Maria Matos Silva

mmatossilva@isa.ulisboa.pt

Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa; CIAUD, Centro de Investigação de Arquitetura Urbanismo e Design, Faculdade de Arquitetura, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal

Ana Beja da Costa

anabejacosta@fa.ulisboa.pt

CIAUD, Centro de Investigação de Arquitetura Urbanismo e Design, Faculdade de Arquitetura, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal

To cite this article:

MATOS SILVA, Maria; BEJA DA COSTA, Ana – Culture in ecology – a revolutionary tradition. Estudo Prévio 25. Lisbon: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, dezembro 2024, p. 237-253. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/25.8

Received on July 26, 2024, and accepted for publication on October 9, 2024.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Culture in ecology – a revolutionary tradition

Abstract

Ecology is nowadays culturally valued, which is not the same as saying that there is culture in ecology. It is true that technical evolution has enabled incredible and extremely ingenious advances that should be valued and used. Even so, we need to move towards new paradigms and enrich current knowledge and practice by calling for projects that promote the establishment of ecological, cultural and aesthetic values through convincing relationships, whether experimental or not, between all elements, whether living or material.

Public space offers this possibility if thought of from an ecological category, reinforcing the role of design practice in re-establishing old relationships or promoting new ones. A system of broadly-based public spaces that, by integrating ecology-based thinking, embraces the landscape in such a way that the persistent anxiety of its control is pacified by a preference for projects that are open to uncertainty.

Keywords: Landscape Architecture, Ecology, Culture, Public Space

1. “Landscape as an Expression of Culture” (Cabral, 1967)

Over time, our relationship with the natural systems we are part of has changed. Individual and community experiences and memories have created collective memories, shaping different cultures, different ways of being and acting in the world in which we live. This means we design different landscapes which reveal this culture. In 1967 Francisco Caldeira Cabral wrote about “Landscape as an Expression of Culture”, an idea also immortalised by Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles when stating that “… the landscape is the ultimate exponent of a people’s culture…” (TELLES, 1985), in its best and worst aspects.

If we look, for example, at the water system, one of the basic systems of the landscape, we can discern a clear differentiation between territories because of the different ways this system has been managed and shaped over time in line with different ecological, social and economic priorities. As Viganò et al (2016) remind us, although the processes associated with water are intrinsically dynamic and inconstant ones, the water system leaves the most lasting imprint on the landscape. In the same way as the water system structures the landscape, the mutability of its processes is also a structuring system. In fact, a river landscape is not only water and its associated water systems, it also reflects the relationship between this entire system and the related community.

As we are aware, the landscapes “before” and “after” the industrial revolution are quite different. At that turning point in history, traditional practices that inevitably presupposed an equal power relationship between communities and natural processes, shifted progressively towards activities whose main objective was to get the most out of the natural systems and their resources by seeking to control them. Of course, the serious natural disasters that later occurred made it clear how utopian is this ambition to completely control any natural system. Nowadays, it seems to be common knowledge that, not only is this a useless concept, but it is also impossible.

As proposed by Brown et al (2008) [1], in renowned public space projects in Lisbon we can identify different evolutionary “stages” of a cultural relationship with the natural systems. Some projects were ahead of their time – such as the Parque do Campo Grande planned by Ressano Garcia in 1903 (never built) (SILVA, 1989), or the National Stadium project at Jamor by Caldeira Cabral (Andresen, 2001: 60-97), or the abandoned 1950s plans by Caldeira Cabral and Ribeiro Telles for the regeneration of the Avenida da Liberdade (DINIZ, 2023). Others are examples of contemporary or even avant-garde thinking, such as the Parque do Tejo e do Trancão (Hargreaves Associates, João Nunes – PROAP, 1994-2004) or the Parque Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles (NPK, 2021). Others can even be considered as being behind their time, such as the commission for a General Drainage Plan for the city of Lisbon (MATOS SILVA, 2016) [2].

2. Ecology-based thinking in Landscape Architecture design

In 2022, the Landscape Architecture course in Portugal celebrated its 80 years of existence. It is one of the oldest European institutions teaching Landscape Architecture. While the fact confers a degree of maturity, what is more interesting is what these 80 years of history contributed, namely in terms of accumulated knowledge and experience.

Taking the motto proposed for this dossier No. 25 of the journal Estudo Prévio, of thinking about the city and the public space after the 1974 Revolution, as well as about national landscape architecture projects, can we say there is a significant difference in the way of designing between the “before” and the “after” of the Revolution?

The idea of Landscape Architecture inherited from Caldeira Cabral as “Ars Cooperativa Naturae”, or “the art of convincing nature to collaborate with us ”(ANDRESEN, 2001: 106, trad. autoras), defines the discipline as a propositional practice. It implies action for change, and, because it is an art, it has an intuitive and emotional, aesthetic, affective and a cultural side, as well as a technical side. In the latter, this is associated with having a good scientific knowledge of the relationship between humans and the processes of (what is also their) nature. As an art based on nature, Landscape Architecture has thus embedded, in an interconnected way, culturally based thinking which questions what needs to be changed, aesthetically based thinking focused on what awakens emotions and creates memories, and ecology-based thinking, which is, fundamentally, scientific and technical.

