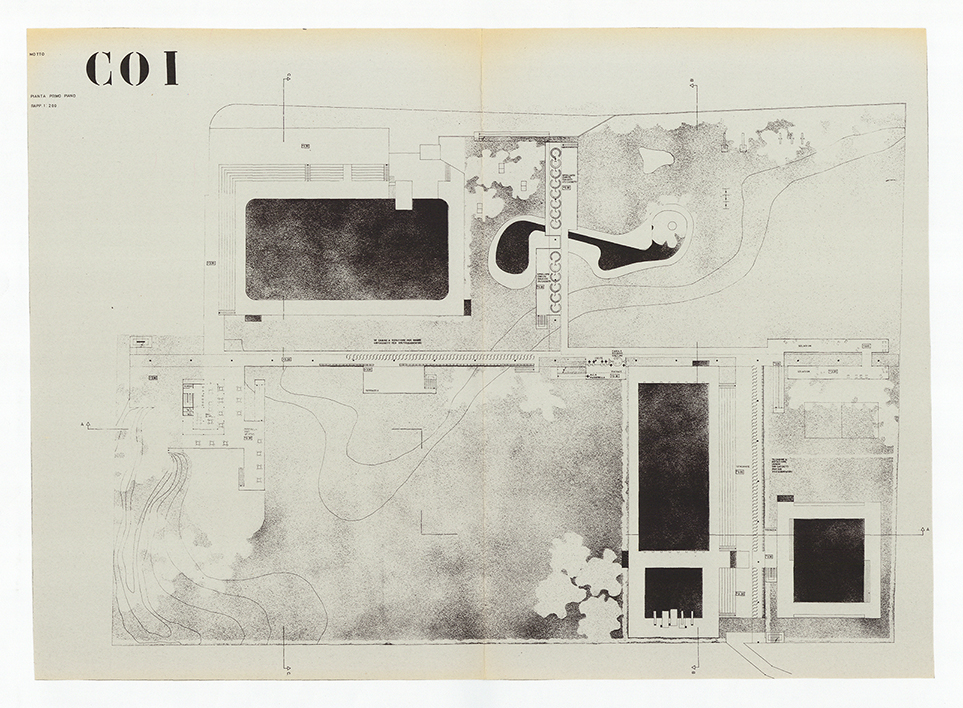

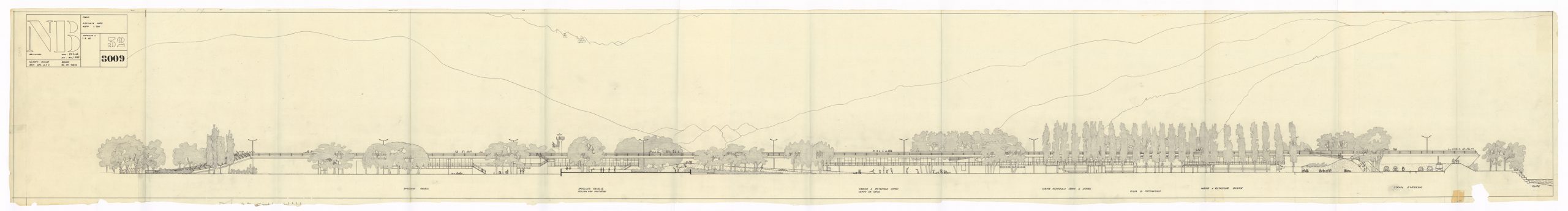

The architects distinguish themselves by proposing a walkway placed in the centre of the intervention area, orthogonal to the Ticino River, with two perpendicular arms extending from the crossing, raised six metres above the plain level. They present the proposal with two implementation solutions: one within the intervention boundary and the other extending beyond it, in an attempt to demonstrate that the strength of the solution lies in the extension of its gesture, achieving an urban connection. The walkway, by elevating itself, allows the ground plane to be freed for the placement of the various pools, articulated in a formal freedom. Three metres above ground, beneath the walkway, the programme is located, merging form and function.

Figure 17 – Partial Hypsometry, Bellinzona, Canton of Ticino (Source: www.mapbox.com).

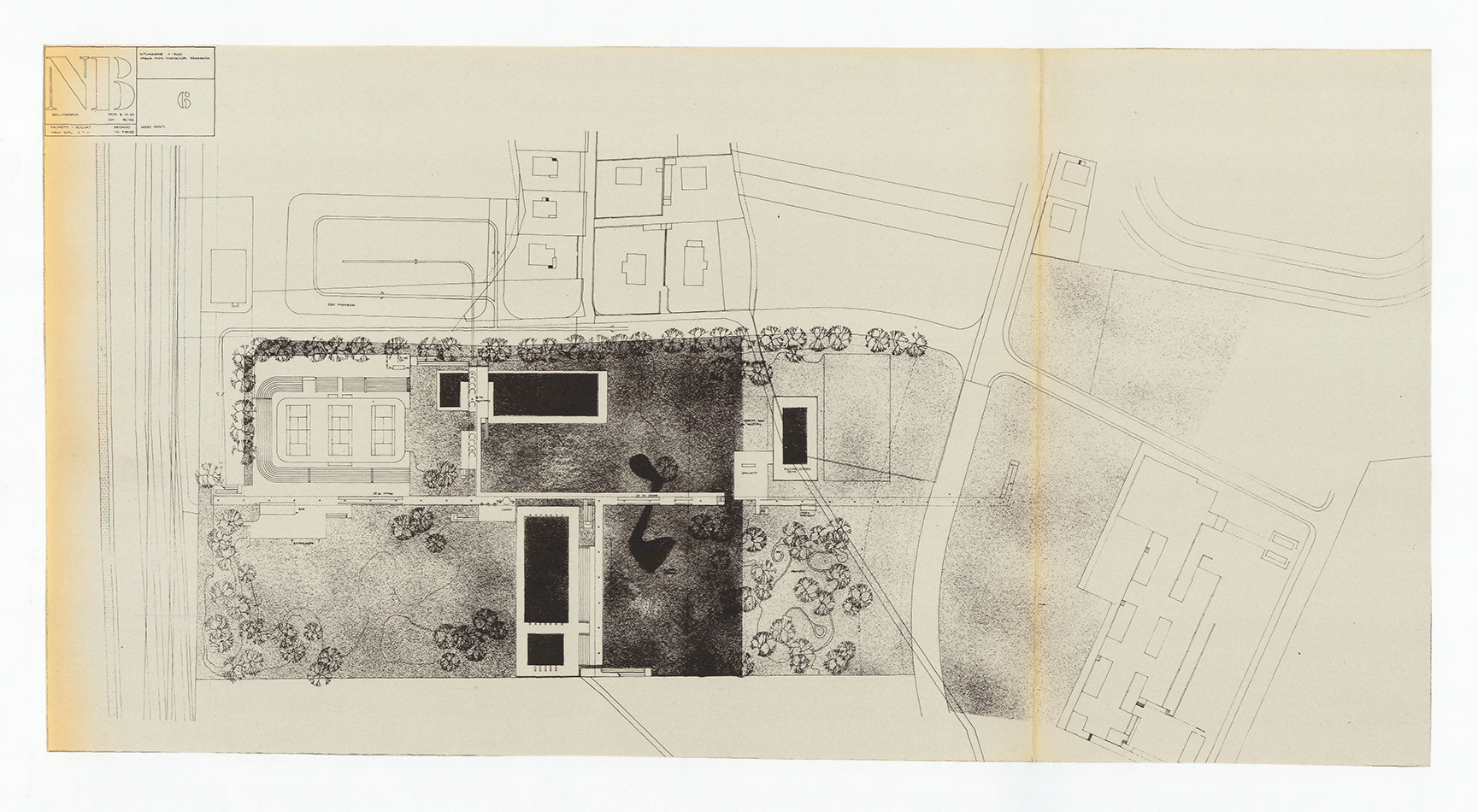

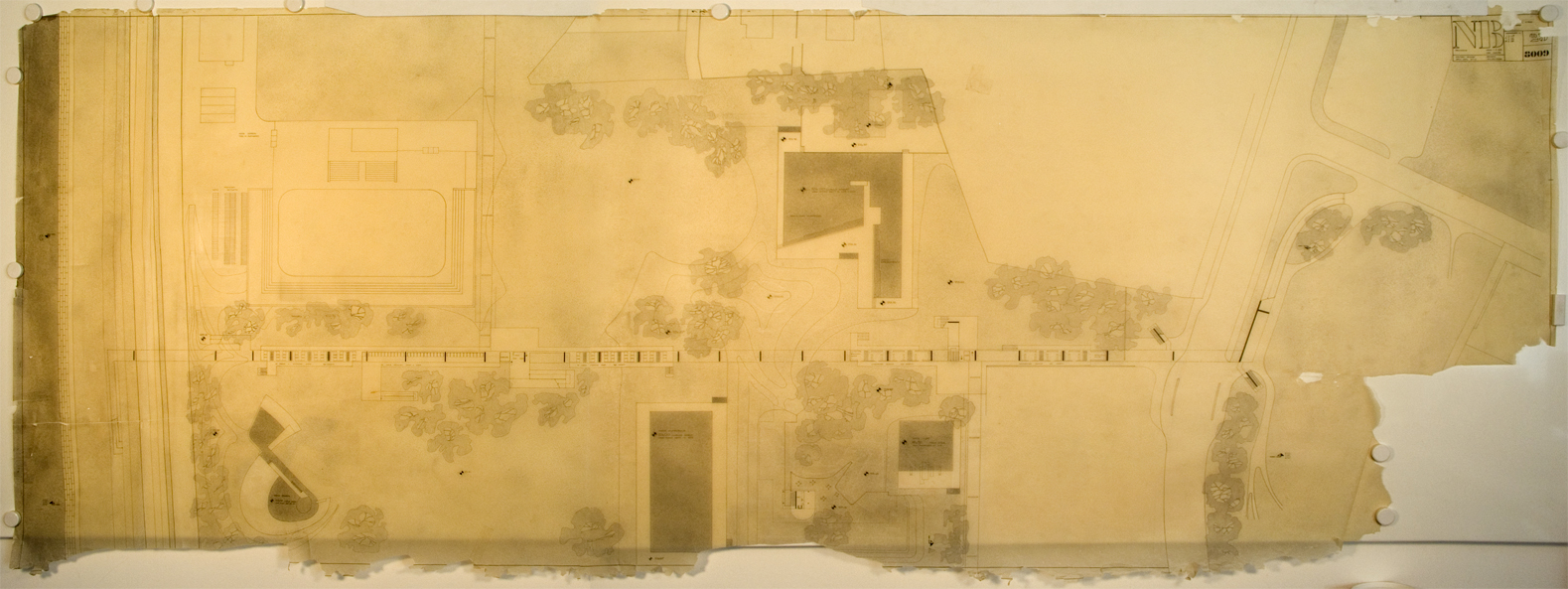

Figure 18 – Panel of the competition proposal, general plan, August 1967 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AFR T 19/2).

The panels of the winning proposal revealed ingenuity, boldness, and urban acuity, outlining a solution that, to be fully realised, must surpass the boundaries established by the competition programme. The project evokes, at multiple scales and through various graphic registers—both rigorous and free-perspective drawings—the search for the site’s identity, aligning itself with the relentless idea of evoking mobility. It seeks to liberate the artificial plain, as though not questioning a right already attained, one that is hard to imagine being constrained after such a sovereign engineering achievement.

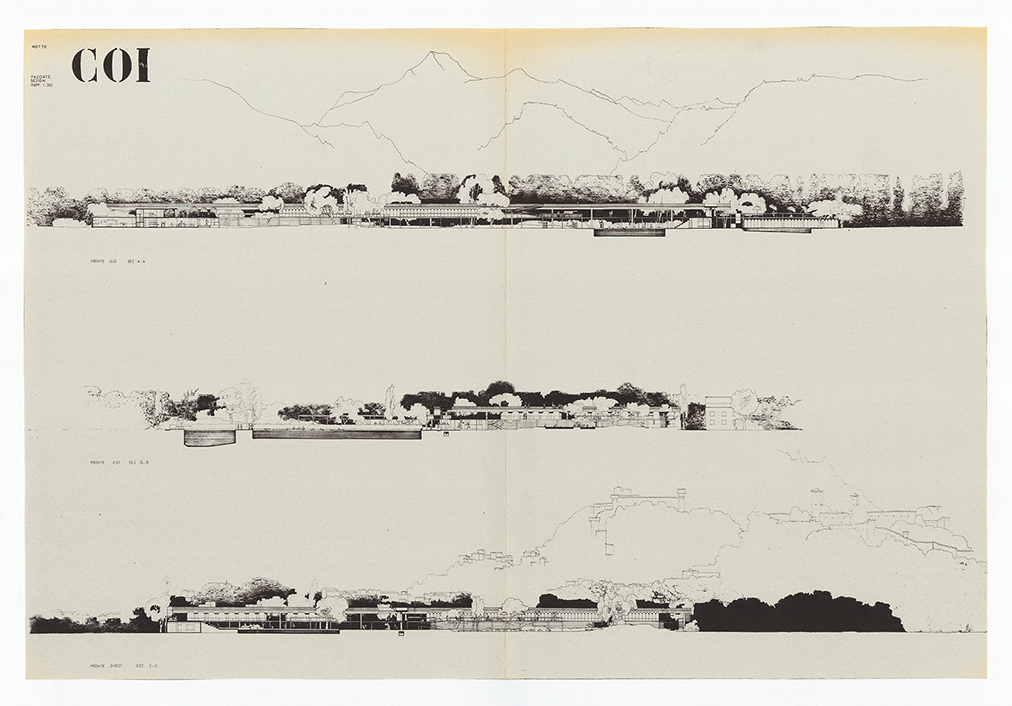

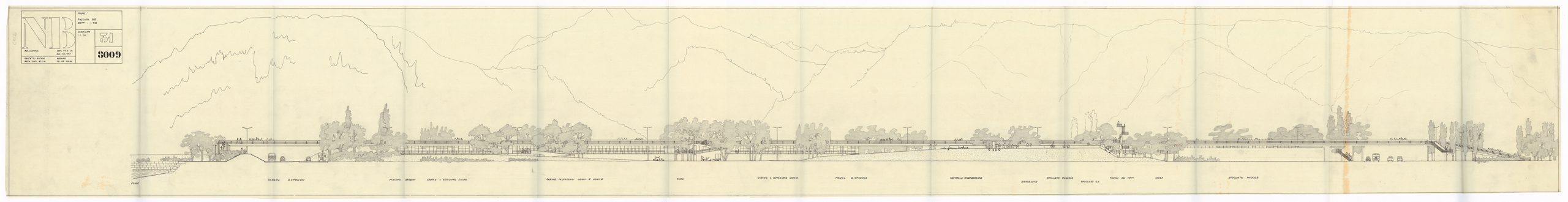

The proposal suggests, in the sketches, the idea of establishing a visual connection with the topography, its castles, and its walls. In contrast to the formality of the legal requirements for the pools, it sketches a suggestive interpretation of river bathing, by placing, beneath one of the arms of the walkway, an organic form for the children’s pool, subtly creating a concavity in the plain. The proposed landscaping remains formal and statically planted, demarcating access paths or creating dense groves in very specific locations. However, in the longitudinal sections, it is essential to consider the desired density and stature of this landscaping, which will take time to become consistent within the landscape and its territory.

