Delia Ioana Sloneanu

sloneanu.delia@gmail.com

Architect and PhD student at the Department of Architecture of Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (Da/UAL), Portugal. CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, Portugal

To cite this article:

SLONEANU, Delia – The third bank of the river: residence for the Portugal embassy in Brasilia. Estudo Prévio 25. Lisbon: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, December 2024, p. 19-52. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/25.2

Received on July 30, 2024, and accepted for publication on September 30, 2024.Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The third bank of the river: residence for the Portuguese embassy in Brasilia

Abstract

This article aims to investigate the Competition for the Residence of the Portuguese Embassy in Brasília, organized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs between 1995 and 1996, in which Ricardo Bak Gordon (1967-) and Carlos Vilela Lúcio (1967-) placed first. To this end, the research goes back in time, looking at the historical events that led to this competition. Subsequent developments will also be analysed, focusing on the figure of Ricardo Bak Gordon, from his trip to Brazil and his relationship with Paulo Mendes da Rocha, to the need to develop a second project of reduced dimensions, years later. Essential for the development of the research, these three times – past, present, future – serve to illustrate a panorama much larger than the object of study, necessary for its understanding. Consequently, in the search for identity elements in Bak Gordon’s architecture, concepts such as crossing – physical and cultural – continuity, as permanence and awareness of distance in time, and in vitro representation, as a condition of porosity – physical and conceptual – that allows transparency, while preserving an image, will be explored.

Keywords: competition, embassy, Brazil, Portugal, modernism, Brasilia, third bank of the river

1. Introduction

Ricardo Bak Gordon (1967- ) is part of the group of Portuguese architects who stood out as “the 90s generation”, the most recent significant generation on the internationally renowned Portuguese architecture scene. At the start of his professional career, together with his then partner, Carlos Vilela Lúcio, he won first prize in the competition for the Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia in 1995. The project stands out because of its synthetic and original vision, which is characteristic of the late twentieth century. It ushered in a new approach that did not seek to break with modernism, while at the same time distancing itself from the view of modernism as a style.

While the first part of the article discusses the competition and the historical context that defined it, as well as focusing on the winning project, the second part is more personal and biographical and examines the circumstances surrounding the second project. The theoretical metaphor that connects the two parts serves as basis and reference for the study: João Guimarães Rosa’s concept of the “third bank of the river” as a place suspended between the here and there, a new margin from an architectural point of view. This study intends to demonstrate how Ricardo Bak Gordon’s architectural thinking fosters the methodological basis used to respond to a specific demand, as well as the tools used to access this particular universe of restlessness, “downstream, upstream, across the river” (ROSA, 1962: 110). The research question is the following:

When we think of crossing as displacement between two points, can we understand the perception of the route as the conception of a third internal point, crossed by the crossing? Does this third bank, perceived and constructed, emerge as a possible element of identity?

In the light of this question, by focusing on the figure of architect Ricardo Bak Gordon, the article moves between historical accounts, biographical aspects and analysis of the creative process, based on the understanding that these areas constantly influence and determine each other. This triad, as well as the flows of these three moments in time – past, present, future – converge within the third bank. This creates the multiple circumstances that condition architectural life and production and which are deeply interconnected.