As part of the celebrations marking the 80 years of the Landscape Architecture course in Portugal, the book “Portuguese Landscape Architecture Education, Heritage and Research: 80 Years of History” (MATOS SILVA et al, 2024) was published. This contains a series of articles looking at the history of its teaching, the enduring influence of key figures, and major milestones that shaped the field and the relevance of the discipline [3]. In general, as we go through the chapters of this book, we are transported back to the foundations of ecological thinking, something that is fundamental for teaching Landscape Architecture as well as a powerful tool for professional practice [4]. The editors organise this thinking into the following three points: 1) multiplicity, diversity and interconnectivity of relationships; 2) systemic processes and cycles with dynamics that are always open-ended and 3) uncertainties and variabilities as driving forces of positive change (MATOS SILVA, 2024):

- Like human beings, landscapes are much healthier and more resilient the stronger, safer, diverse, more complex and multiple their anatomies and their relationships and interconnections are, both internal and external to their systems. A principle of ecological thinking that continually challenges existing trends that favour any kind of monoculture (culture here understood in all its senses, from growing plants or breeding animals to education and civilizational values).

- On the other hand, understanding and respecting natural cycles, such as the water cycle, the nutrient cycle or energy flow, as well as the recognition of their open-ended dynamics, are strongly connected to a particularly intimate relationship with the “time” factor. Time, as the underlying force of any process, it is therefore understood as a value in itself. As J. B. Jackson says, “The act of designing the landscape is a process of manipulating time (Jackson, 1984).” Following the same line of reasoning, João Nunes develops the idea of “domestication” when describing his way of working and designing using natural processes for the benefit of Humans (NUNES et al, 2011). This acknowledges the existence of and the need to respect existing multiple “times” as constituents and actors in landscape design, and also the uniqueness of moments. In this sense, long-term thinking as a “modus operandi”, together with permanent elasticity between scales and the times of different processes, is also a characteristic that is inseparable from ecological thinking. As is the certainty that any intervention will always be an unfinished work.

- Finally, the proposition inherited from the father of Landscape Architecture in Portugal – of developing a natural continuum [5], or a landscape in a continuous dynamic equilibrium, namely by always seeking for a solution that balances exchanges within/outside the cycles and its constituent open-ended systems. This process is seen as the catalyst for the greatest creative achievements of ecology-based thinking. The restlessness of continually seeking to improve the equation of natural resource management and global energy flows to obtain a result that should, ideally, aim at zero, is very much in evidence in many Landscape Architecture projects, which used cultural and natural systems in an artistic way to solve complex problems such as flooding, water scarcity, mobility, biodiversity loss or resource management.

Returning to the question that prompted this essay, if on the one hand, over eight decades one could expect a cultural transformation, as a result of specific social and economic circumstances, has there been a cultural revolution in the ecology-based principles behind the practice of Landscape Architecture? If we understand formal or naturalistic layouts as expressions of particular cultural currents, on the contrary, and by hypothesis, the traditional ecology-based technical-scientific principles are the same, possibly reinforced with greater accumulated knowledge and experience.