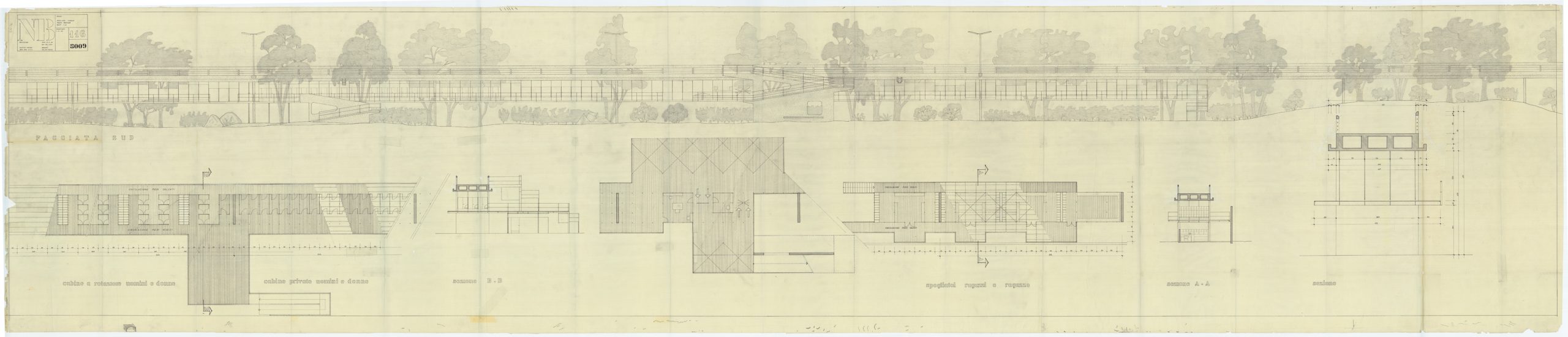

Figure 19 – Panel of the competition proposal, elevations, August 1967 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AFR T 19/3).

Figure 20 – Panel of the competition proposal, walkway schemes, August 1967 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AFR T 19/3).

It is essential to highlight the courage and discernment of the jury, which, recognising the relevance of the solution, chose a more costly proposal that required public consultation to enable the use of land identified as future expansion, not intended for this initial phase of municipal investment. The jury’s decision stands out for selecting a proposal that resolves future obstacles by allowing large flows to be directed to distinct areas, invoking the organicity of urban movements. According to Nicola Navone, in the jury’s report, it can be read that “each starting point will lead to the correct destination,” adding that the jury recognises the proposal’s validity as “a fundamental contribution to current architectural thought,” “a fragment of urban organisation, composed of circulation, structures, and specialised furniture (bathing equipment) above the entirely respected natural space,” and “an authentically new installation of assured interest.” [51]

Bruno Reichlin mentions, in his article in the monograph, the references highlighted by the architects in presenting their proposal, such as the Pont du Gard, but also the more familiar images of the Lavertezzo bridge in the Verzasca Valley, a destination for river bathing during the architects’ summer holidays in their adolescence. He notes “a strong image that perfectly encapsulates the concept of the Pools: a public path anchored in the territory, solidly constructed to endure over time and offer a vantage point from which one can contemplate the magnificent landscape, both near and distant.” [52] He concludes that the project “sits at the confluence of some of the most interesting lines of post-war architectural thought and expresses them with commendable clarity. Rarely has territorial culture, urban planning, and architectural thinking been embodied in a built project in the post-war period: let us not forget that, in fact, the most interesting and radical urban proposals by the architects of Team X remained on paper. An irreplaceable work, unique in its genre, the Bellinzona Pools undoubtedly deserve a prominent place in the 20th-century global architectural heritage.” [53]

Where most see little more than the territorial proposals of Le Corbusier for Algiers[54] or Rio de Janeiro [55], the infrastructural gestures of Chandigarh [56], or the aforementioned streets-in-the-air by Alison and Peter Smithson, these comparisons, when supported, do not reduce the proposal but perhaps consolidate it, adjusting its construction to the scale of the site, evoking its reminiscences and the search for cultural meaning in the landscape. In an infrastructural impulse, the proposal expresses the premises of a public facility, resolving, in a dual gesture of continuity and radicality, the territorial connection between the valley, Bellinzona, and the Ticino River.

Figure 21 – Photograph of the competition proposal model, 1967 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AFGdP).

Figure 22 – Photograph of the competition proposal model with Schemes for the expansion of the walkway, 1967 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AFR).

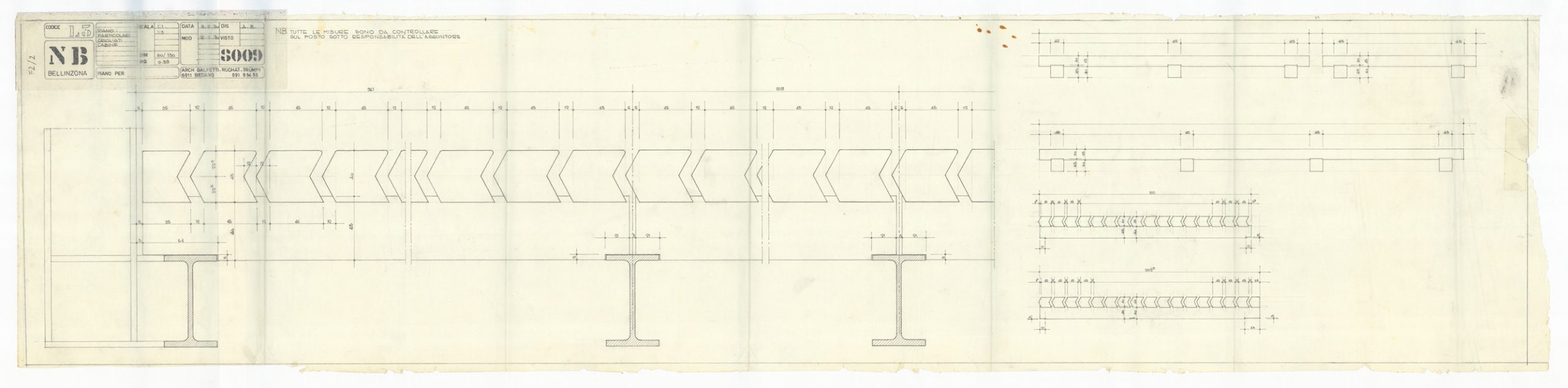

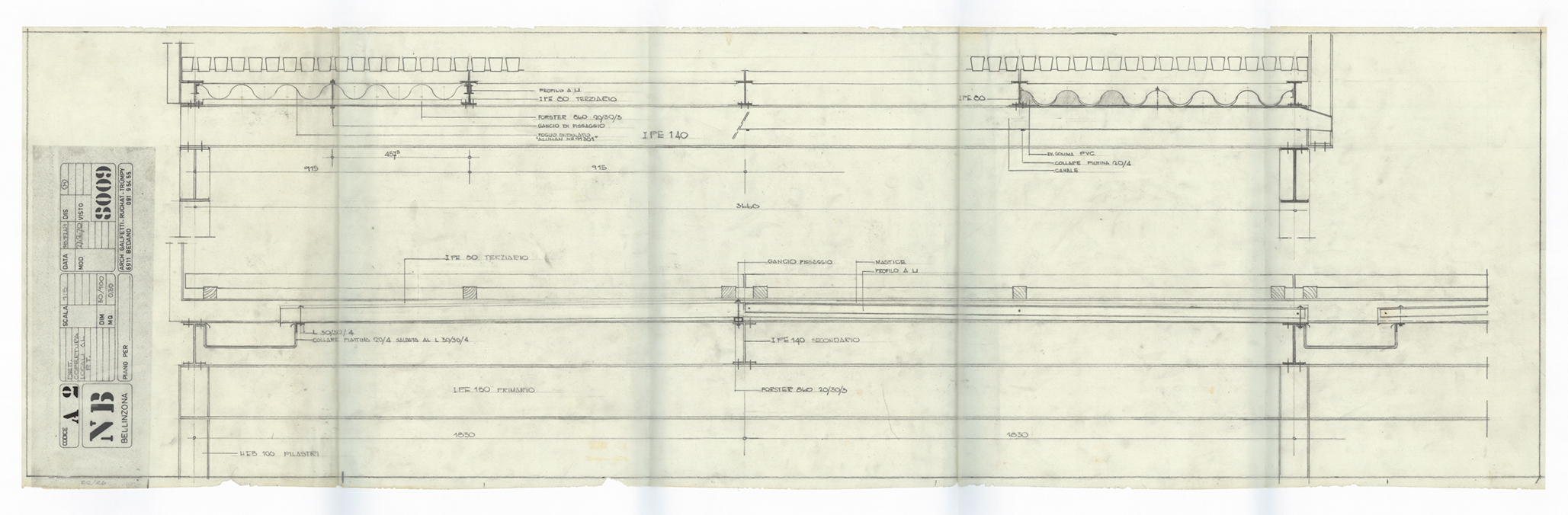

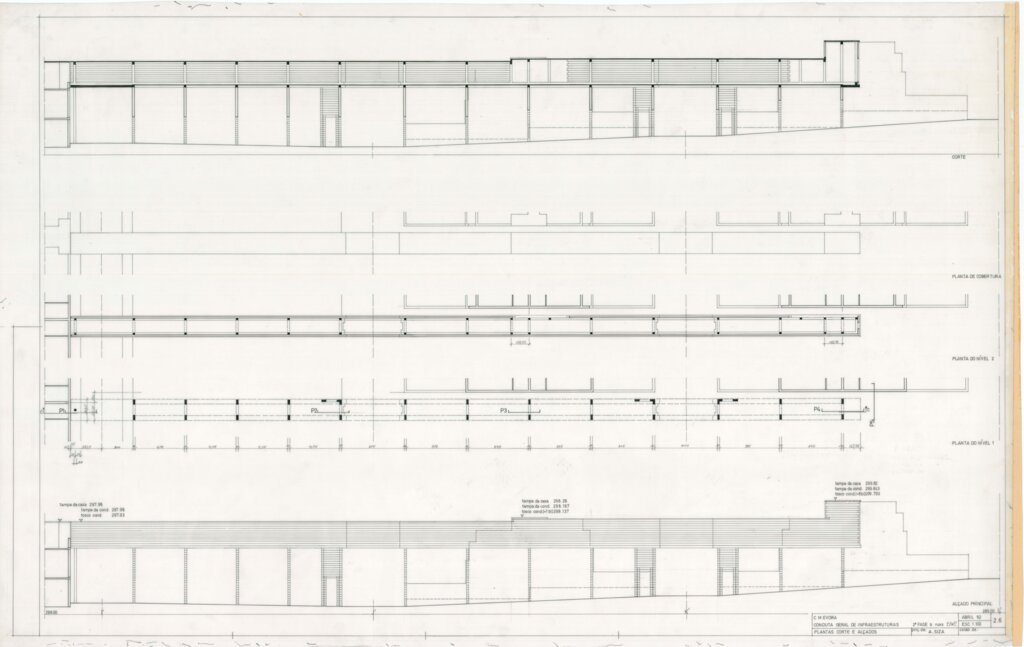

4.2 Design

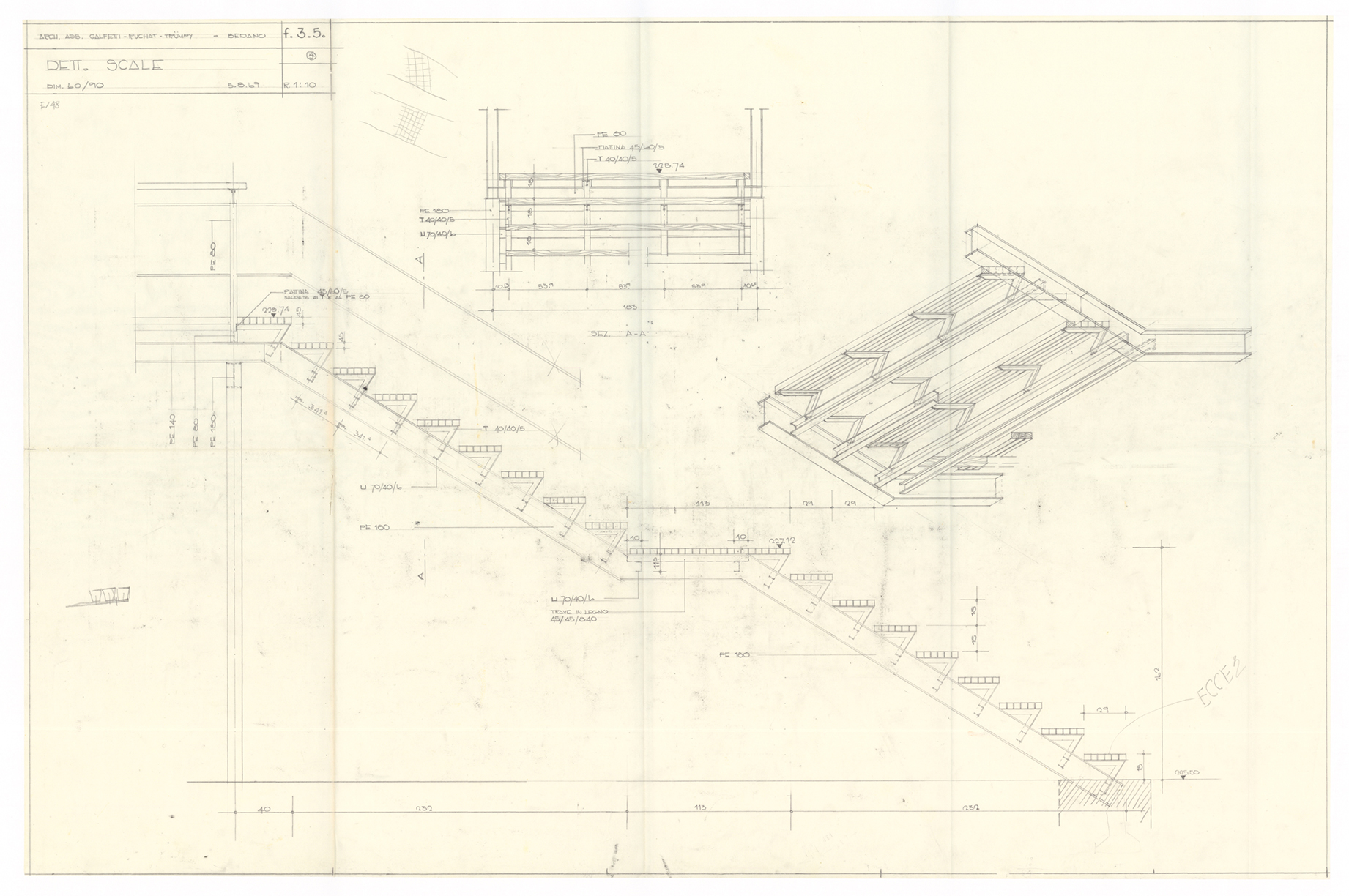

The archives of architects and engineers donated to the Archivio del Moderno are extensive, insightful, and captivating in their revelation of the evident intensity, commitment, and dedication of the entire team. This donation has enabled the recent publication of the previously mentioned monograph, Il Bagno di Bellinzona, as well as shed light on the entire execution process, potentially contributing to the effective preservation of this architectural exemplar. Included are several representative drawings from various stages of execution, exemplifying the exhaustive work referenced, which have also been donated to the Archivio del Moderno.