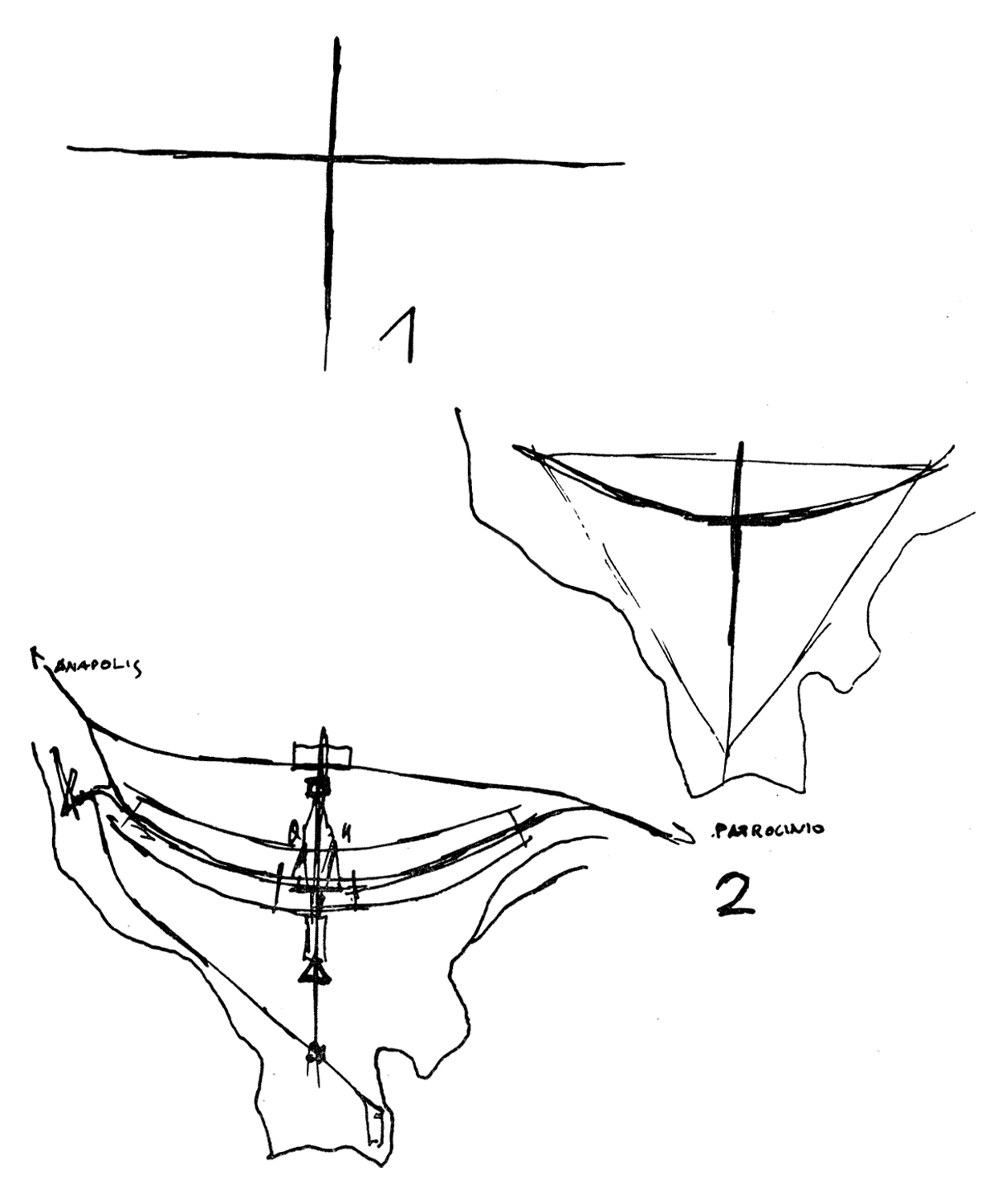

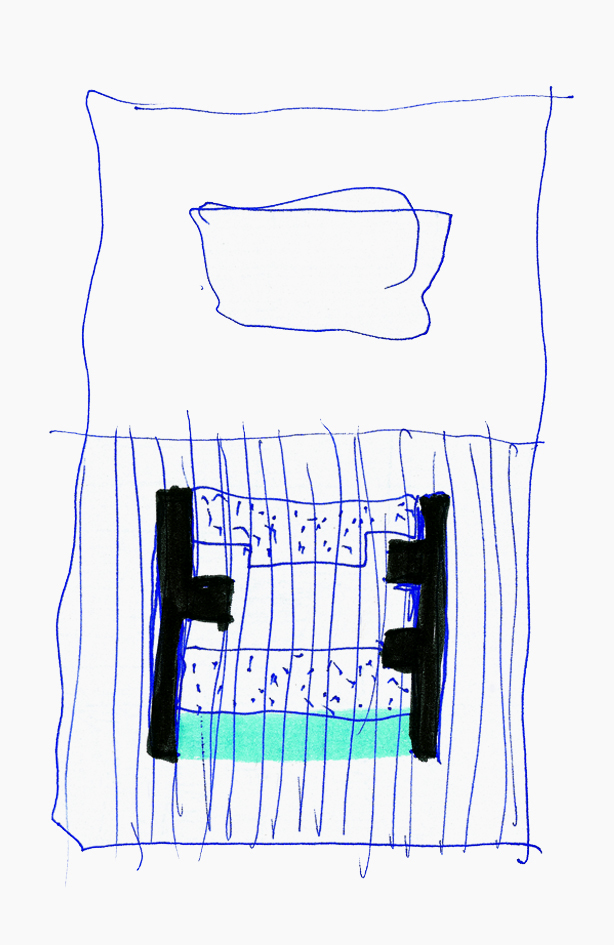

Figure 1 – Sketch of the Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia made by Ricardo Bak Gordon during the research interview. June 2024 (Source: Personal communication of the author).

State of the Art

For this research, the state of the art brings together books, magazines, articles, lectures, and interviews which provide a theoretical and documentary basis for the analyzed projects. For the Embassies of Portugal in Brazil prior to the competition being researched, texts and images were consulted in the magazine Arquitectura from 1974, the “Catálogo da Exposição Raul Chorão Ramalho Arquitecto” (RIBEIRO, 1977), and the book “Três Embaixadas Portuguesas: Londres, Madrid, Rio de Janeiro” (CARNEIRO, 2021). For the competition for the Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia in 1995, the entire bibliography on the project was collected. As the research examines closely the concepts behind these projects by focusing on the figure of the architect Ricardo Bak Gordon, in addition to monographs published in 2005, 2009, 2021 and numerous lectures, an interview with the architect was conducted.

Finally, the short story “A Terceira Margem do Rio” (ROSA, 1962) is a literary work whose narrative permeates this study. It is one of the most influential works by the author João Guimarães Rosa and is considered a masterpiece of Brazilian literature. Rosa adopts a regionalist but also universal tone to pose the major dilemmas of human existence. The story recounts the curious tale of a father who suddenly decides to abandon his family and society altogether, to live in a small canoe, between the banks of an immense river. The concept of the third bank refers to an existence halfway in-between, one that ends up creating a third place of acting, an internal gold mine.

Figure 2 – Illustration for “A Terceira Margem do Rio” – João Guimarães Rosa and Luís Jardim. 1962 (Source: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Terceira_Margem_do_Rio [Consulted April 2024]).