3. Before and after the 25 April 1974 Revolution in the 80 years of Landscape Architecture in Portugal

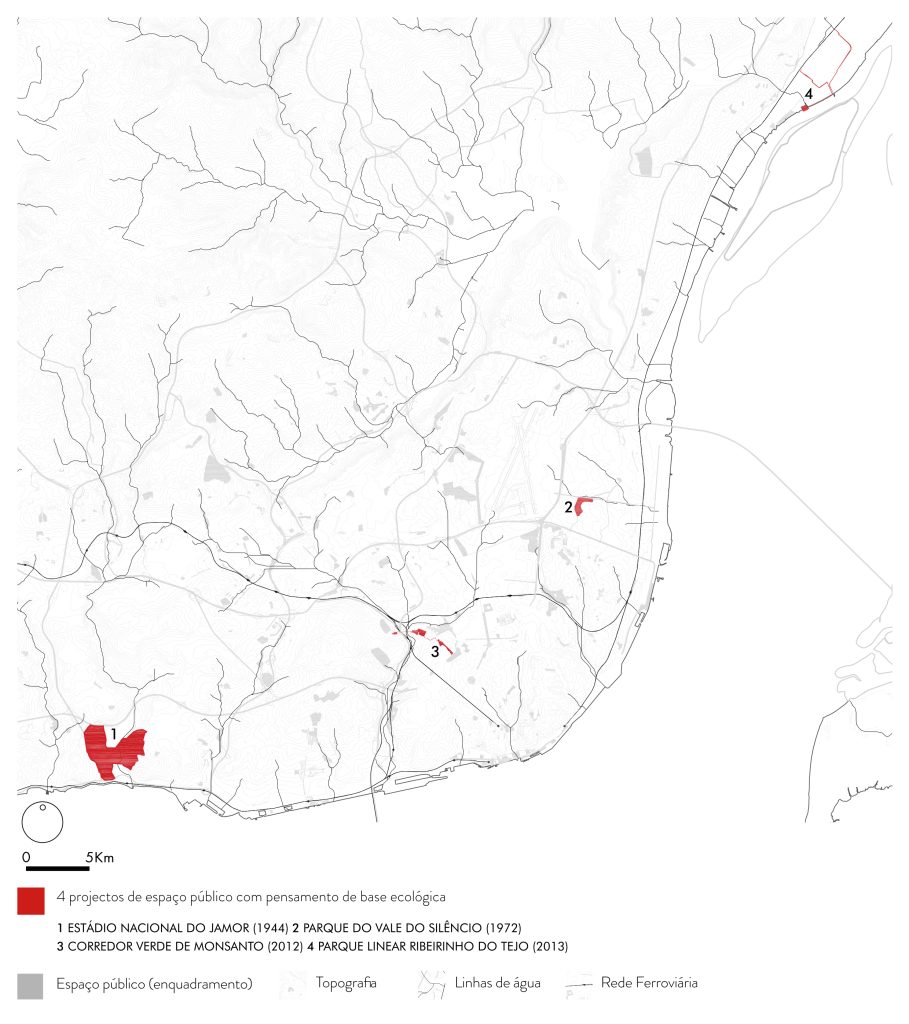

We discuss four public spaces designed by landscape architects in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (AML) (Figure 1), two before 1974 – Estádio Nacional (1938) and Parque do Vale do Silêncio (1967) – and two after – Corredor Verde de Monsanto (2002 – 2020) and Parque Linear Ribeirinho do Tejo (2012), in order to try to find whether they reflect the above principles of ecological thinking.

Figure 1 – Location of case studies

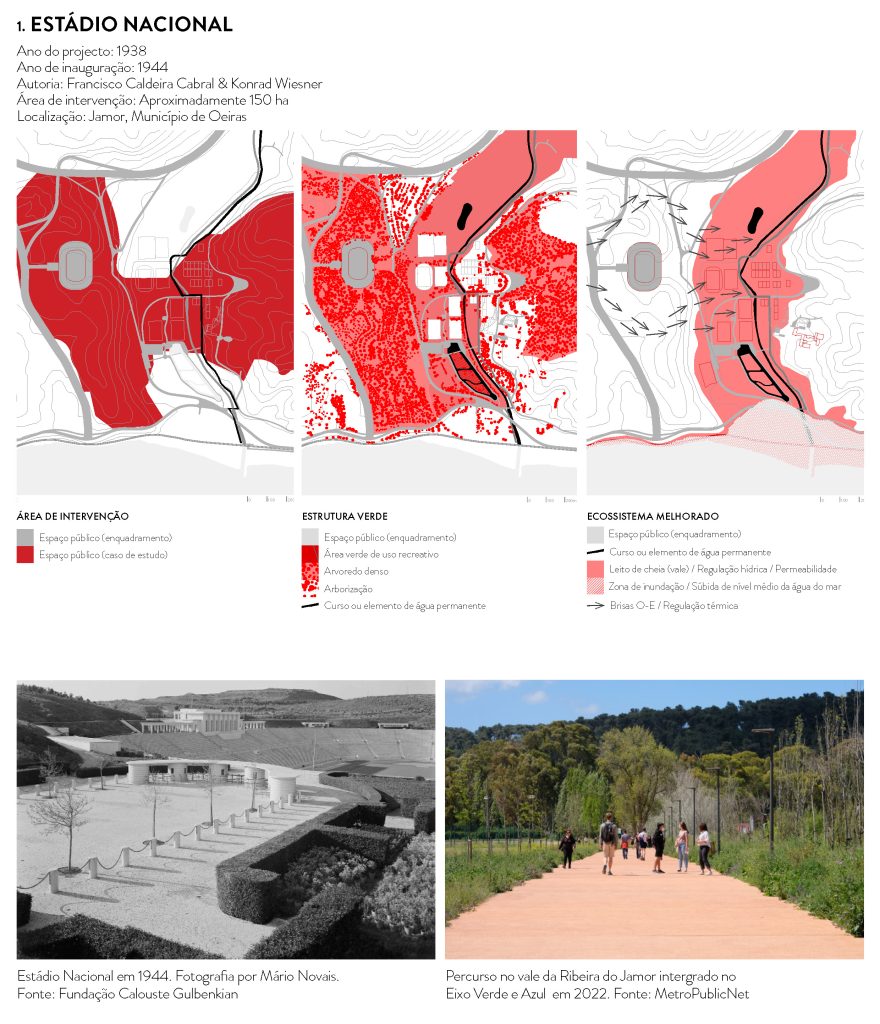

3.1 Estádio Nacional [National Stadium]

The premise behind the construction of the National Stadium in the Ribeira do Jamor valley was widely studied and discussed. In particular, in the initial report by Francisco Caldeira Cabral on the draft proposals presented by Cristino da Silva, or by Jorge Segurado. Both proposed building the stadium and the entire secondary built and road infrastructure along the line of the valley. Three principles based on the physiography of the place were incorporated into the project based on this report: the topography, the dominant winds and the soils. This led to the proposal to build the main stadium on the hillside, framed by a curtain of dense vegetation to offer protection from the prevailing north-south winds. In addition to scenically framing the stadium and enhancing perspectives and viewpoints, it provides bioclimatic comfort, shading, as well as close contact with nature for those using the stadium (Figure 2). The Jamor river valley was kept free of construction, preserving its rich soils, water dynamics and proximity to the coastline, which is only interrupted by the existing railway line (ANDRESEN, 2003).