Figure 23 – General plan, proposal for the extension of the walkway, November 1967 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AFR).

Figure 24 – South elevation, March 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Def T 10/1).

Figure 25 – North elevation, March 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Def T 10/2).

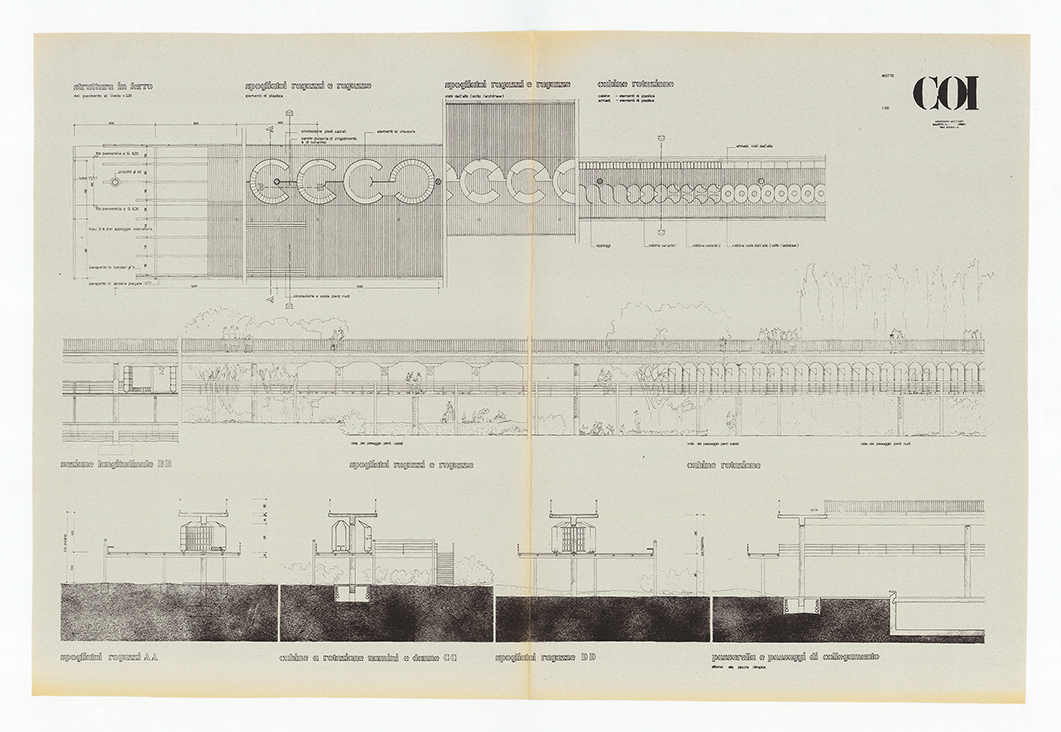

Figure 26 – Elevation, plans and sections of changing rooms and cabins, February 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Def T 15/1).

Figure 27 – General Plan, proposal, January 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21).

Figure 28 – General Plan, proposal, April 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21).

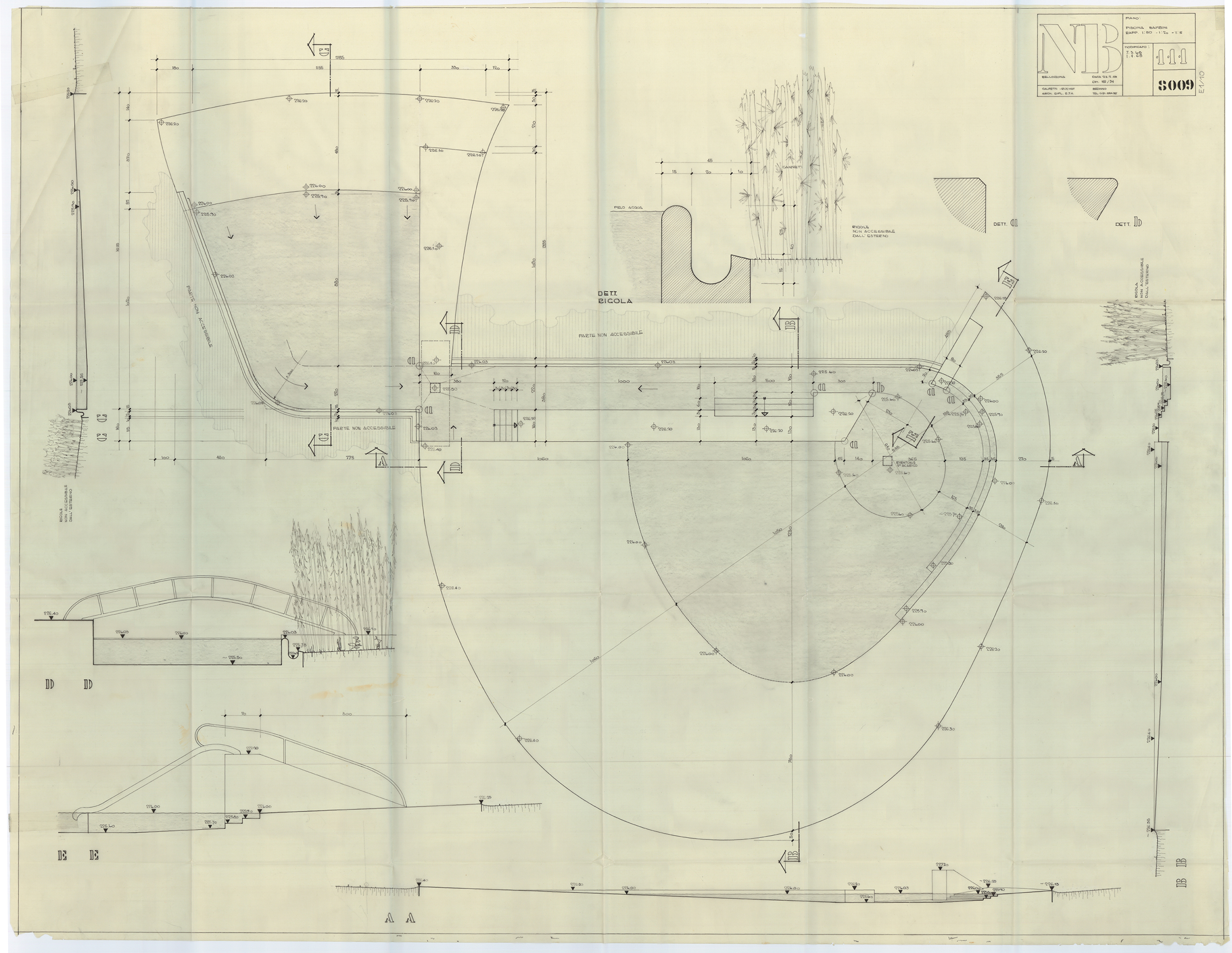

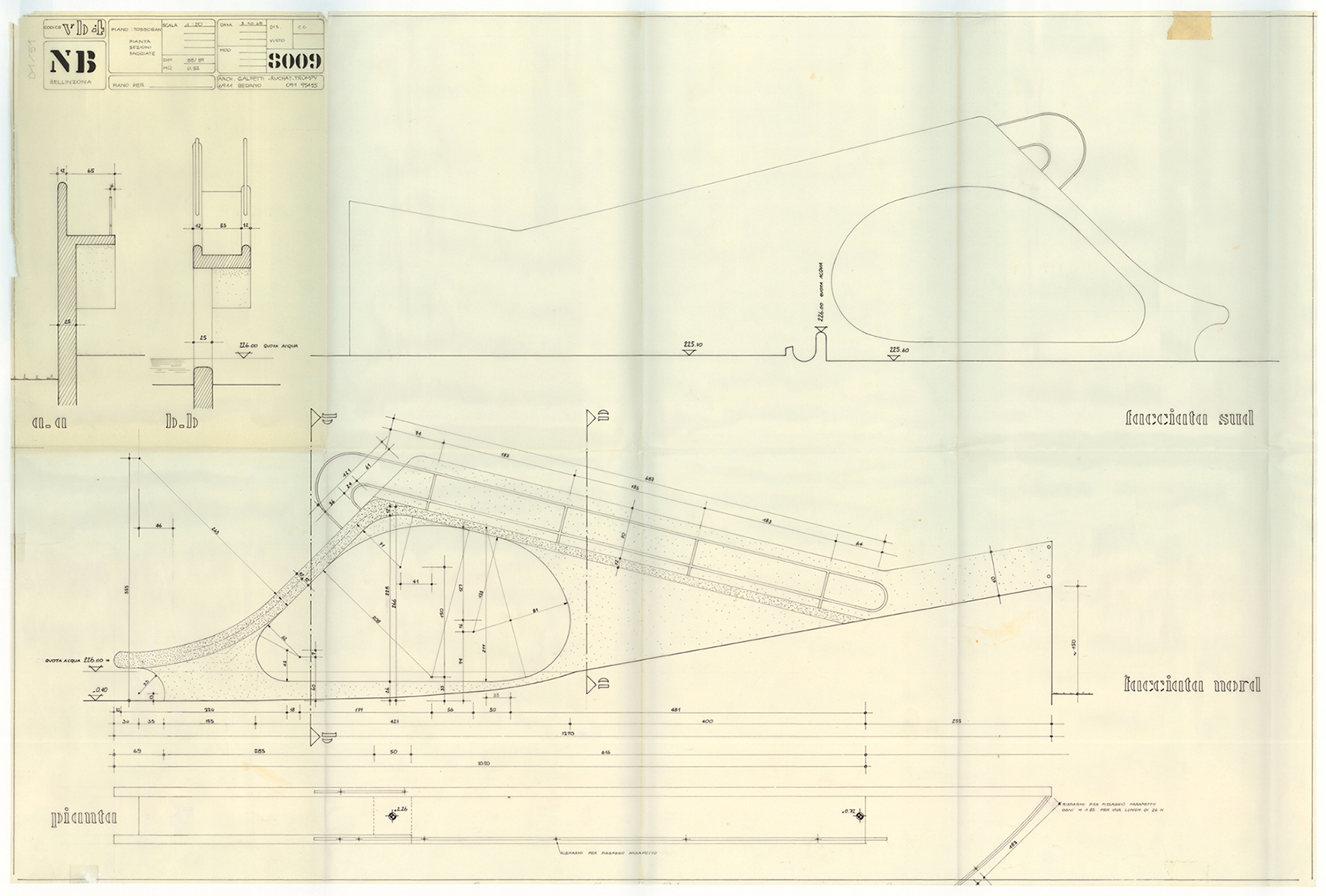

Figure 29 – Plan, sections and details of the children’s pool, February 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Def T 13/1).