2. Context

The Rio embassy

The choice of situation in time for the object of study begins with the construction of the Embassy of Portugal in Rio de Janeiro, capital of the then Republic of the United States of Brazil (1889-1968). In 1922, on the occasion of the International Exhibition of Rio de Janeiro commemorating the Centenary of Brazilian Independence, the palace on Rua São Clemente was purchased, in order to provide a suitable location in the capital for the diplomatic mission. The first Embassy of Portugal operated there for 25 years. After World War II, because of the difficult diplomatic relations between the two countries – on the one hand, the Salazar regime, on the other, the transition from the Brazilian “Estado Novo” to democratic opening following the deposition of Getúlio Vargas by the military in 1945 – there was an immediate need to renovate the palace housing the Embassy. This was a lengthy process that took 15 years and 5 projects before the works were completed in 1961, when the country’s capital was relocated to Brasília, outside the Rio – São Paulo axis.

The commission was first awarded to the Brazilian firm Severo & Villares, the former Escritório Técnico Ramos de Azevedo, in 1946. As the proposal proved to be too expensive, in 1947, attention shifted, this time to two well-known Portuguese technicians: the engineer Fernando Jácome de Castro and the architect Guilherme Rebelo de Andrade, who had previously worked on the renovation of the Madrid Embassy. The project was awarded to the Rebelo de Andrade brothers’ firm, which developed 4 versions of the project over 14 years, going through changes of presidents and ambassadors, until the completion of the works in 1961.

Figure 3 – Embassy of Portugal Project in Rio de Janeiro, “South Façade”, Drawing No. 6. 1954 (Source: CARNEIRO, Luis – Três Embaixadas Portuguesas: London, Madrid and Rio de Janeiro – Arquitectos Irmãos Rebelo de Andrade. 2021: 190).

A new capital

In 1955, Juscelino Kubitschek ran for President of the Republic with the promise of an ambitious project called Plano de Metas [Plan of Goals], intended to develop various sectors in Brazil, and culminating in the construction of a new capital. To this end, a place in the Central Plateau was geometrically selected, in an area considered the epicentre of Brazil, a tabula rasa equidistant from the country’s borders. The following year, Juscelino Kubitschek was elected, and the construction of Brasília began, only to be inaugurated less than four years later.

In 1956, in order to define the urban planning of the new Brazilian capital, a national competition was organized, called the Pilot Plan, a term coined by Le Corbusier. Out of the 26 projects submitted, the architect and urban planner Lúcio Costa was the winner. What caught the jury’s attention was his rhetoric, which combined the ethical, aesthetic, and historical values of the creation of a new capital while representing an expression of the new architecture of the time. Very persuasively, Costa presented a very synthesized 24-page justificatory report, and a single hand-drawn pilot plan, promising to provide further details of the project if the jury expressed interest. This is how an idea of a city which we now recognise as the greatest example of modernism on an urban scale came into being.

Figure 4 – Brasilia Pilot Plan, Lúcio Costa Report. 1956 (Source: http://doc.brazilia.jor.br/plano-piloto-Brasilia/relatorio-Lucio-Costa.shtml [Consulted May 2024]).

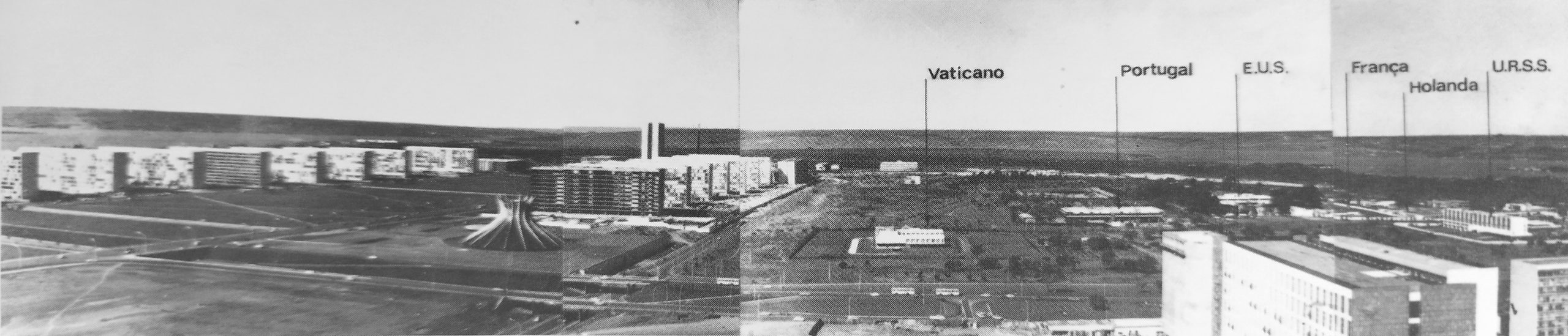

Figure 5 – Brasilia Magazine, No. 3, Fundo NOVACAP, held at the Public Archive of the Federal District. 1957 (Source: https://www.arquivopublico.df.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NOV-D-4-2-Z-0001-1d.pdf [Consulted May 2024]).

In 1960, Brazil inaugurated the new capital, although many people doubted its success. When the federal capital was transferred to Brasilia, all the embassies were relocated to the new sector located in Asa Sul [South Wing], which was destined for diplomatic missions from other countries. Portugal, which was about to complete the works that had been ongoing in Rio for 14 years, was now under pressure from the Brazilian government to move to the new capital. The first half of the 1960s marked a turning point in the turbulent external relations between the two countries. On the one hand, it marks the beginning of the end of the Portuguese colonial empire, with the beginning of the war in Africa, the invasion of Goa and increased internal protests against the Salazar regime and emigration, and on the other, the establishment of the military dictatorship, which ruled Brazil for the following 21 years.