The enhanced ecosystem

The National Stadium project coincided with the beginning of the practice of landscape architecture in Portugal [6]. The ecological foundations of the project were strategic, and still today demonstrate the currentness and sustainability of its design principles. It preserved the complexity of the original ecosystem, and improved this by constructing a richer flood plain. Due to the possibility of optimising its use, as well as extending the sports and leisure functions and infrastructures, the project maintained the required flexibility for the functioning of the water infrastructure. A recent addition is the Eixo Verde e Azul (Green and Blue Axis project, 2018-21), which extends along an ecological corridor and a linear network of pathways along the Jamor River – part of an inter-municipal collaboration between Sintra, Amadora and Oeiras (SANTOS; COSTA, 2023: 49).

Figure 2 – Interpretative summary of the case of the National Stadium

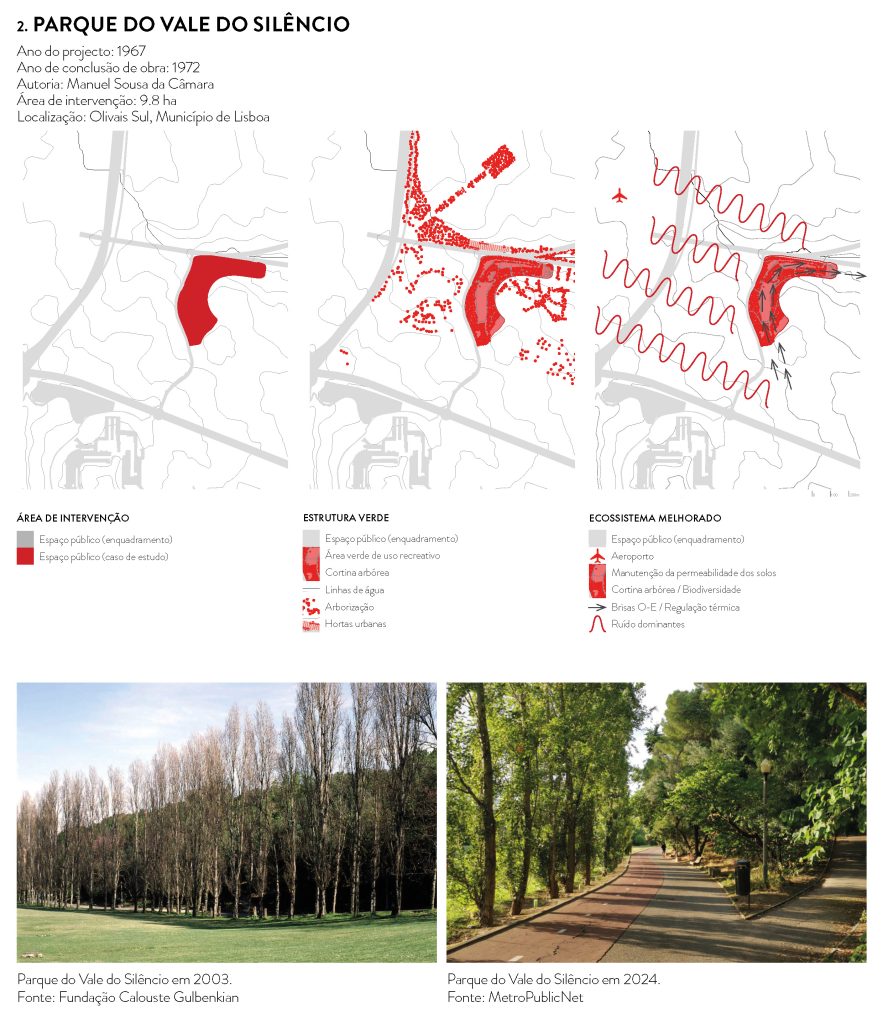

Parque do Vale do Silêncio [Valley of Silence Park]

The Parque do Vale do Silêncio, which mobilized a design team including landscape architects Manuel de Sousa da Câmara and Edgar Fontes, was conceived after the Olivais urbanization plan was drafted (1966). The Park was planned with a multifunctional perspective, providing various ecosystem services to residents of adjacent areas, namely: acting as a buffer for fumes, noise and odours from existing industrial activities by the river (where Parque das Nações is currently located), and the airport (CUNHA, 2015); (re)establishing contact for residents with green areas, and supporting the schools planned at its edge; and saving water resources and maintenance, namely by sowing a dryland meadow in the central clearing (Figure 3). All of this was to be achieved by particularly careful grading and a planting plan using native species, placed according to ecological suitability, topography, and sun exposure (CÂMARA, 2021).