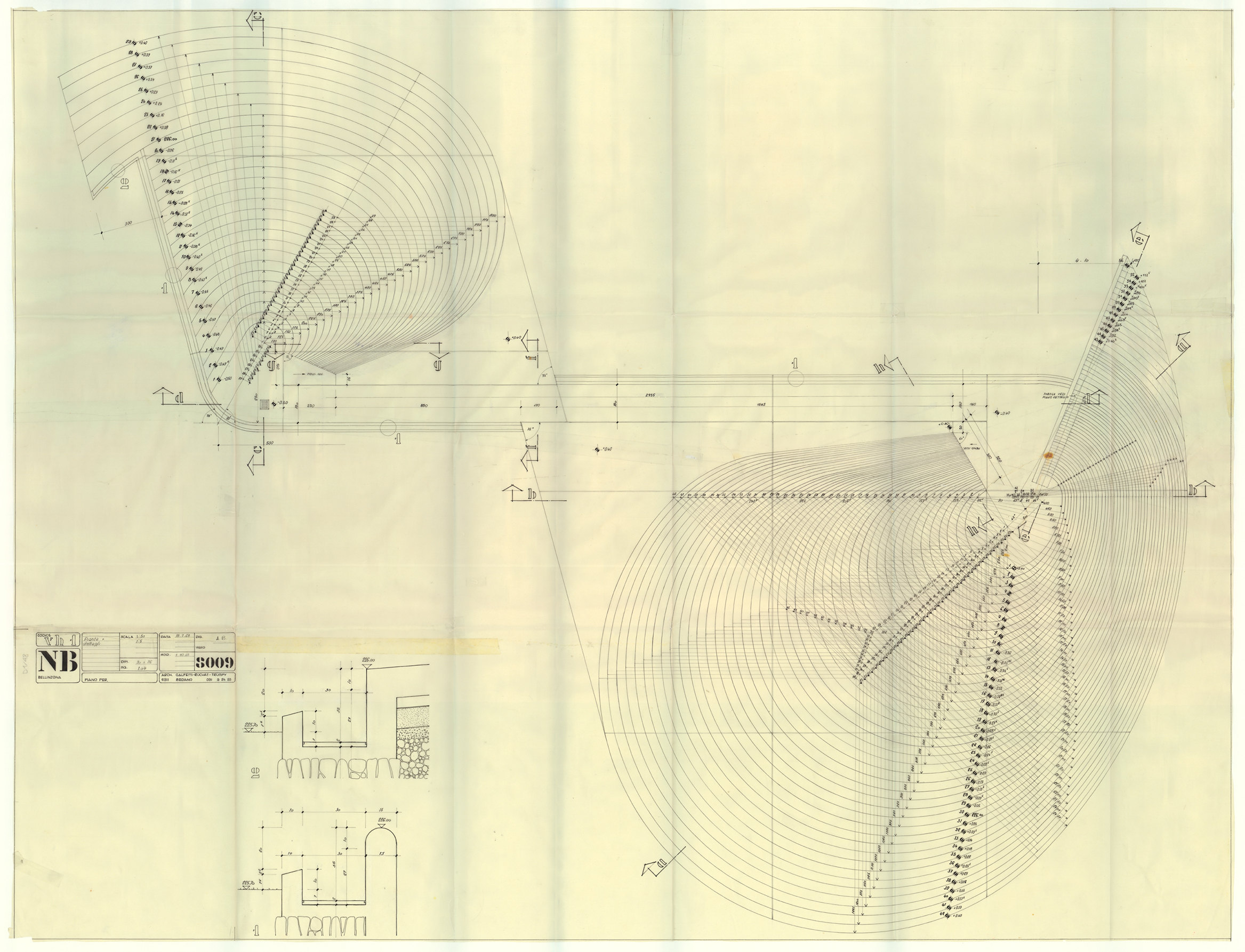

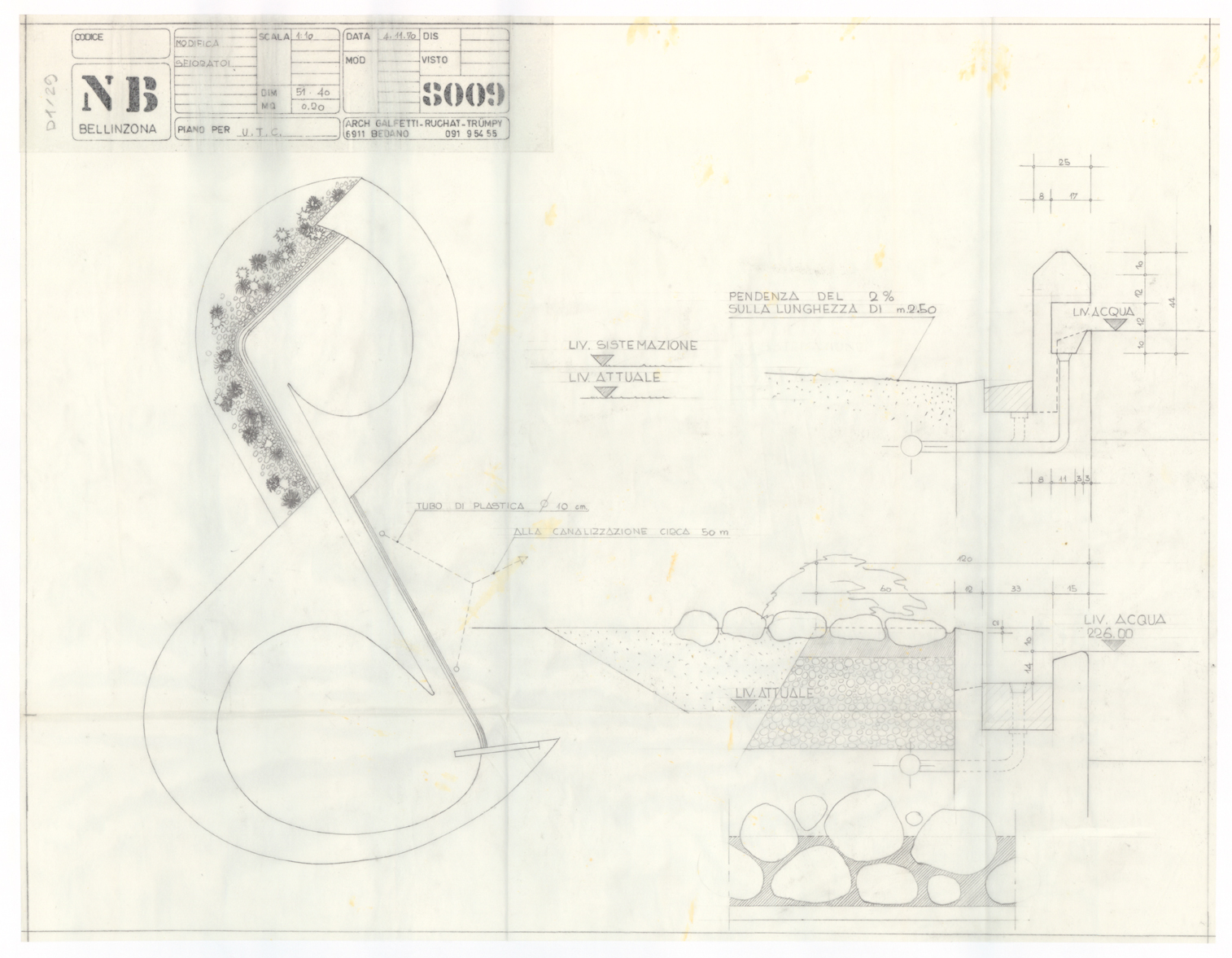

Figure 30 – Plan of the children’s pool indicating the layout, February 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es T 40/3).

Figure 31 – Plan, sections and side elevation of the children’s pool slide, October 1968 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es C 4/27).

Figure 32 – Details of children’s pool, November 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti).

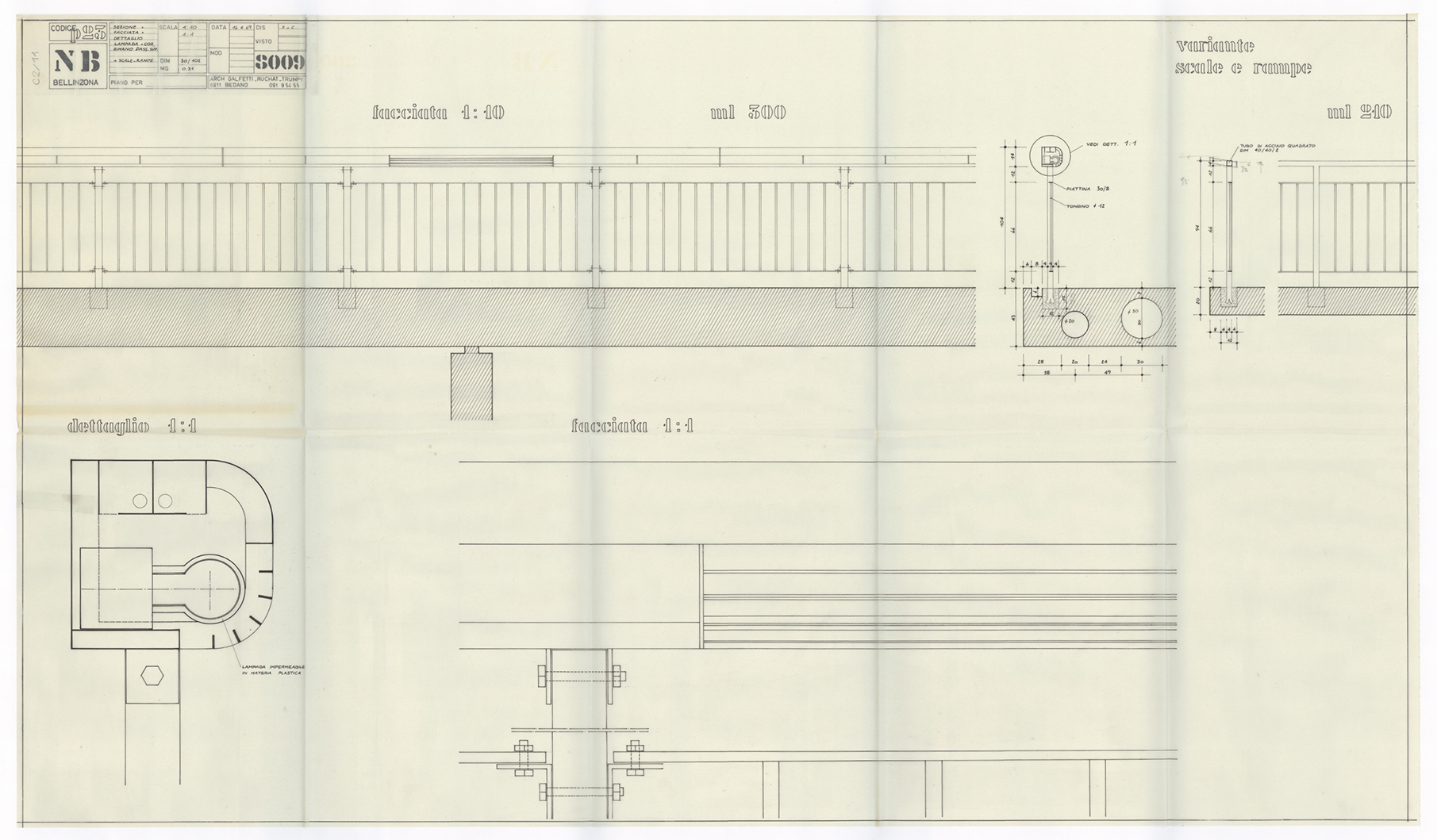

Figure 33 – Detail of the handrail of the walkway, April 1969 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es C 2/6).

Figure 34 – Variant of the parapet, January 1969 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, LG 21 Es C 2/12).

Figure 35 – Detail of the handrail of the walkaway, February 1969 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es C 2/3).

Figure 36 – Detail of the Pergola,1969 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es C 2/10).