The Embassy of Brasilia

In an attempt to gain time and minimize tensions, while facing pressure from the Brazilian Government to move the Embassy to the new capital, a visit to Brasilia was conducted. It ended with the inauguration of a monument to Prince Henry the Navigator in 1960. This was the reason for choosing the site of the future Embassy in lot 2 of Avenida das Nações with the official transfer of the Itamaraty to Brasília. Between 1971 and 1973, the architect Raul Chorão Ramalho, in collaboration with the architect Leonel Clérigo, developed the entire project for the Embassy of Portugal. However, only the Chancellery and Praça de Portugal were built, while the Ambassador’s Residence, the employees’ quarters and the external arrangements were left out.

Figure 6 – Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, in lot 2 of Avenida das Nações. 1974 (Source: RIBEIRO, Rogério – Exposição Raul Chorão Ramalho, Arquitecto. 1977. 139).

Raul Chorão Ramalho (1914-2002) was a prominent figure in post-war Portuguese modernist architecture. His vast output spanned the Portuguese mainland, the Atlantic islands, Macau and Brazil. An active voice in the opposition to the Estado Novo Regime, he was a founding member of ICAT (Cultural, Art and Technical Initiatives) founded on 11 March 1947. He participated in the 1st National Congress of Architecture in 1948, and also in several editions of the Exposição Geral de Artes Plásticas [General Exhibition of Visual Arts]. Adopting an abstract approach, one that synthesises detail and choice of materials, his timeless work succeeded in crossing continents without losing coherence; “retrieving information and subtly incorporating notes from different cultures.” (RIBEIRO, 1977: 22) Perhaps the most striking characteristic of Chorão Ramalho’s architecture, which is clear in his public works, is its urban quality. The projects are either very well integrated into the urban network in which they stand, or they themselves create urbanity. Reflecting an ethical quality in his architecture, the facilities designed by Chorão Ramalho carefully match the requirements of the programs, and are based on a deep knowledge of techniques and materials. Quality and rigour are present in all scales, from insertion into the city to the interior design and decoration.

In his notes on the Preliminary project, the architect states that he intended to achieve three main objectives. First, the monumentality required of the Portuguese diplomatic mission in Brazil; second, austerity of composition, achieved by prioritizing structural elements and sober materials; and last but not least, to portray the various layers of meaning of its insertion into that context:

“…we would also like the architectural image of the building to reflect (…) the idea of a “shelter” or porch offering protection from an exterior climate and from the intense luminosity, and also the idea of a welcoming, open, familiar shelter without borders with the City.” (RIBEIRO, 1977: 137)

Figure 7 – Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Raul Chorão Ramalho. 1972-1976 (Source: Architecture, no.130, May 1977: 24).

The spatiality of the Chancellery building reveals a dominant structural design. The parallelepiped volume is achieved by a rationalist distribution of pillars, overhanging slabs, balconies, grilles over open spaces, stairways, with closing frames shaded by flaps and venetian blinds. Works of art signed by Portuguese artists are displayed throughout the interior, with tile panels, bas-reliefs in concrete and tapestries, as well as in the exterior space, with sculptures and pavement drawings. The Residence building, which is less austere, spreads out in conjugated volumes around the outdoor public spaces, considering Praça de Portugal as a pre-existence. On a scale more suitable for a residence, the transition between the interior spaces and the gardens is made via covered shaded areas, with a discreet enclosure that ensures the continuity of the green space in which the building stands.

Figure 8 – Chancellery of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Raul Chorão Ramalho. 1972-1976 (Source: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/SIPA.aspx?id=14191 [Consult. May 2024]).

Figure 9 – Unbuilt residence of the Portuguese Embassy in Brasilia, Raul Chorão Ramalho. 1972-1976 (Source: Arquitectura, no.130, May 1977: p.28).

The Embassy program above all calls for the representation of a country, of a culture of departure inserted into the context of another country, within a culture of arrival. The project by Chorão Ramalho demonstrates his skill at incorporating a “Portuguese stately home” into Brasilia, a city-manifest of modernism (RIBEIRO, 1977: 32) in its most modern, international form. According to Victor Mestre, the fact that this entire opus was not built reveals the petty-mindedness of politicians, who did not seem to understand the political, social and cultural significance that a major building would have in future.

Figure 10 – Chancellery of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Raul Chorão Ramalho. 1972-1976 (Source: RIBEIRO, Rogério – Exposição Raul Chorão Ramalho, Arquitecto. 1977) 13-14).

3. The competition for the Embassy residence

In 1994, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to continue the construction of the Embassy residence, but not to resume the original project by Raul Chorão Ramalho and Leonel Clérigo. At the end of 1995, an international call for competition was organised – up to then the only architecture competition organised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for an Embassy in a foreign capital (later, in 1998, a second was launched for the Chancellery and residence of the Portuguese Embassy in Berlin).