The enhanced ecosystem

The ‘Valley of Silence’ toponym comes from the initial intention to give the Olivais [Olive Grove] neighbourhood with a park where silence and contact with nature were its most important qualities (CASTEL-BRANCO in CÂMARA, 2021: 136). The design options dictated that the valley be protected from road, industrial and airport infrastructure to shield it from noise and pollution. This was achieved by grading, which accentuated the morphological configuration of the valley. In turn, the mostly native planting plan, by the landscape architect Sousa da Câmara (CÂMARA, 2018), accentuates the valley shape with a biodiverse, dense edge that protects it from the prevailing winds, favouring the west-east breezes, and the resulting thermal regulation of the site. The meadow in the central clearing is a sizeable permeable area, where rainwater can accumulate and seep in. The quality of its design, and the relevance of its functions and uses, made the Vale do Silêncio Park a reference in the city, and added another ‘section‘ to the network of ecological corridors in Lisbon’s green zone. More recently, the Lisbon bike path network integrated a route across the park.

Figure 3 – Interpretative summary of the Vale do Silêncio Park case

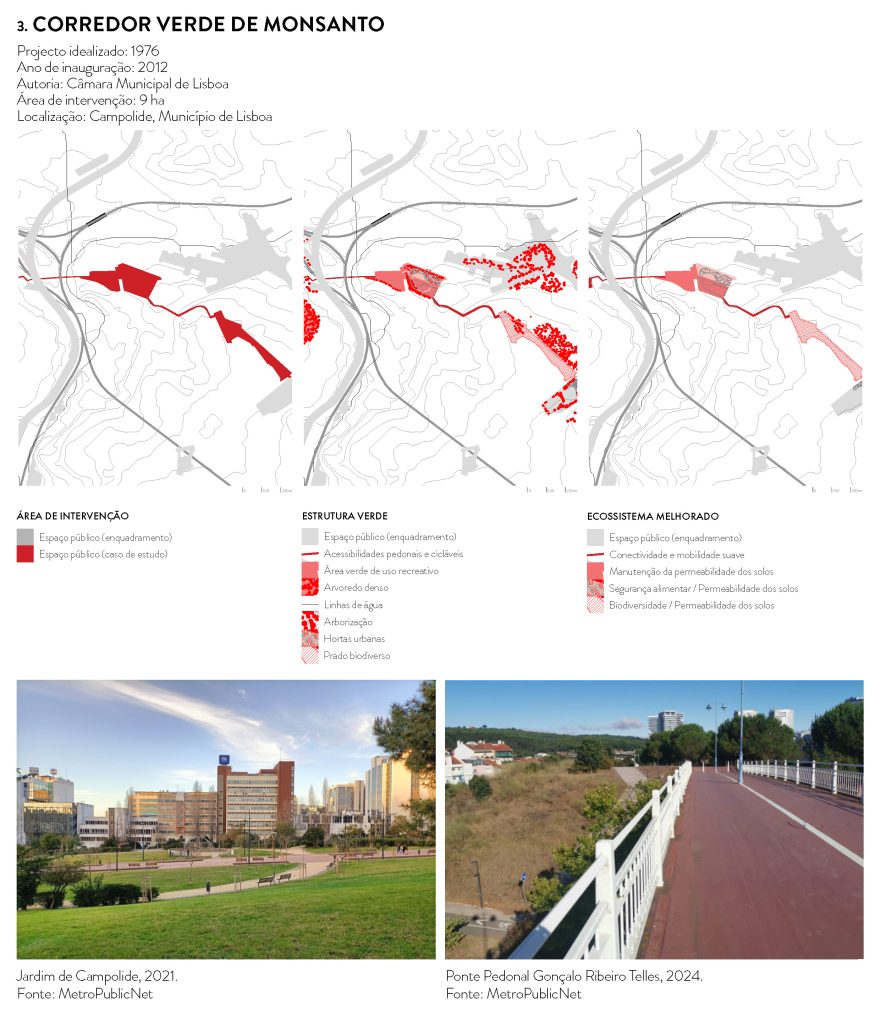

Corredor Verde de Monsanto [Monsanto Green Corridor]

The Monsanto Green Corridor, conceived and designed by Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles (TELLES, 1997), evokes the above principles of ecological continuity by linking the Monsanto Forest Park to the Tagus River through several green spaces (Figure 4). It was completed in 2020 with the creation of new public spaces including cycle and pedestrian bridges, gardens, vegetable gardens, fields, a playground, skate park, viewpoint and several terraces (BORGES, 2012).

The timeline was as follows: in 2002, the Green Corridor incorporated the Amnesty International Garden, which is divided into urban agriculture plots, grassland meadows and a series of recreational facilities serving the population of the Parish of Campolide. In 2009, the Urban Park of Quinta do Zé Pinto was incorporated and in 2010, the overpass to Avenida Calouste Gulbenkian and the cycle path on Avenida General Correia Barreto, providing access to the Calhau park, in Monsanto. In 2012, the biodiverse meadow was created in the area adjacent to the Palácio da Justiça [Palace of Justice] (SANTOS et al, 2025).