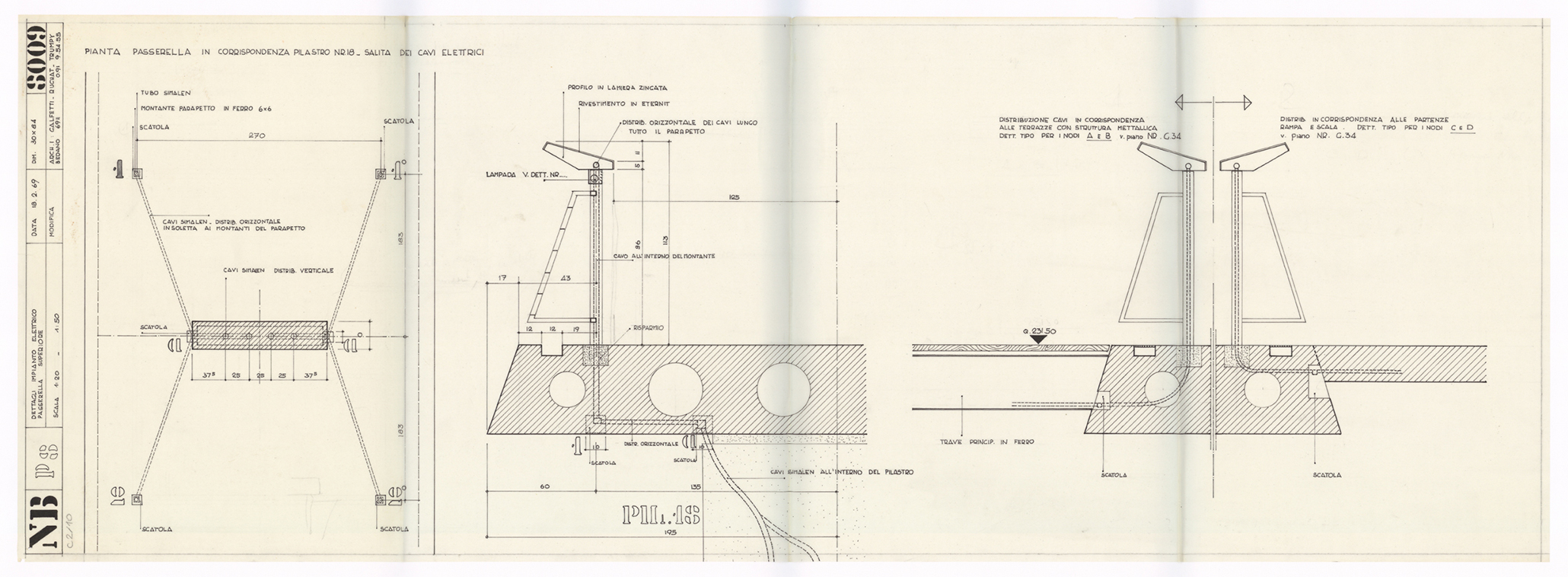

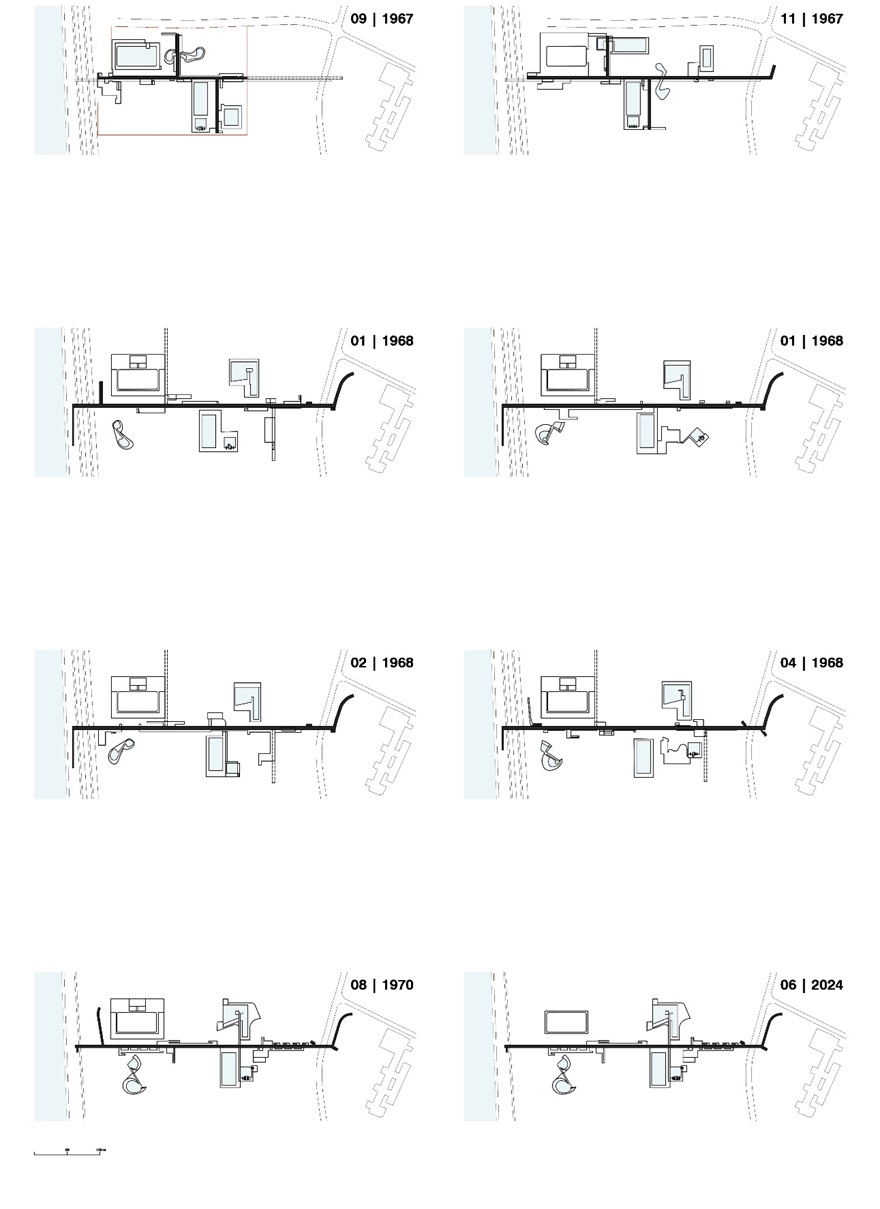

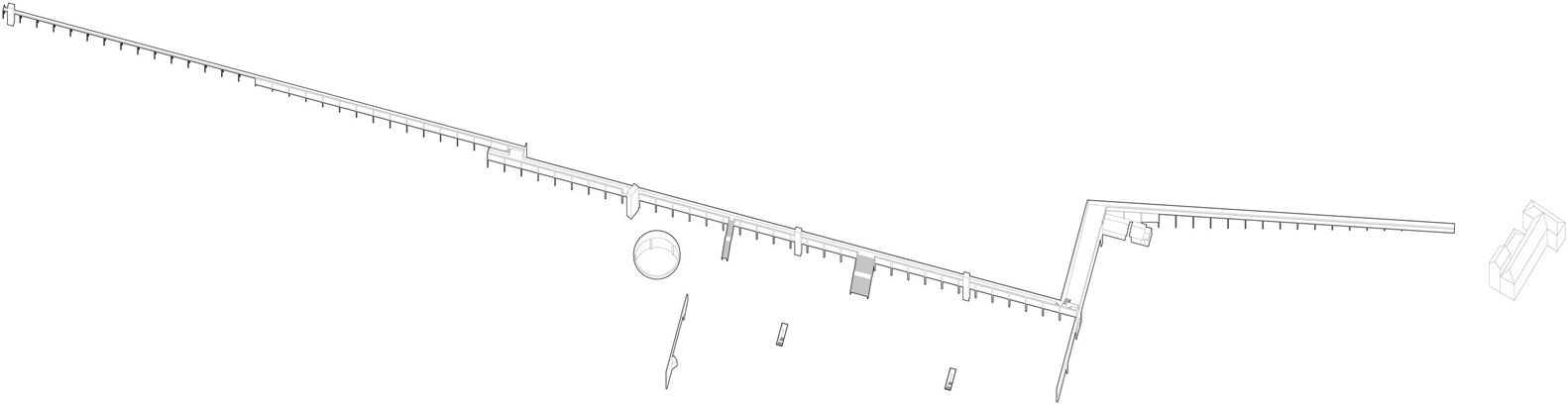

To better explain the evolution, hesitations, and constant alterations to the project—namely regarding the walkway, its access points, and the placement of the pools along with the corresponding intermediate programme—several summary plans are now being redrawn. This aims to facilitate a more synthesised and clearer comparison of the proposal’s development.

Figure 37 – Summary Plans of the proposals developed between September 1967 and August 1970, including a graphic representation of the current situation (Source: Drawings by the author, based on plans from the Archivio del Moderno, 2024).

Following the public presentation of the winning proposal (09/1967), the team began sketching the extension of the walkway (11/1967), confronting a revision to one of the initial competition programme premises. This revision proved both costly and complex to implement, particularly in adapting the skating rink into a summer pool. Another modification, stemming from the jury’s critique, concerned the entryway connecting the site to the city. The entryway was deemed too narrow and required replacement with a ramp.

The changing rooms, originally conceived in the competition project as prefabricated plastic elements functioning as rotational cabins, were arranged in a linear configuration, forming an extensive filter. However, larger circular cabins serving schools lost this almost metabolic configuration, instead gaining spatial substance through their form, light, and constructive detailing.

It is evident that the various studies developed exhibited great intensity and strength in architectural design. This tendency to frequently challenge and revise already completed work is often highlighted by the architects themselves, reflecting their courage in the constant act of redrawing and improving.

The positioning of the pools underwent several adjustments as a result of refinements to the dimensions and structural solution of the walkway. The concept of water flowing beneath the footbridge, highly desired by the architects, emerged as a non-negotiable solution, evoking a shared memory of adolescence and river bathing. In this context, the children’s pool, organically designed, shifted position in a kind of spatial dance across various proposed plans.

However, this solution proved technically challenging and costly, coming into conflict with the structural columns of the walkway and the intermediate floor. The final decision was to separate the children’s pool and place it closer to the embankment to be defined near the dyke and the river, using earth excavated from the pool construction to shape the terrain.

The project needed to be redesigned to address unauthorised economic excesses. As often happens, such constraints allowed the design to reach its essence. The perpendicular arms of the central walkway were removed (01/1968), now being identified as elements that could potentially be built in a future expansion. The separate platforms for the restaurant and its terrace, as well as the planned earthworks for this solution, were not approved. Instead, this area was incorporated into the direct connection with the walkway at the intermediate level.

The diving pool, which had also been tested as a separate feature from the Olympic pool (04/1968), was brought back into proximity, freeing up grassy space and optimising resources.

The project overcame numerous challenges, impasses, and budgetary restrictions. The greatest obstacle arose in a municipal referendum held to validate the expansion of the intervention area. Galfetti noted, “A referendum was held for this public project, and the positive verdict of the popular vote was celebrated with a torchlight procession, an event that reflected a unique sensitivity and co-participation from the public. The mayor at the time, Mario Gallino, strongly supported us, adopting the project as his own. As a result, what we would now call a strong ‘awareness’ was also achieved.” [57]

Once this requirement was resolved, in September 1968, the proposal was finally approved, and the construction company was defined at this stage. It is important to highlight the significant roles played by engineers Guido Steiner and Enzo Vanetta throughout the process, albeit with distinct responsibilities. The former was responsible for the execution of the walkway, while the latter oversaw the construction, managed by the company Barizzi e Vanetta.

Another key moment came in November 1968, with the presentation of the project to a prominent municipal and cantonal delegation at the Bedano atelier. Faced with this formal and significant visit, which was crucial for affirming their capabilities to design such a complex and economically demanding facility, the architects decided to focus the delegation’s attention on a 1:50 scale model, assembled for the occasion in the atelier’s garden.

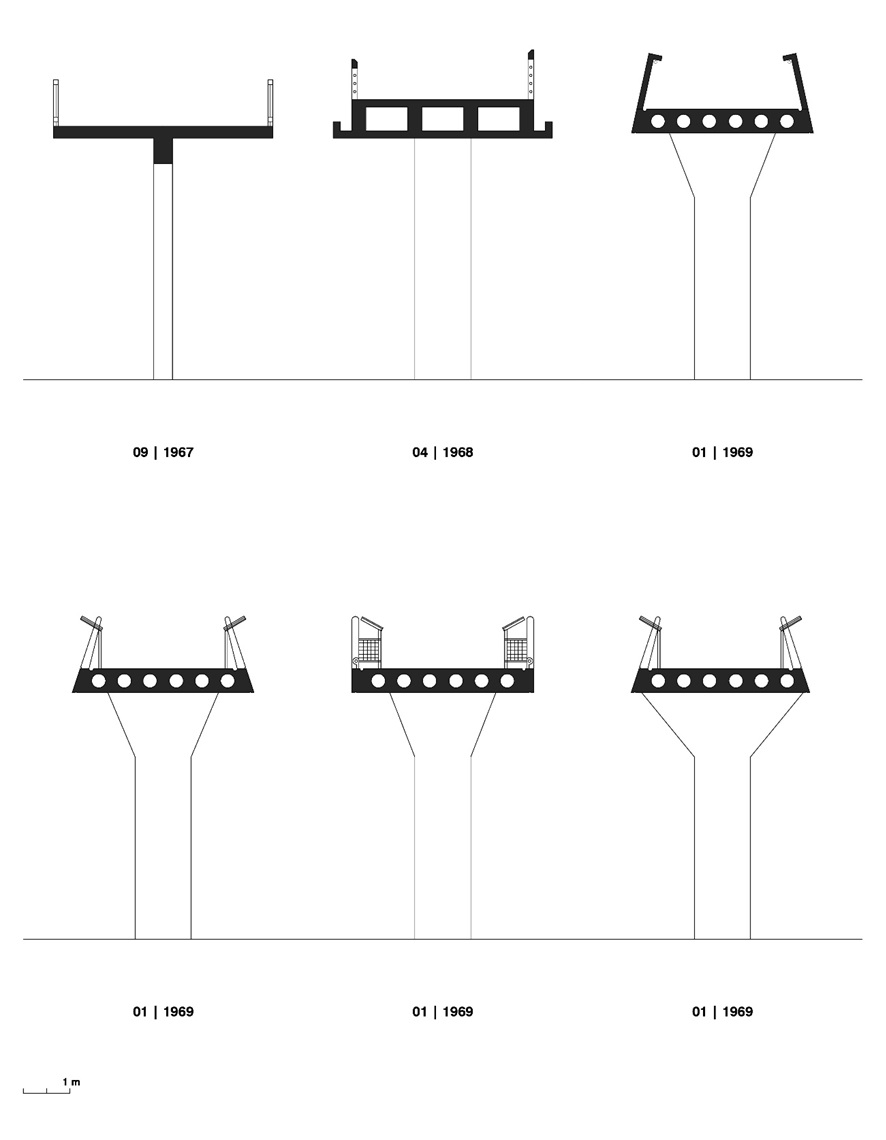

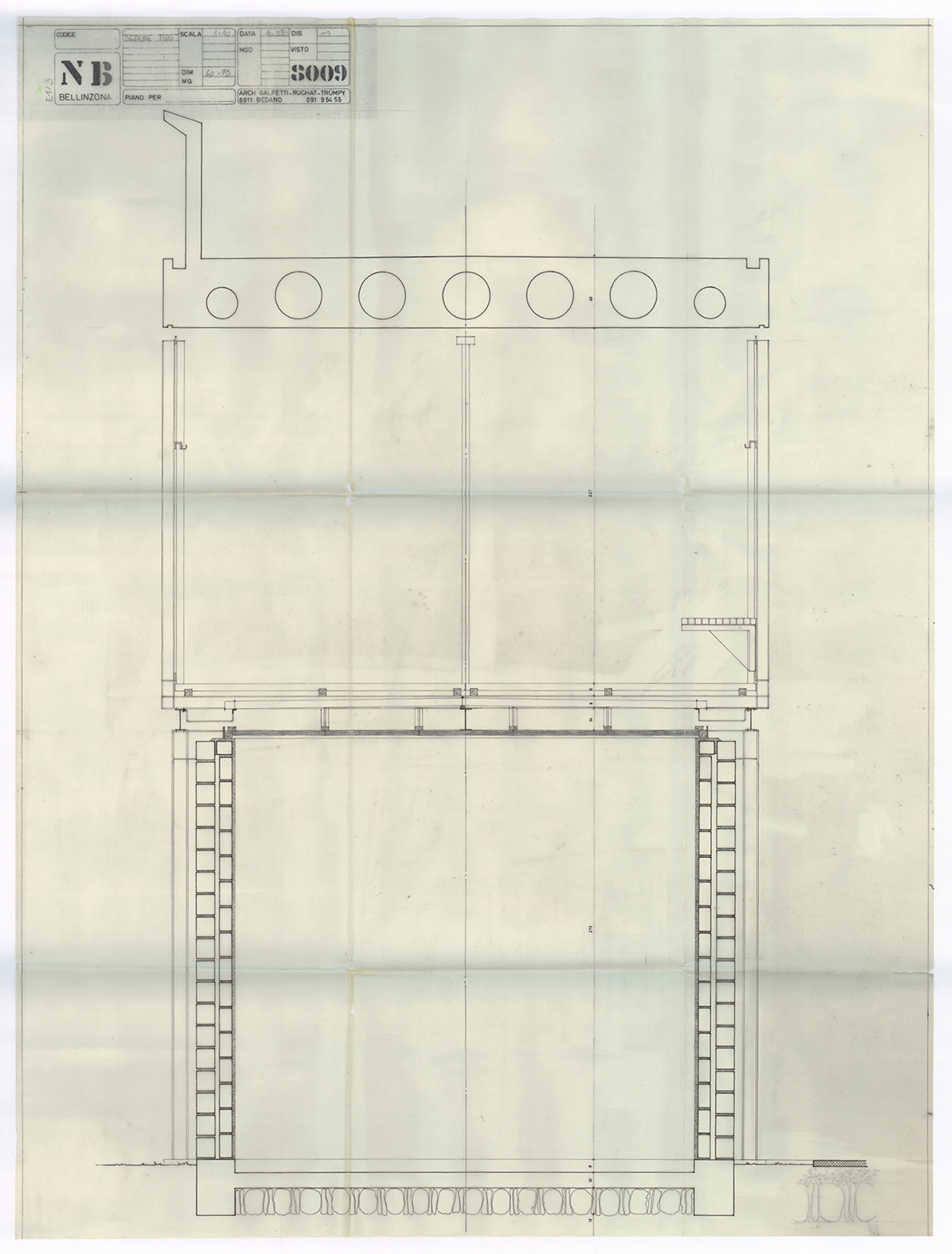

It is worth noting that the walkway measures approximately 375 metres in length, resulting in a model spanning 7.5 metres. At this stage, its structure was presented with an infrastructural footing, characteristic of major roadway axes. The programme spaces, designed beneath this walkway, were shown as structurally suspended from it.

The influence of major roadway infrastructures built in the Ticino region is particularly evident in the architects’ approach. These structures integrate into the landscape like contour lines that detach from the terrain’s orography, creating a new scale. Notable among them is Rino Tami’s work on the Chiasso–San Gottardo motorway, where the reinforced concrete of his architecture merges seamlessly with the mountains, becoming part of them.

This union between architecture and engineering is evident in the design of the Pools project. The various layers of expertise are harmoniously coordinated into a balanced composition, rather than a clash of forces—a characteristic shared with the works of other Ticino architects, such as Livio Vacchini and Luigi Snozzi, with whom Galfetti and Flora collaborated.