The report accompanying the exhibition of the works, organized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, begins with notes on the objectives and program of the competition, and reveals the complexity of the challenge that the participants were facing. First, its location in the city envisioned by Lúcio Costa is defined as the inspiration for a contemporary language – one that is current while also “embodying symbolic and emblematic thinking” (Fernandes, 1995: 2). The language of the Residence should form the link between the original language of the Chancellery designed by Raul Chorão Ramalho in 1973 and the Praça de Portugal. Like the Chancellery, the new building would also have the challenge of finding solutions to mitigate the effects of Brasilia’s extremely dry climate. Another important aspect to be considered was the relationship with the limitations of the existing context, where the balance between separation from and connection to the existing Chancellery and the proposed residence is highlighted. Finally, observations on programmatic distribution define four main areas: a reception area, a family housing area, a guest area and a service area. Forty-four teams took part in the competition, resulting in three awards and two honourable mentions. First, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio; second, Óscar da Silva Lopes and Nuno Francisco Magalhães Pinto; and third, Anton Schweighofer and Pedro George. The first honourable mention was for João Luís Carrilho da Graça, and the second for Angêlica Baptista da Silva.

The jury identified three main categories of solutions. One where the residence is centred around one or more courtyards (into which the volume of Chorão Ramalho‘s unbuilt residence is also inscribed); one in which relatively simple volumes are combined to create tiered spaces which interact in a more or less complex way with the existing Chancellery; and a third, with evident original features, which delimits space using a covering structure, thus creating a balanced bioclimatic design that provides shade and transparency.