The enhanced ecosystem

Each of the above public spaces represents a series of ecological theory stepping stones (FORMAN, 2014) that implement the Monsanto Green Corridor in various types of public space. The measures, financed using public funding via the Lisbon City Council and Juntas de Freguesia [Parish Councils], apply the concept of the green corridor and ecological connectivity in their most literal sense. The projects are located essentially in headwater system areas, where maximising permeable zones for seepage is particularly important. On the other hand, the introduction of urban gardens references the self-sufficiency and food security of the population in its vicinity. The pioneering introduction of biodiverse meadow in Lisbon also reinforces its ecological quality due to the variety of dryland grass and associated fauna. These are low maintenance and adapted to the water and bioclimatic conditions of the site.

It is also important to stress the importance of integrating connectivity and accessibility by providing easy pedestrian mobility along the various public spaces of the Corridor to establish links between challenging topographic and infrastructural elements. In particular, we highlight the cycle and pedestrian bridges on Avenida Calouste Gulbenkian and Rua Marquês de Fronteira.

Figure 4 – Interpretative summary of the Monsanto Green Corridor case

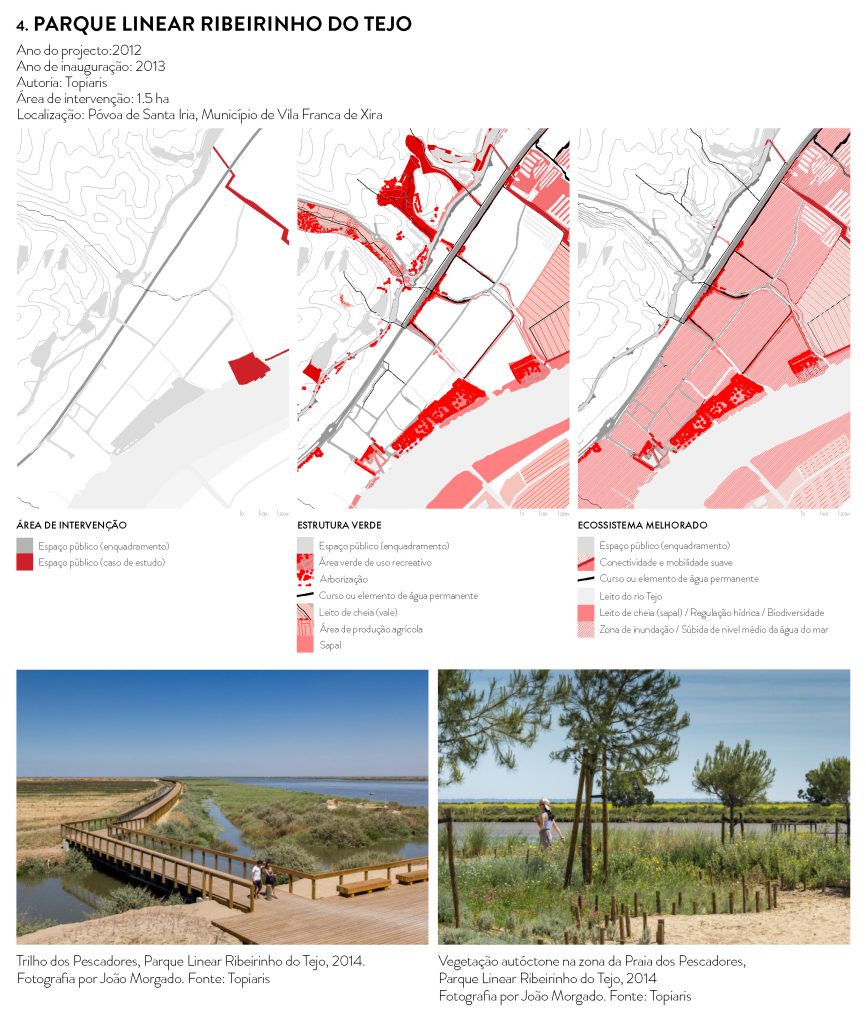

3.4 Parque Linear Ribeirinho do Tejo [Tagus Linear Park]

The Tagus Linear Park appeared following the expropriation of industrial land on the banks of the Tagus, and the environmental recovery strategy of the river front of the Municipality of Vila Franca de Xira. It improved access and public use of the river banks, which are not only a scenic landmark, but also an area of exceptional biodiversity.

The park, designed by the Topiaris landscape architecture studio, combines two distinct spaces: A multifunctional area, Praia dos Pescadores, located in an old sand deposit by the river; and a second area, adjacent to the first one, consisting of six kilometres of pedestrian paths on the dyke separating the marsh from the agricultural land, and connecting to the pre-existing agricultural dirt paths. In Praia dos Pescadores, the sand was maintained as the base substrate, on which dense vegetation of native species adapted to the saltiness and the sea air from the river took root. There are also accommodation areas, sports fields, and catering infrastructures here. The paths between Praia and the adjacent agricultural and natural areas in the estuary were built as an elevated wooden walkway, that includes rest areas, and an area dedicated to birdwatching (Figure 5) (TOPIARIS, 2010-2024).