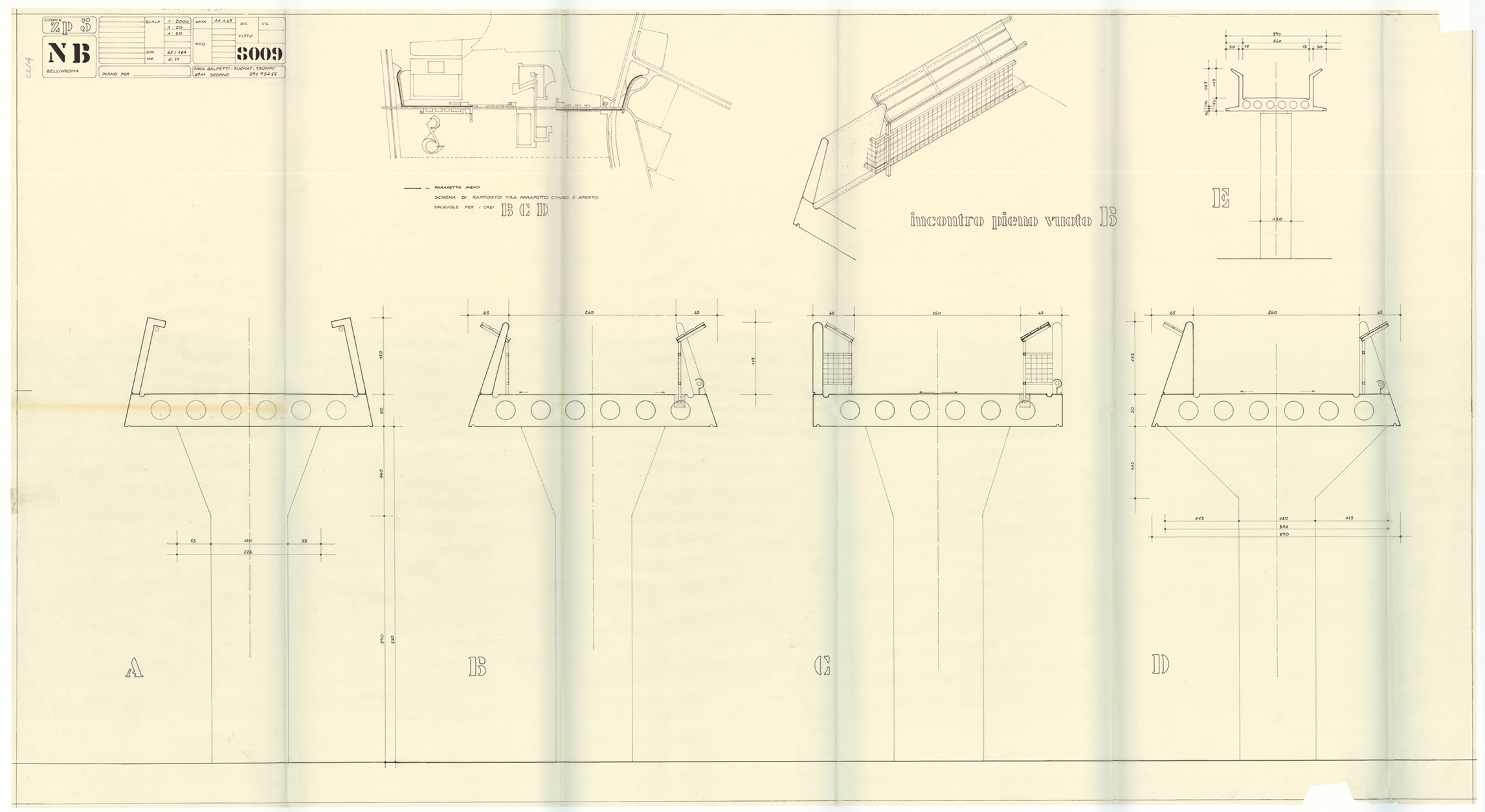

Figure 38 – Flora Ruchat-Roncati and the 1:50 scale model, placed in the Bedano studio (Source: Archivio del Moderno, 1968).

The profile of the walkway was obsessively redrawn by the architects, starting from the already mentioned infrastructural column, as though it were a motorway, until it was defined as a thin slab of 0.30m x 1.50m, with only two cruciform moments to address deformations. The modular solution for the walkway, measuring 14.64m in length for each segment, 3.90m in width, and 0.44m in thickness, began to take shape. This modelling, repetition, and corresponding structural autonomy started to transform the entire concept of the project, which initially suggested more diversity and structural interdependence among the elements.

What becomes apparent with the refinement of the initial concept is a clarified programmatic and formal solution, enabling the architects to achieve greater clarity in the design and its layout, becoming progressively less dispersed and more controlled, with increased precision in its detailing (08/1970). The theme of tectonics began to prevail in the design of the walkway, conceived as an infrastructure that joins and connects, drawing more from the relationships between architectural elements than as an isolated entity.

Contrasting with the regulatory rhythm of the pathway-time, as a measure within the landscape, are the drawings on the plain, made of organic patches, of desire, of emotion, in their relationship with water and vegetation, which, as it grows, begins to outline this incessant organic quality. Alongside this dual intervention, a third dimension is introduced: the landscape. The landscape as a blend of the urban genesis of the place, the strong presence of the Ticino topography, with its mountains and symbolic elements such as castles and walls outlining the slopes, in a new composition.