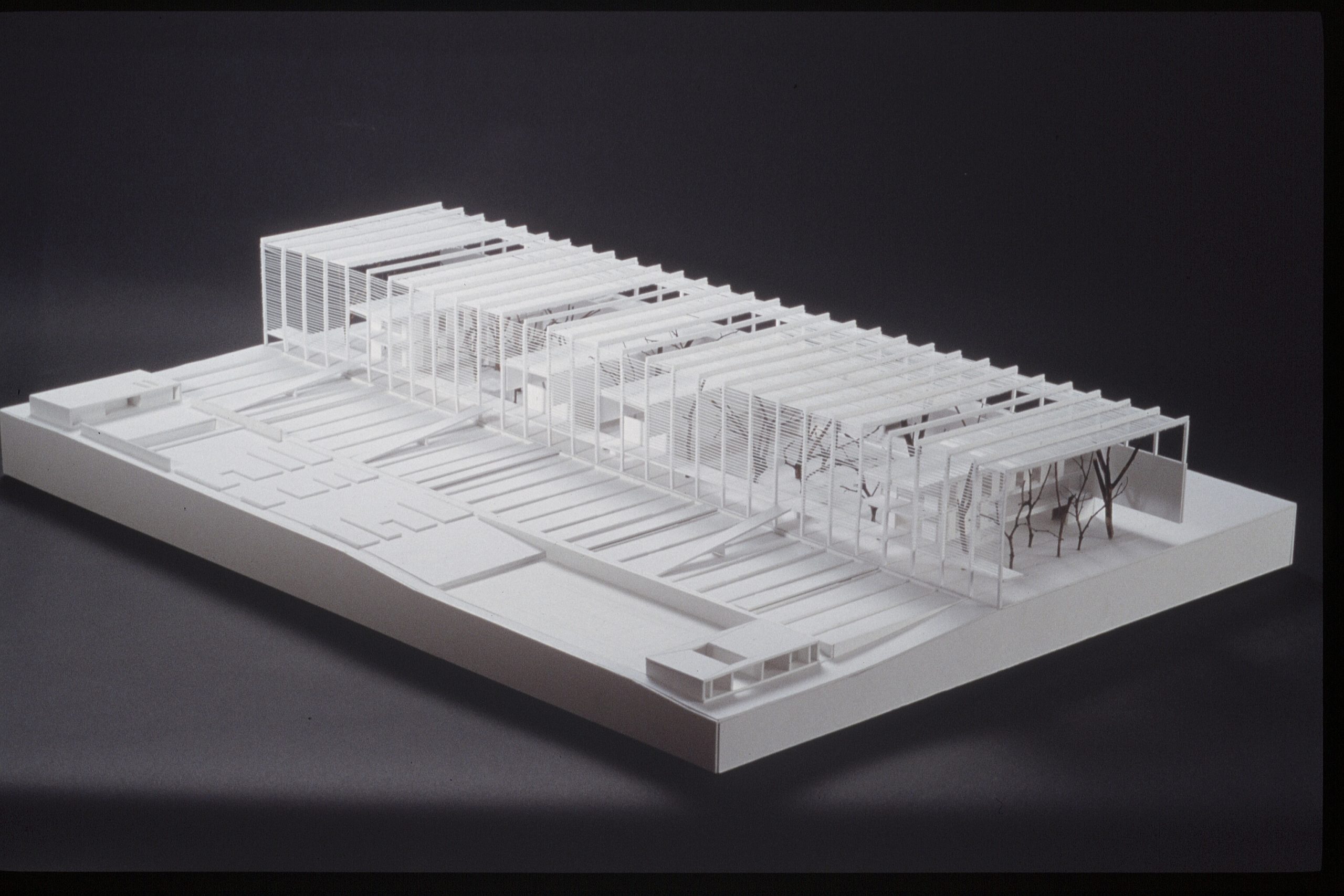

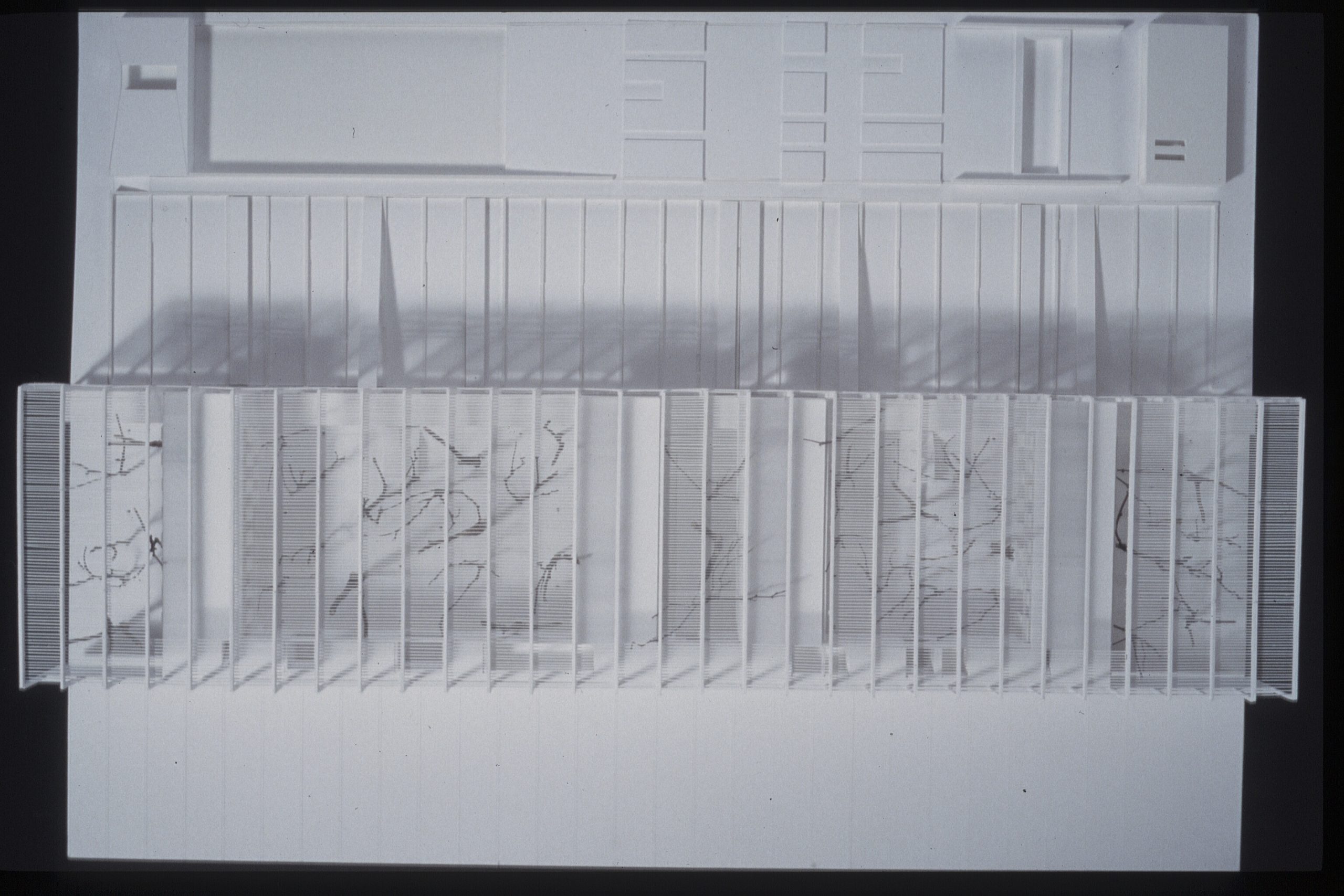

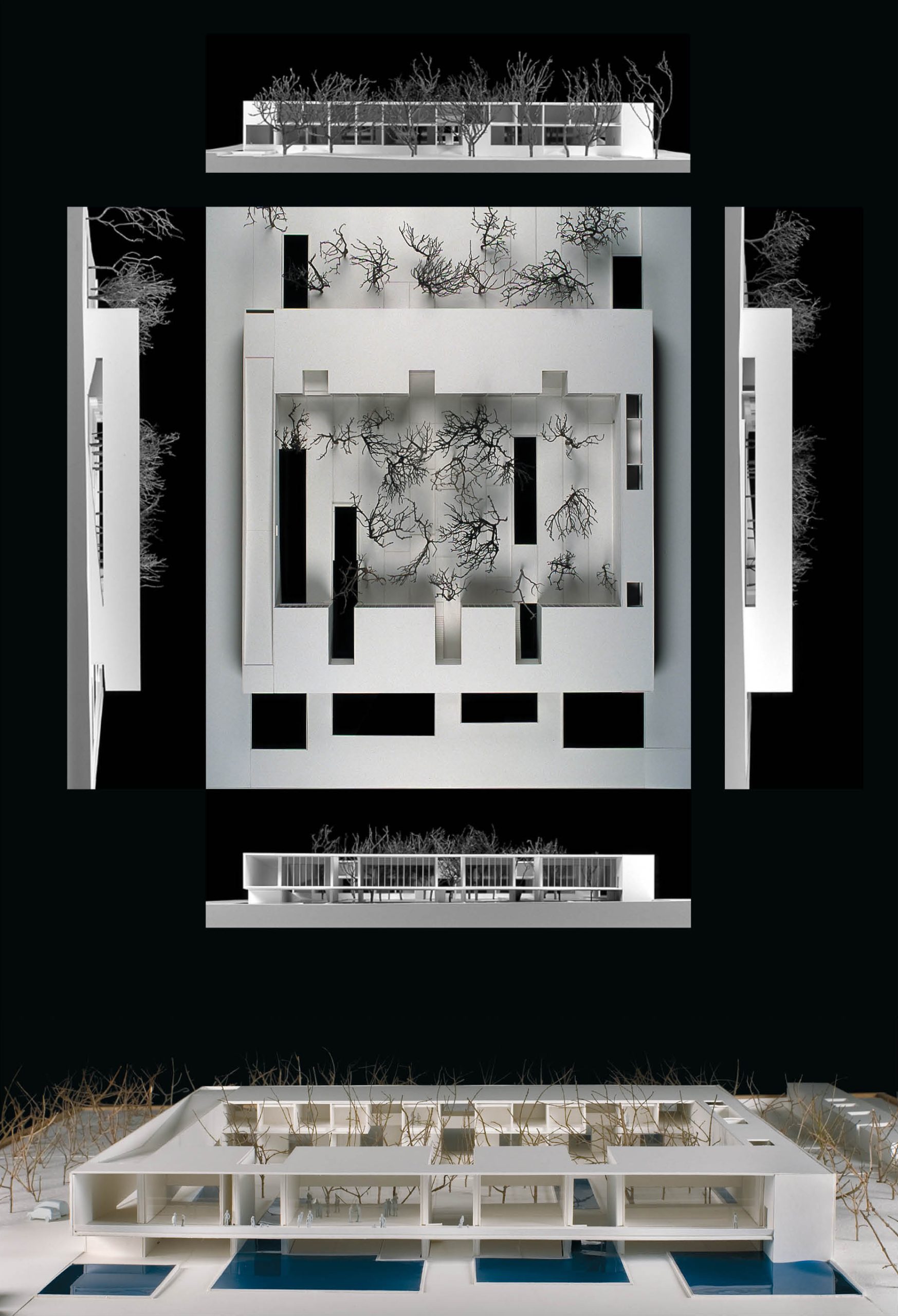

Figure 11 – Model for the competition for the residence of the Portuguese Embassy in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

The winning proposal by Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio not only responded to all the requirements by balancing the multiplicity of constraints, but was able to do so in a completely original way. They created a kind of in vitro representation, as described by Ricardo Carvalho when discussing the two competitions for the Embassies in Brasilia and Berlin:

“At the basis of these proposals is the in vitro genesis of Brasilia and Berlin, to which the response is the Chancellery and/or Residence program, as a representation, also in vitro, of an identity transported to another territory.” (CARVALHO, 2003: 58)

For Ricardo Bak Gordon, the only place where ideas arise is inside our head. They are then elaborated and investigated using the many tools architects have at their disposal. During the interview for this article, when asked about how the idea for this competition came about, he recalled those initial moments:

“(…) there was a kind of epiphany on the day we looked at those parallelepiped blocks, (…) placed on that board, which was a type of design of Lúcio Costa’s plan, and we thought: how about if one of them, instead of being made of concrete, was made of forest. This became the starting point for the possibility of a building where one could live right there in the middle (…) and that culture was basically this possibility of existing and living within that very forest.” (Interview with BAK GORDON, 2024)

Figure 12 – Model for the competition for the residence of the Portuguese Embassy in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

To answer the questions posed by the program and the location, the architects devised a parallelepiped volume, which resembles the architectural landscape of Brasilia, while striving for another dimension, with a critical attitude towards the city. Extending between the two sides of the plot, the façade facing the Praça de Portugal performs the role of representation, through a silkscreen panel with a mosaic of eyes of Portuguese cultural icons, which resembles a filmstrip. In the words of its authors, this