The enhanced ecosystem

The principles of ecological design are represented in this project in the lightness of the design options and materials (inert and living) applied. The Tagus Linear Park has become a reference, as it capitalises on the post-industrial remains of the place while establishing a platform for access to and enjoyment of the Tagus River. The walkway over the dyke made known the unique landscape of the Tagus marshlands, through the possibility of ease of mobility for pedestrians and cyclists, offering a public space that is integrated into the marsh ecosystem and its tidal dynamics. The entire area is responsive to hydrological dynamics, even in a flood scenario. Biodiversity is highlighted here, both through the choice of planted species, and by the proximity to the extensive wetland of the islands in the Tagus river.

Figure 5 – Interpretative summary of the case of Parque Linear Ribeirinho do Tejo

4. Culture in ecology

Today ecology is culturally valued, which is not the same as saying that there is culture in ecology. As André Barata states, the current planetary crisis (economic, social, climate, environmental, …) requires a paradigmatic “metamorphosis” through small contagions and contaminations, which determine a trend, where everything must be thought of from an ecological point of view, forcing us to put relationships first: “a convivial relationship, a relationship of environmental diversity; but also cultural, of ways of seeing time, space and places” (RIOS, 2022: 13, BARATA, 2022). However, if the ecological-based thinking evidenced in the discipline of Landscape Architecture responds to this challenge, it is important for it to be shared with other disciplines, as well as civil society.

Many people today argue that in order to tackle increasingly imminent global crises, communities need to transition to holistic design approaches as opposed to unique solutions or solely technological corrections of a particular parameter (a lesson in systemic thinking first explained in the 1972 “Limits to Growth” report). It is true that technical developments have allowed incredible and extremely ingenious advances that should be valued, harnessed, and not ignored. However, we need to enrich current knowledge and practice by moving towards a new paradigm that calls for projects that promote the establishment of ecological, cultural and aesthetic values, placing the focus on convincing relationships, experimental or otherwise, between all elements, living or material. Inclusive projects of complexity, accepting uncertainty and change, which also consider subjective aesthetic and cultural knowledge along with objective scientific and technical skills. We must therefore promote an ecology-based culture that can draw on decades of experience and knowledge. A process that involves investing in the development of an agenda of values rooted in cultural, aesthetic and ecological principles, moving beyond the strictly academic sphere.

The design of public space offers the possibility of being thought out based on an ecological category, thus reinforcing the role of design practice in re-establishing old relationships or fostering new ones. This is one proposal of the research project “MetroPublicNet” (SANTOS, 2020), which by highlighting the incremental process of public space projects over the last 25 years, suggests the conceptual basis of a metropolitan network of public spaces as an operational tool for making political decisions that can respond to the main challenges of today. A system of broadly supported public spaces that, by incorporating ecology-based thinking, embrace the landscape so that the (as yet) disproportionate anxiety about its control is calmed and balanced by projects that are open to uncertainty, continuously monitored, consequential, safe and inclusive.

Bibliography

ANDRESEN, Teresa – Francisco Caldeira Cabral. Surrey, United Kingdom: LDT monographs, 2011.

ANDRESEN, Teresa (coord.) – Do Estádio Nacional ao Jardim Gulbenkian. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2003.

BARATA, André – Para viver em qualquer mundo. Nós, os lugares e as coisas. Lisboa: Documenta, 2022.

BORGES, Liliana 2012 – Corredor Verde de Monsanto finalizado três décadas depois, Público online. 14/12/2012. Disponível em:

https://www.publico.pt/2012/12/14/local/noticia/corredor-verde-de-monsanto-finalizado-tres-decadas-depois-1577501 [Consult. 24/07/2024].

BROWN, Rebekah R.; KEATH, Nina; WONG, T. – Transitioning to Water Sensitive Cities: Historical, Current and Future Transition States. 11th International Conference on Urban Drainage. Edinburgh, Scotland, 2008, p. 1-10.

CABRAL, Francisco Caldeira – A Paisagem como Expressão de Cultura. Brotéria – revista de cultura, Vol. LXXXIV, 1967, p. 12.

CÂMARA, Teresa Bettencout da – Parque do Vale do Silêncio [Online]. Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico (SIPA), 2018. Disponível em: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/SIPA.aspx?id=26714 [Consult. 24/07/2024].

CÂMARA, Teresa Bettencout da – Espaço Público de Lisboa. Plano, projeto e obra da primeira geração de arquitetos paisagistas (1950-1970). Lisboa, Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 2021.

CUNHA, Andreia – Análise e Interpretação de Obras de Arquitectura Paisagista de Manuel de Sousa da Câmara (1929-1992). Lisboa: Instituto Superior de Agronomia, 2015. Dissertação de mestrado em Arquitectura Paisagista,

DINIZ, Victor Beiramar – Habitar o espaço público: reflexão sobre quatro exemplos. Estudo Prévio 22. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2023, p. 116-125

FARINHA-MARQUES, Paulo – Nature-based solutions in the teaching of landscape design by Manuel de Sousa da Câmara. In: MATOS SILVA, Maria; CASTEL-BRANCO, Cristina; RIBEIRO, Luís Paulo; NUNES, João Ferreira; ANDRESEN, Teresa (eds.) – Portuguese Landscape Architecture Education, Heritage and Research: 80 Years of History. London: Taylor & Francis, 2024, p. 156-163.

FORMAN, Richard T. T. – Urban Ecology: Science of Cities. New York, United States of America: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

JACKSON, John Brinckerhoff – Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986.