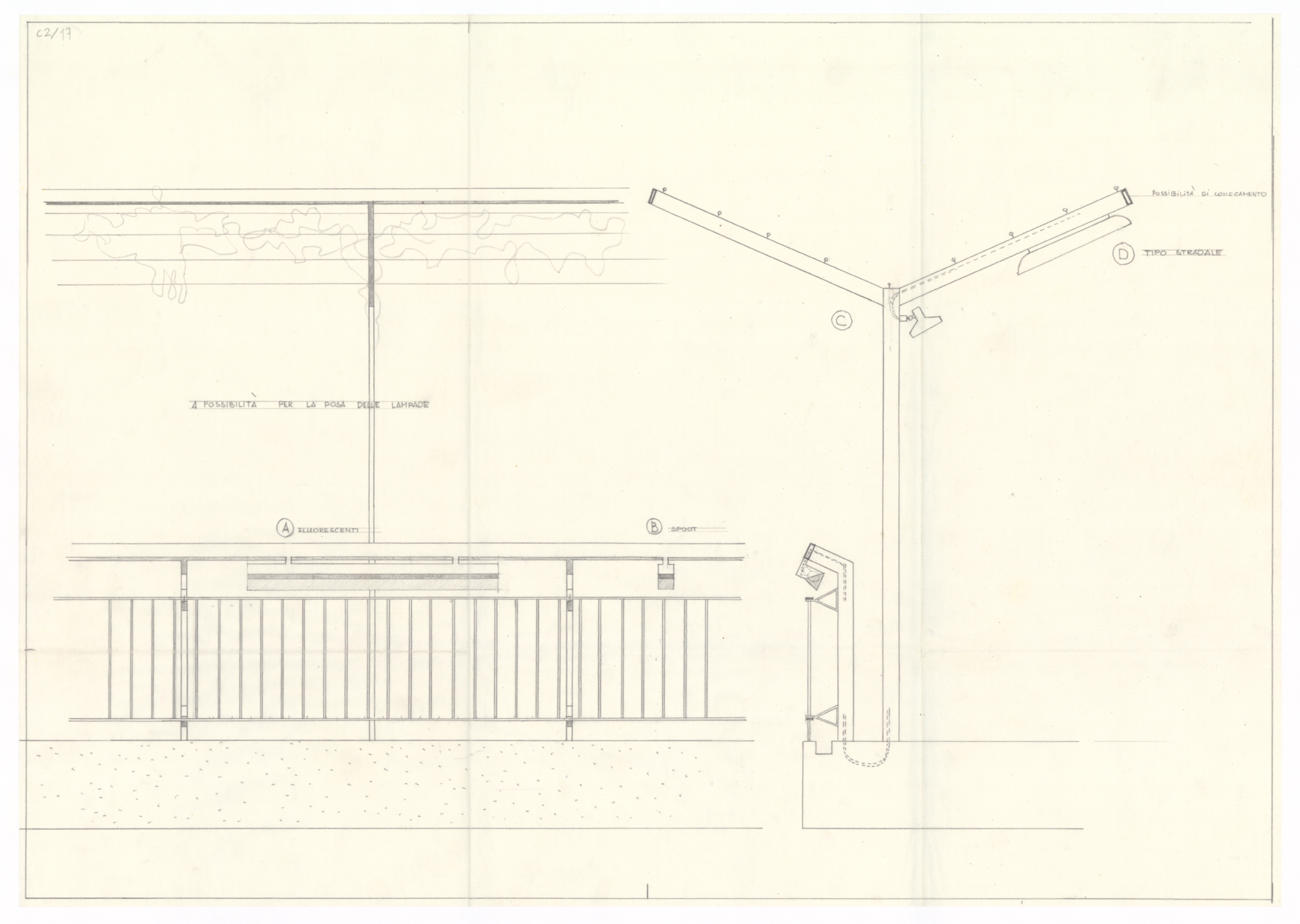

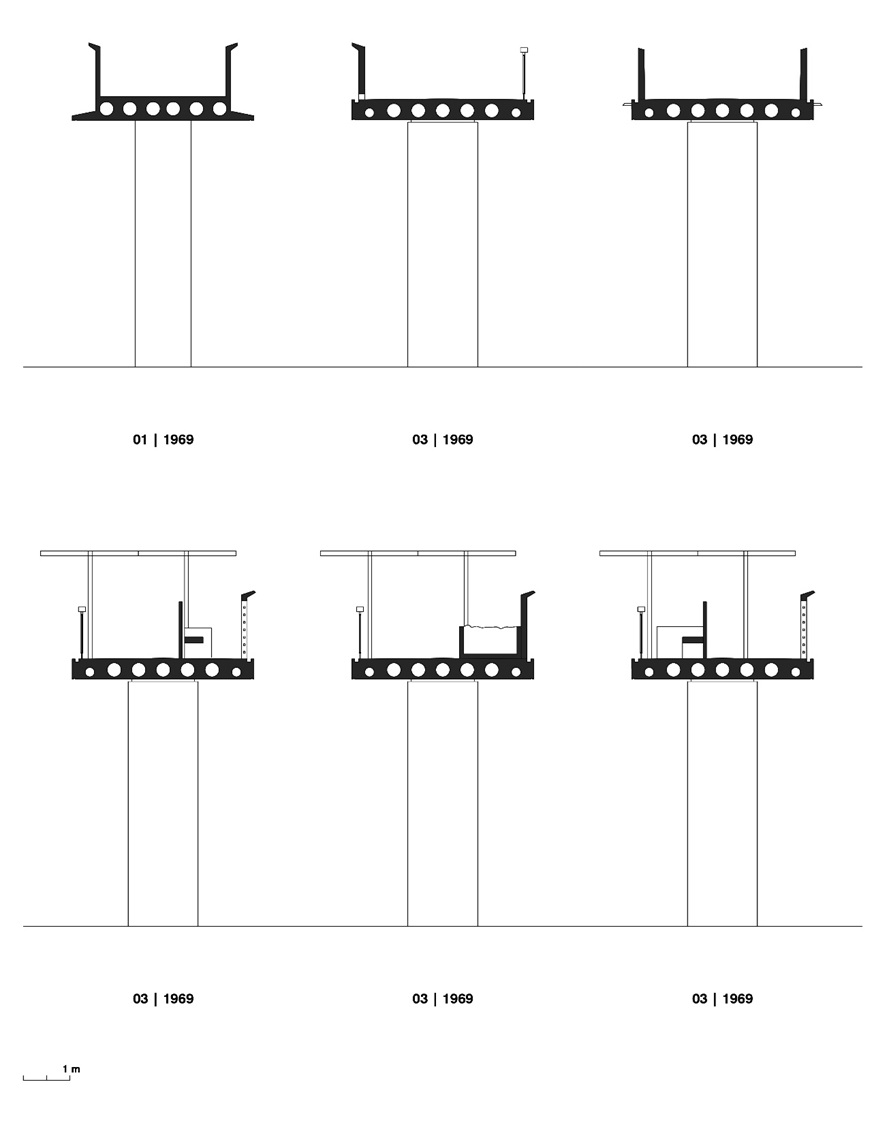

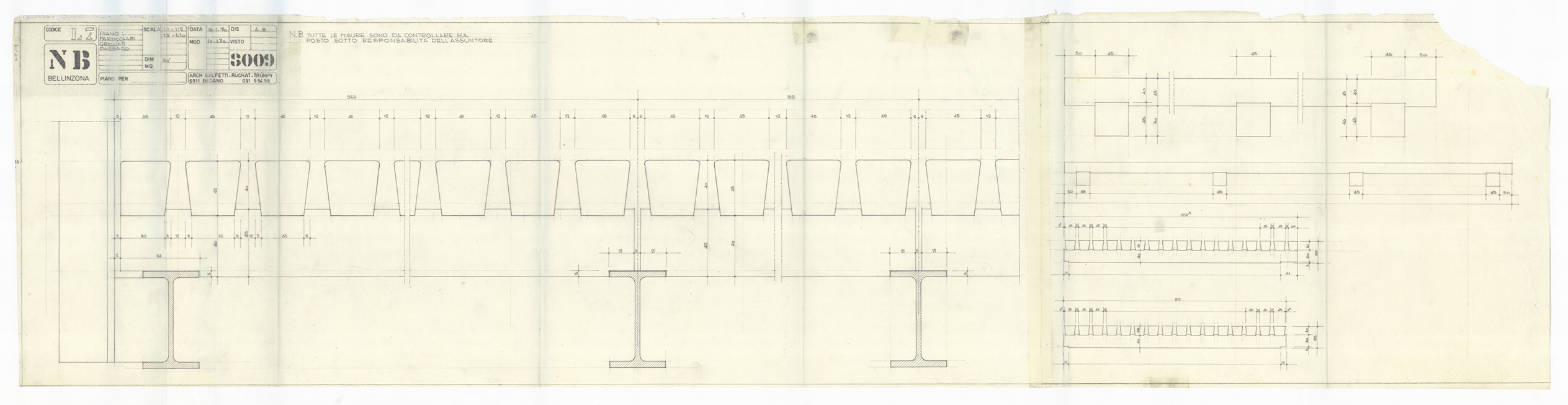

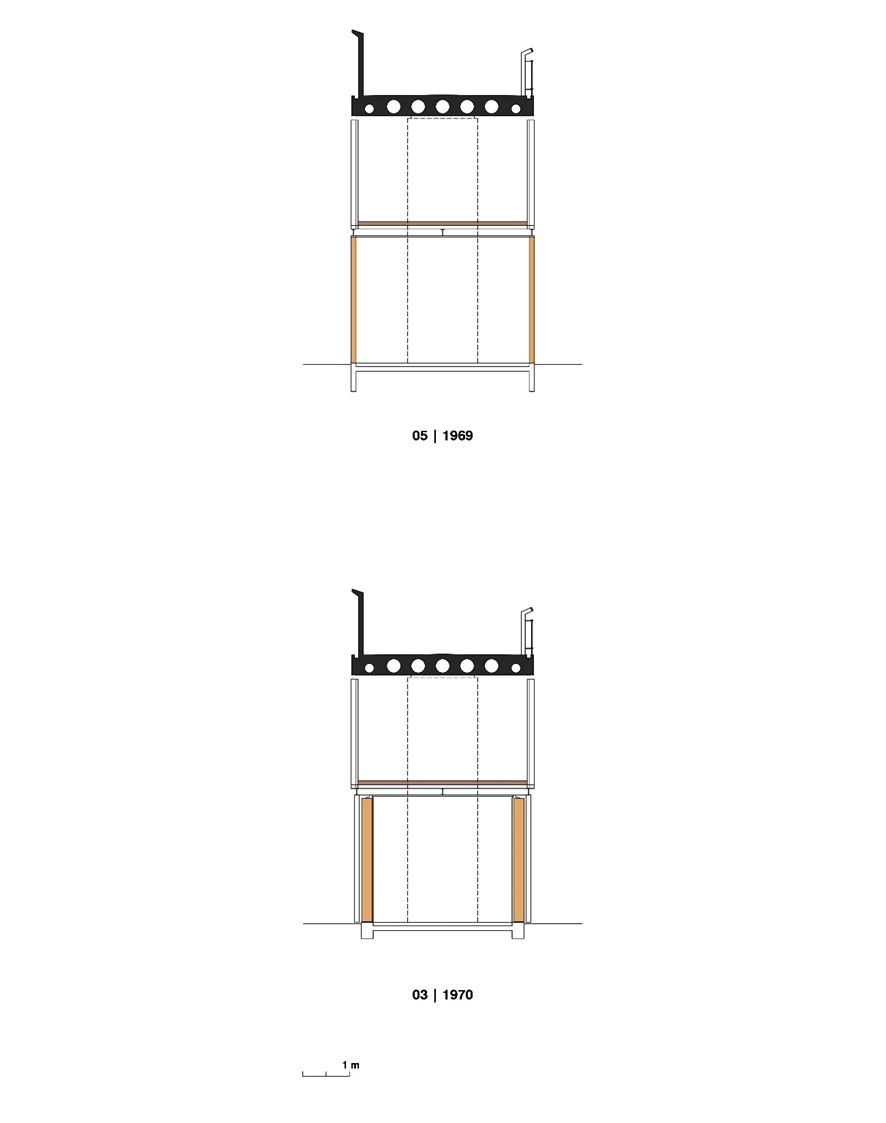

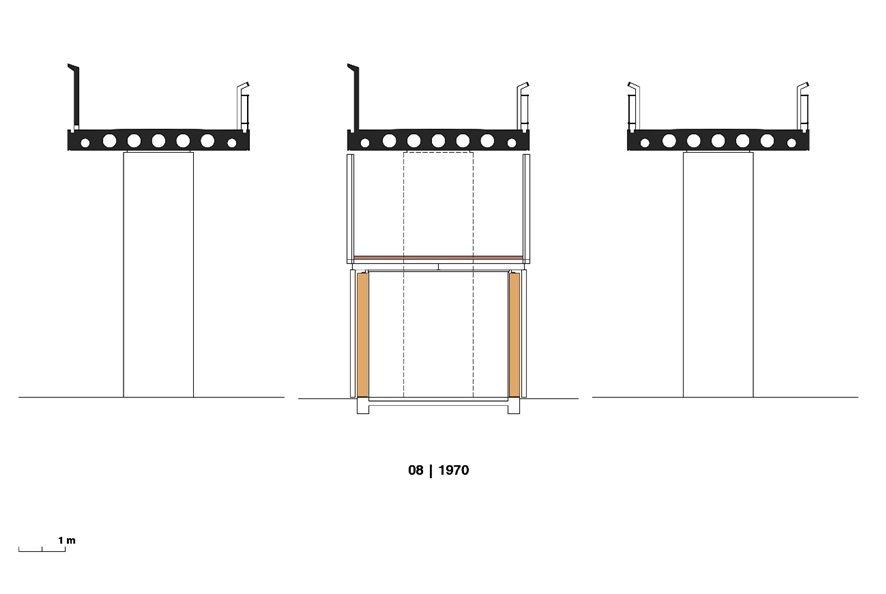

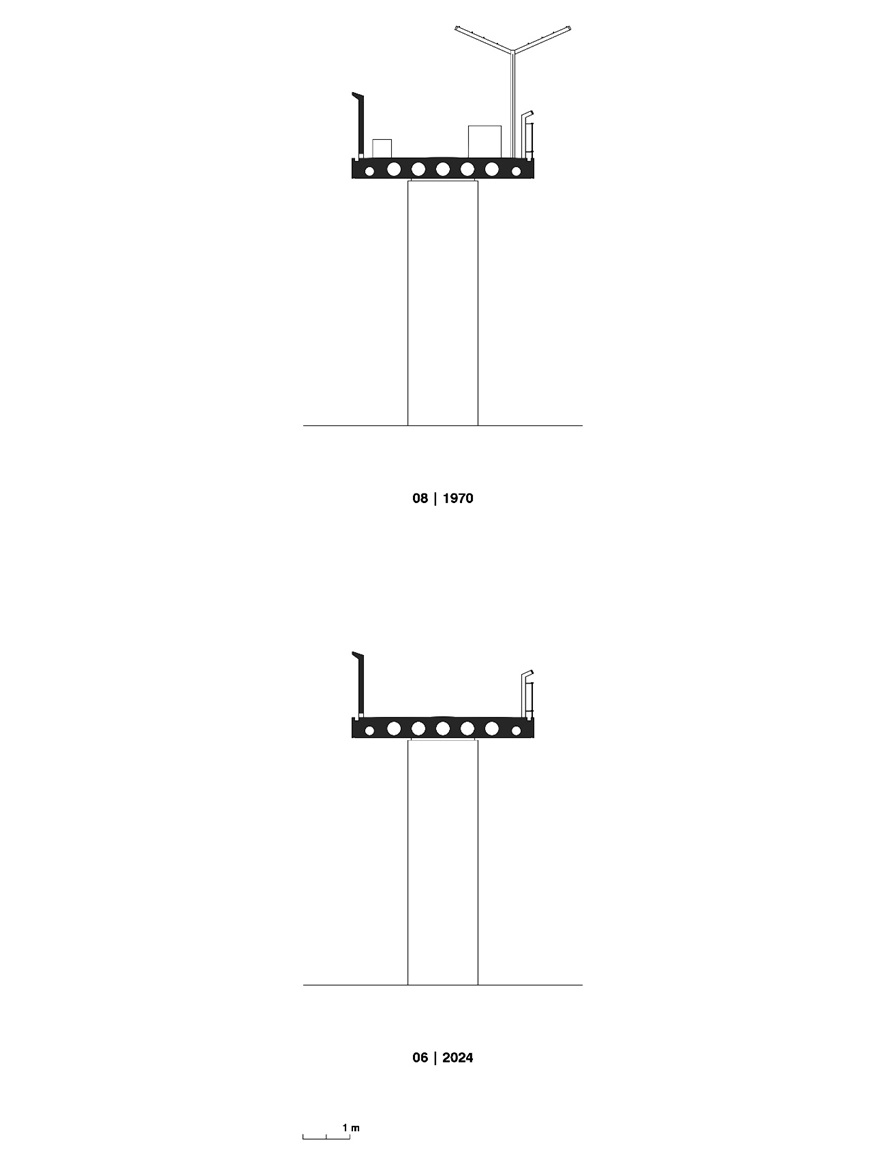

The various sections of the walkway, redesigned in this article, are analysed to clearly illustrate their development, from the competition phase (09|1967), through the various stages presented to the municipality in the years leading up to its construction (1968 and 1969), up to the moment of its inauguration (08|1970), and continuing through to the present day (05|2024).

Figure 39 – Schematic sections of the proposals developed for the walkway between September 1967 and January 1969 (Source: Drawn by the author from drawings in the Archivio del Moderno, 2024).

This graphic representation is considered important as it provides a clear and detailed way to deepen and compare this element, initially light and almost immaterial, which over time gradually incorporates weight as it is subjected to structural resolutions capable of addressing span, phasing, and the desired assembly process. The guard of the walkway profile, in the competition proposal, almost disappears, still lacking a refined language, and is composed of both horizontal and vertical metal profiles, reflecting an intentional lightness. The walkway’s thickness, still very slender, would require numerous columns in the intervention area (11|1967).

As structural and infrastructural concerns, such as rainwater drainage and electricity, begin to inform this key element, its profile undergoes several transformations in a detailed exploration of variants. The transition of its design, particularly in the temporal space leading up to its final production (04|1968 and 01|1969), is especially significant. Its flooring gains meaning with the definition of compacted concrete, featuring in-situ voids. The architects define numerous possible designs for the guards, in segments, visually enclosed with concrete, interspersed by moments of visual openings, with a galvanized steel structure. Lighting is now integrated. Comfort-related issues, such as rounded edges and inclined plane solutions for those observing swimming events, demonstrate the architects’ exhaustive desire to achieve a refined level of urban comfort.

The lighting, purposefully integrated with the galvanized steel guard, allows the walkway to be used at various times of the day, demonstrating its role as an urban axis, desirably of high mobility. Modular concrete benches appear along the walkway’s profiles, placed in the viewing area of the Olympic pool. Structures with thin galvanized steel profiles are designed for the implementation of a green roof, capable of providing shade to those observing the swimming events. The soil boxes begin to mark the rhythm of this structure, enabling the growth of the climbing plants.

The architects initiate the demarcation of the walkway’s guard design, alternating between galvanized steel handrails and concrete panels of two different heights, positioned to shield from the wind or simply to protect the view for those using the changing rooms on the intermediate floor.

This solution marks a tectonic significance supported by the prefabrication of the metal profiles and galvanized steel profiles for the guards. The fixings are exposed, providing clarity. The modular Thermolux panels, creating visually controlled environments in the changing rooms with diffused light, characterise these spaces with purity and spatial comfort. The modularity of these elements will allow for their replacement due to the intense wear from use.

All the equipment, such as benches, drinking fountains, and the entire signage, is designed by the architects, reflecting an obsessive control over every element of the project.

The detail of the solid walnut wooden flooring is sophisticated in its profile variations, depending on its location. It is bevelled to improve rainwater drainage or cut in a zigzag pattern to prevent the interior of the changing rooms from being visible at a lower level. The wood profile begins to be extensively used on the intermediate floor and in the stairway paving. The shadow cast by its detail is indicative of the deliberate metric proportion the architects aimed to achieve.

Figure 40 – Schematic sections of the proposals developed for the walkway, between January and March 1969 (Source: Drawn by the author based on drawings in the Archivio del Moderno, 2024).

Figure 41 – Section of the wooden panels, placed on the floor, January 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es T 36/4).

Figure 42 – Section of the wooden panels, placed on the floor of the changing rooms, January 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es T 36/3).

Figure 43 – Details of the placement of corrugated sheets beneath the wooden flooring and the welded gutter detail for water drainage, February 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es T).

Figure 44 – Details of the placement of the wooden flooring on the steps of the stairs, August 1969 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AdM, fondo Aurelio Galfetti, LG 21 Es T).

The theme of prefabrication is introduced to overcome production deadlines and facilitate replacement, given the expectation of intense use and the associated wear. The metric proportion between the sections of the various elements begins to be part of the structural justification, where the joints and all the fixing details, highly exposed, acquire a clarifying value in the aforementioned tectonic importance. The refinement and clarity of the final solution mark a constructive truth.

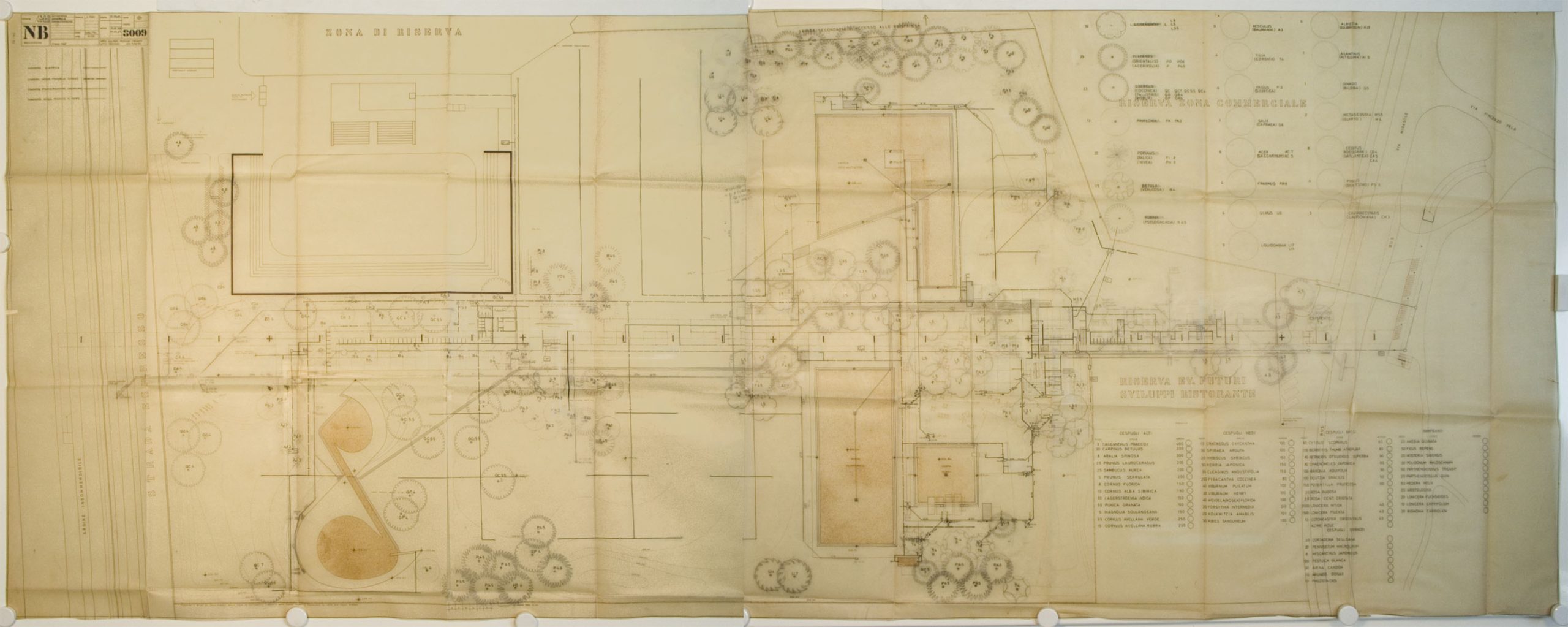

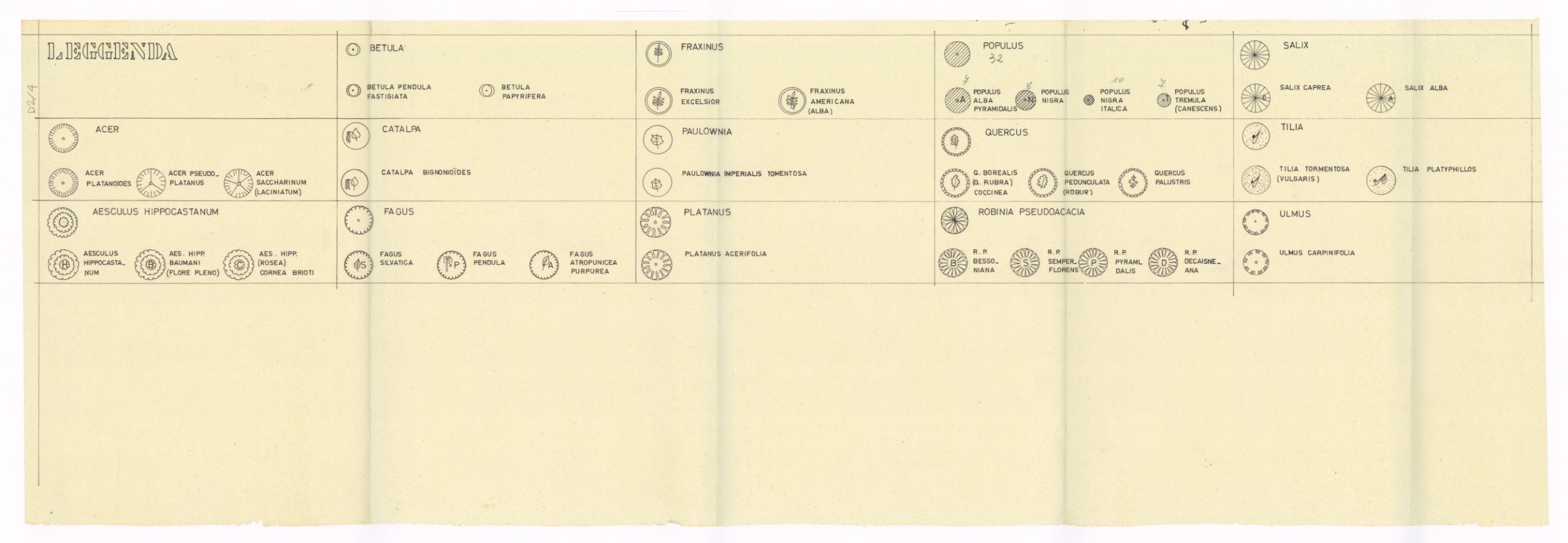

The planting plan evolved in reverse, starting from a geometric rationality and gradually approaching a forest-like organic quality. After initial, highly regulated experiences in its composition, the plan gradually liberated itself from an urban metric, taking on characteristics of a park. The abundant presence of water in the plain, combined with the local climate, has allowed the trees to reach centenary sizes within a span of 54 years. The architects exhaustively studied the most suitable species and designed the planting plan to define concentrations, irregular lines, and small groves of native species characteristic of a riparian gallery, such as: plane trees, beeches, ash trees, elms, willows, birches, poplars, oaks, elderberries, and more. According to Nicola Navone, the architects attached leaves from the trees to the walls of the Bedano studio to better interpret their composition in the landscape.