“is not intended to be historical or symbolic but merely human, simultaneously disturbing and abstract, able to “hypnotize” and relegate the materiality of the façade to the background.” (Bak Gordon and Vilela Lucio in FERNANDES, 1955: 6)

Figure 13 – Façade of the residence of the Portuguese Embassy in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Capa da Revista Arquitectos, no.155-156, Lisbon, 1996).

This image recalls a project from another competition that took place in 1992. This is Herzog & De Meuron’s proposal for the two Jussieu Libraries in Paris. The main façade, in transparent glass screen-printed with the faces of writers and academics, symbolizes the essence of the project – the relationship between people and texts. Herzog & de Meuron had been using stone or screen-printed glass façades since the late 1980s in projects that were disseminated widely in the El Croquis Magazine. These had an impact on the world architectural scene in the late 20th century. Bak Gordon and Vilela Lúcio experimented the façade in silkscreen stone for a previous competition, for the renovation of the Banhos de São Paulo, the current headquarters of the Order of Architects in Lisbon, when they received honourable mention in 1991.

In the Residence for the Embassy, this façade acquires dimensions that are worthy of representing a country. By using a feature of modern Brazilian architecture – an infinite floor under an open span – the panel of the west façade is suspended in air, above the polished Portuguese stone sidewalk. The other sides of the parallelepiped, sometimes transparent, sometimes translucent, filter and absorb the sun, creating a greenhouse with a regulated environment. Together with the water mirrors that surround the building, these function as a hygrometric resource to offset the dry climate. Inside this greenhouse, there is lush vegetation recalling the Amazon rainforest, like a piece of landscape set in an artificial territory, a metaphor that creates an interior landscape. In the middle of this, overhead volumes seem to float, connected to each other – and to the structure of the casing – through metal walkways.