MATOS SILVA, Maria – Public space design for flooding: Facing the challenges presented by climate change adaptation. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, Spain, 2016. Tese de doutoramento.

MATOS SILVA, Maria – 2024. Three principles of ecological thinking for an interpretation of Portuguese Landscape Architecture education, heritage, and research. MATOS SILVA, Maria; CASTEL-BRANCO, Cristina; RIBEIRO, Luís Paulo; NUNES, João Ferreira; ANDRESEN, Teresa (eds.) – Portuguese Landscape Architecture Education, Heritage and Research: 80 Years of History. London: Taylor & Francis, 2024, p. 1-5.

MATOS SILVA, Maria; CASTEL-BRANCO, Cristina; RIBEIRO, Luís Paulo; NUNES, João Ferreira; ANDRESEN, Teresa (eds.) – Portuguese Landscape Architecture Education, Heritage and Research: 80 Years of History. London: Taylor & Francis, 2024.

NUNES, João et al – PROAP – Concursos Perdidos – Lost Competitions (Arquitectura Paisagista). s.l.: Blau, 2011.

RIOS, Pedro – Entrevista a a André Barata. Jornal Publico – P2, 07/08/2022.

SANTOS, João Rafael; BEJA DA COSTA, Ana – Espaço Público. Área Metropolitana de Lisboa. Projectos de qualificação do território [1998 – 2023] – As infraestruturas Verdes e Azuis. Lisboa: Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa, CIAUD & Área Metropolitana de Lisboa, 2023.

SANTOS, João Rafael; MATOS SILVA, Maria et al – MetroPublicNet – Building the foundations of a Metropolitan Public Space Network to support the robust, low-carbon and cohesive city: Projects, lessons and prospects in Lisbon. Lisboa, 2020. Projeto FCT PTDC/ART-DAQ/0919/2020.

SANTOS, João Rafael; MATOS SILVA, Maria; BEJA DA COSTA, Ana – Towards a Metropolitan Public Space Network: lessons, projects and prospects from Lisbon. London: Routledge, 2024.

SILVA, Raquel Henriques da – Lisboa de Frederico Ressano Garcia 1874-1909. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Camara Municipal de Lisboa, 1989.

SOLDADO, C. – Kongjian Yu quer transformar as cidades em esponjas, uma solução para cheias e secas. Público 10/06/2024. Disponível em: https://www.publico.pt/2024/06/10/azul/noticia/kongjian-yu-quer-transformar-cidades-esponjas-solucao-cheias-secas-2093378 [Consult. 30/10/2024].

TELLES, Gonçalo Ribeiro – Para Além da Revolução. Lisboa, Edições Salamandra, 1985.

TELLES, Gonçalo Ribeiro – Plano Verde de Lisboa. Lisboa, Edições Colibri, 1997.

TOPIARIS. 2010-2024. TAGUS LINEAR PARK [Online]. Disponível em: https://www.topiaris.com/works/tagus-linear-park [Consult. 25/07/2024].

VIGANÒ, Paola; FABIAN, Lorenzo; SECCHI, Bernado – Water and Asphalt: The Project of Isotropy. Zurique: Park Books, 2016.

Notes

1. Drawing a parallel with the “Urban Water Transitions Framework” (BROWN; KEATH; WONG, 2008: 1-10).

2. Excerpt from the recent interview with Kongjian Yu in the Jornal Publico newspaper: “When asked about the Lisbon drainage plan, which involves an investment of 250 million euros and, among other things, opening two large tunnels, the landscape architect laughed aloud. ‘This is the business as usual model. It won’t solve the problem’, he says.” (SOLDADO, 2024).

3. How the lines of research specifically related to landscape design, planning and management became consolidated is revealed throughout the chapters. There is a clear, meshed connection between educational and professional activities. This also explains why Portuguese Landscape Architecture is at the forefront of the discipline’s specific theory and methods, particularly in the areas of sustainability, resilience and interdisciplinarity as applied to the architecture of complex landscape systems.

4. As Farinha Marques explains in his article “Nature-based solutions in the teaching of landscape design by Manuel de Sousa da Câmara”, concepts currently fashionable in sustainability jargon, such as “nature-based solutions” or “ecosystem services”, have existed ever since the Landscape Architecture course was introduced to the Portuguese academic circuit by Francisco Caldeira Cabral in 1942 (FARINHA-MARQUES, 2024).

5. The principle that became widespread in Portugal from the 1940s onwards thanks to Francisco Caldeira Cabral which is that: “the continuous system of natural occurrences that support wildlife and the preservation of genetic potential and which contributes to the equilibrium and stability of the land” was only legally defined after the Democratic Revolution, namely in the Basic Law of the Environment [ Lei de Bases do Ambiente] No. 11/87 of 7 April.

6. “Portugal can boast of having excellent garden designers in the 19th century – along with other countries such as Germany, England and Belgium – but Cabral never assumed this role. He acknowledged having learned gardening and horticulture techniques from these designers, but said they had lost “the essential idea of form.” Cabral was a pioneer, not a follower” ANDRESEN, 2001)