Figure 45 – Planting lan, 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AUTCB).

Figure 46 – Planting Plan Key, 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, AUTCB).

Returning to the beginning of the route, the inflection of the access to the walkway from the city towards the Ticino River is highlighted. This access, executed by a gentle ramp of slender concrete walls with thicknesses that are currently difficult to achieve (10 cm), overlooks the Gymnasium Cantonal by Alberto Camenzind and Bruno Brocchi, previously mentioned. We argue that by considering the architecture and the value of its symbols, the pathway intentionally establishes an inflection, so that this educational facility is viewed in contrast to the three castles and the mountain, in a succession of planes whose depth of field demonstrates an intentional territorial reading.

Figure 47 – Photograph of the existing model in the Archivio del Moderno (Source: Photograph by the author, 2024).

After reading the overall composition and the development of the walkway section, another essential reading can be added, consisting of the representation of the cut, where it integrates the programme at the intermediate and plain levels. When the various floors incorporate programmatic functions, the fusion between infrastructure and architecture occurs. The section proves to be foundational.

To the initial strategy of making the various components vertically coplanar, a new solution is refined, calling for the visualization of the various elements and their joints in an evidently highlighted manner. Light passes through the various levels, revealing the joints, and their constructive independence takes on an inaugural intent.

The concrete platform, with its slender blades, is juxtaposed autonomously with the steel structure, supported on the ground, welded and bolted, manifesting the module and its repetition, highlighting all its joints. The solid brick walls, in the ochre colour characteristic of the region, resting on the plain, are implanted independently and not coplanar, allowing the shadow and emphasis of each element to form a new constructive lexicon. This manifests the design’s meaning, with the real gravitational freedom highlighting the joints in the architectural composition, unravelling its constructive process.

Figure 48 – Cross section of the walkway, March 1970 (Source: Archivio del Moderno).

Figure 49 – Schematic sections of the proposals developed for the walkway, incorporating programme on the intermediate floor, between May 1969 and March 1969 (Source: Drawings by the author, based on drawings from the Archivio del Moderno, 2024).

Figure 50 – Schematic sections of the proposal developed for the walkway, with and without incorporation of programme on the intermediate floor, August 1970 (Source: Drawings by the author, based on drawings from the Archivio del Moderno, 2024).

4.3 Built Work | Built Work Today

Having overcome the mentioned popular referendum, construction works began in the same year, 1968, allowing the public opening in August 1969. Although still incomplete, this opening provided the desired and necessary access to the pools, without preventing swimming competitions. The official inauguration would only take place on 1 August 1970, even though the final connection at the edge of the embankment on the Ticino River side remained unfinished, with its construction only beginning at the end of 1971.

The modular construction process enabled swift production and on-site installation. The autonomy of execution, with the bolting together of the various iron elements, also proved efficient for preparation in the workshop. The wooden flooring, made of panels comprising several wooden planks, was also adapted to ensure the required speed of assembly and potential disassembly during the winter months. The prefabrication, modularity, and bolting of the assembly stood in contrast to the construction of the concrete walkway planes, whose metal truss, designed to structure the piece’s formwork, resembled a project of road-scale dimension and complexity.

The moment of inauguration highlighted the importance of this project for the entire Ticino region and its surroundings. This facility would leave an urban mark on Bellinzona and influence an important generation of architects, who remember their first visit as an enlightening event, a moment of wonder that revealed the significance architecture has and will continue to have in this place.

In its initial phase, shortly after its inauguration, the walkway near the Olympic pool was punctuated by concrete benches integrated with the previously mentioned metal structure, where climbing plants timidly began to appear alongside their respective soil boxes. The vegetation on the plain, still sparse, lacked the maturity needed to produce shade.

These elements punctuating the walkway were gradually removed or repositioned, allowing for an increasingly clear reading of the concrete pathway. The galvanised steel profile structure, designed to support the growth of climbing plants, was deemed superfluous and subsequently eliminated. The design became progressively more refined and illuminating.

Figure 51 – Schematic sections of the built proposal for the walkway, at the time of the inauguration, August 1970, and today, June 2024 (Source: Drawings by the author, based on drawings from the Archivio del Moderno, 2024).

The native vegetation surrounding the entire pathway has now reached an exuberant maturity, allowing for the removal of the already mentioned shading elements. Its prominence in the project’s significance, as presented in the sectional drawings of the competition proposal, has now reached the intended scale, underscoring the importance of the landscape as a cultural factor of integration and connection with the site, as well as a temporal element in its meaning.

The walkway is revealed in winter, when the deciduous leaves expose this infrastructural gesture within the landscape, and it hides in summer, when the shade protects it, with the vegetation taking on the role of extending the pathway longitudinally, shaping a sense of topographical continuity.

In the decades that followed, some materials, worn down over time, were replaced, such as the solid wooden planks substituted with composite wood decking. The alteration of their section changed the proportions and metric balances previously achieved. Its shadow on the plain shifted, as did its colouring.

After the classification of the work as a site of cantonal interest in 2010, economic resources became available for its urgent preservation. The restoration project began in 2019, and to this day has delivered significant cleaning and restoration of the concrete elements on the walkway, stairs, and ramps. The treatment and replacement of the galvanised steel railings are also evident.

Further decisions are expected to be made in the future, such as replacing damaged or altered flooring to restore the original materiality and metric design of the surfaces. It is also hoped that the concrete finishes, so highly sought after by the architects for the various pools, will be reinstated, reviving the initial references of the design team. By paying homage to Le Corbusier, they also keep alive the collective memory of the authors’ childhoods, where the smooth, polished river stone naturally coexists in symbiosis with the carved stone of the Roman bridges. The craftsmanship demonstrates itself as alive, in dialogue with the landscape, re-establishing the essence of the place.

Figure 52 – The construction of the walkway, 1969. Note the detail of the joint for each section, executed on-site, as well as the iron lattice used for its formwork (Source: Archivio del Moderno, ALG, AUTCB).

Figure 53 – The construction of the metal structure, 1969 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, ALG, AUTCB).

Figure 54 – View of children’s pool and walkway, 1971 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, ALG).

Figure 55 – View of the walkway, from the access stairs to the embankment, 1971 (Source: Archivio del Moderno, ALG).

5. Echoes and influences

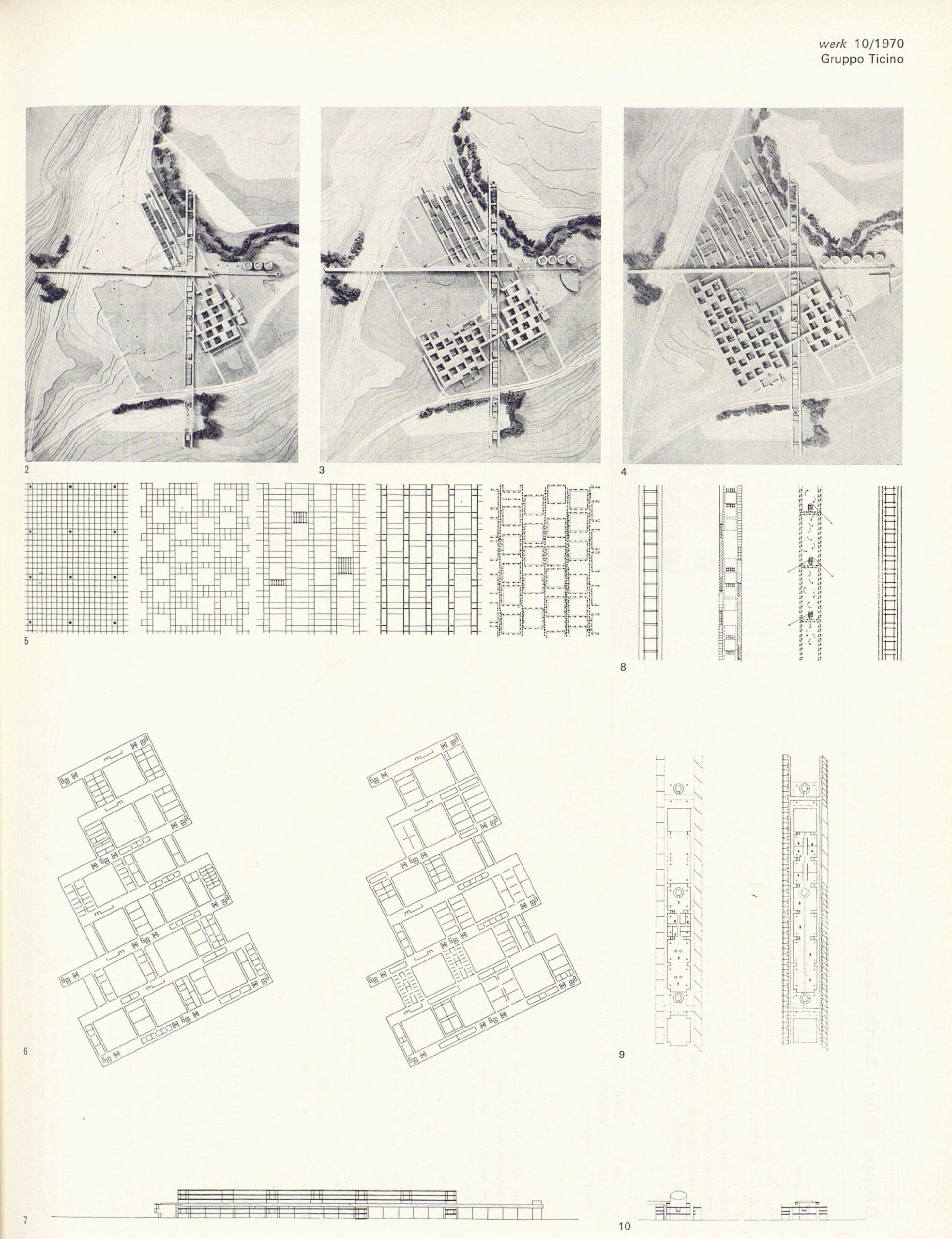

Shortly after the construction of the Pools, Aurelio Galfetti and Flora Ruchat-Roncati joined Mario Botta, Tita Carloni, and Luigi Snozzi (the so-called Ticino group) in preparing a proposal for the master plan competition for the new Polytechnic of Lausanne. The proposal, submitted in 1970 but not selected, reveals clear influences between the infrastructural gesture of the Pools, in their territorial integration in Bellinzona, and the proposal for the Master Plan of the New Polytechnic of Lausanne. In the latter, the strong North-South and East-West axes stratify uses, elevate functions, and call for evolutionary solutions at the ground level.

The North-South axis of the proposal is particularly enlightening in its use of an elevated pedestrian connection as the project’s structuring element. It consists of two lateral slabs that incorporate housing for faculty and students. Between these slabs, various shared functions take place, such as exhibition halls, a library, restaurants, shops, and other interconnected facilities, all linked by the previously mentioned suspended pedestrian pathways.

The formal and programmatic experience of the Pools clearly echoes in the search for new solutions, capable of surpassing territorial interpretations through an infrastructural gesture, creating new models of urban landscapes.

Figure 56 – Competition Proposal, published in the journal Werk, No. 10, Issue 57, October 1970 (Source: E-Periodica – Das Werk: Architektur und Kunst = L’oeuvre: architecture et art – Umfrage zur Architektenausbildung).

A few years later, Álvaro Siza Vieira, confronted with the influence of the built fabric of the city of Évora and its Roman infrastructural reminiscences shaping the scale of the territory, became unsettled upon identifying watercourses crossing the area designated for the future Malagueira neighbourhood. He translated this unease into the insertion of a complex element, compulsively redesigned, sometimes described as a conduit, other times as an aqueduct, within the overall plan for the Malagueira neighbourhood.

This elevated element, which conveys electricity, water, gas, and telecommunications, is repeatedly drawn in Siza’s sketches as something transposable and passable. Ultimately completed only as an infrastructural conduit, it is constructed with cement blocks in search of an economy of means combined with modular repetition, allowing for rotations and altimetric variations, in an intentional territorial reading that shapes a fundamental element of the landscape.

As Rodrigo Lino Gaspar provocatively notes in his article [58],

“The aqueduct embodies what Álvaro Siza describes as another scale or the introduction of a new complexity. The result is a self-referential element, an artificial pre-existence – a contradictory body that raises more questions than it answers. Should we consider Malagueira an example of how to build resilient cities?”

We can draw parallel readings between the Bellinzona Pools and the Malagueira Aqueduct in their infrastructural gesture, which, by surpassing the scale of the intervention area, relates them to the design of the territory. The landscape informs the architecture so that it can design the infrastructure that communicates with the place.

Figure 57 – Sketches by Álvaro Siza Vieira, on the Aqueduct (Source: Drawing Matter Collection, 2512.1 | 2393.05)