Figure 14 – Model for the competition for the Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 15 – Model for the competition for the Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 16 – Model for the competition for the Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

This was not the first time that part of a forest had been transported to and installed elsewhere. In Lisbon, the Portuguese have one of the best examples of this, a reference project worthy of mention. The Estufa Fria [Cold Greenhouse] is a project originally conceived of by the architect Raul Carapinha that was later rebuilt and expanded by Keil do Amaral. It is a park located in an old quarry, covered by wooden slats to protect the plants from extreme temperatures. When you visit this place, the intention behind Bak Gordon and Vilela Lúcio’s desire to create an environment with its own atmosphere becomes clear: it is a protected oasis in the middle of the city, where nature can flourish independently.

Figure 17 – Lisbon Estufa Fria. 2024 (Source: Photographs taken by the author).

Figure 18 – Lisbon Estufa Fria. 2024 (Source: Photographs taken by the author).

Therefore, the architects’ preoccupation with the phenomenological experience of the project they imagined is evident. To realise this, they juxtaposed antithetical elements in the very heart of the modernist city:

“The atmosphere of Brasília is no stranger to this moment of synthesis, an equation of two unknowns engaging with each other – Man/God, infinitely small/ infinitely large, impure/pure, artificial/natural. Lunar, sidereal, it transcends the presence of mankind, becoming more metaphysical than real, reminiscent of De Chirico.” (BAK GORDON; LÚCIO, 1995: 5)

These are the concerns that led to the atmosphere of this inner landscape created by lush vegetation, walkways and suspended volumes, where sunlight, always in motion, is captured and filtered by the façades of metal slats and reflected in the water mirrors. Having exhausted the modernist stylistic concerns, architecture seeks refuge in the senses, and strives to create a kind of mirage, a dream, like that “moment when our brain moves between wakefulness and sleep.” (Interview with BAK GORDON, 2024)

Moving on to a programmatic analysis, we observe four main functional areas separated into distinct volumes, elevated three to five metres above the pavement and connected by the system of crosswalks. On the ground, pedestrians and vehicles move freely, with pedestrians having right of way. They have the option of a more flowing path, a real promenade architecturale through the organism of the building. The volume of the family residence is the interface between the Chancellery and Praça de Portugal. Two façades, one transparent and the other opaque, balance the relationship between the private and public spheres. The laminar volume of services, attached to the west façade, houses at the bottom vertical accesses and a car park, while at the top it creates a bridge between the reception area and the volume of the housing. The volume of the guest area was situated in the southern part of the building as a refuge pavilion isolated in the midst of the vegetation.

Figure 19 – Layout of the Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio (Source: Revista 2G Bak Gordon, no. 64, Barcelona, 2012).

Figure 20 – Overall layout of the outside areas and Longitudinal Profile, Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Revista Arquitectos, no.155-156, Lisboa, 1996).

Figure 21 – Plan of the first floor and Section A, Residence of the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio. 1995-1996 (Source: Revista Arquitectos, no.155-156, Lisboa, 1996).

4. Influences on Bak Gordon’s architecture

In order to discuss the influences on Ricardo Bak Gordon’s architecture, we need to go back to the beginning and trace the panorama of his architectural training, while also situating him within the national and international architecture panorama of the time. The Portuguese architecture scene in 1990 was divided between Lisbon and Porto, two very different gravitational poles, much more so at that time than today. These are the only public schools of architecture in the country, together with a third private school, the Cooperativa Árvore in Porto. Escola do Porto reflected the signature style of the architect Álvaro Siza, but also that of Fernando Távora, Nuno Portas, and other architects who were actively involved in the 25 April transition to democracy, in both politics and architecture. Because of this, the School was promoted at the international academic level, and gained recognition from theorists like Kenneth Frampton, who coined the term “critical regionalism”. At the opposite pole, the Lisbon School was guided by post-modernism, with figures such as the architects Tomás Taveira, Manoel Vicente, José Deodoro Troufa Real, among others. These Lisbon architects were focusing on renowned names on the international architecture scene, especially North American and Anglo-Saxon ones, such as Peter Eisenman, James Stirling and Michael Graves. However, there were architects in Lisbon who did not follow post-modernist precepts. João Luís Carrilho da Graça and Gonçalo Byrne, together with the Porto School, coined the image of Portuguese architecture as white architecture, disregarding the post-modernist tendency. In 1989, the Academie Française organized an exhibition of European architecture in Rome, called “Lieux d’Architecture Européenne”, curated by Jean-Pierre Pranlas-Descours, with examples from Madrid, Paris and Lisbon. The catalogue text, written by Kenneth Frampton, praises modern architecture and the studios which act as centres of resistance in the face of the downgrading of architecture and theoretical debate. This exhibition was an important milestone in the European scene of the 1990s, disseminating the most prominent names in architecture from Spain, France, Italy and Portugal.

Born in Lisbon in 1967, Bak Gordon did not have any early contact with architecture in his family and close circle. In 1985, he began studying architecture at the Faculty of Porto and graduated 5 years later. During this time, he studied abroad in Milan as part of the Erasmus scheme. It is in this context that the architect was located between two cities represented by two schools with very different approaches, and a third that was even more different – the Politecnico di Milano, which contributed strong references to Italian modernism, such as Aldo Rossi and Giorgio Grassi. Being exposed to these very different ways of seeing architecture gave Ricardo Bak Gordon great freedom to navigate the waters of a multifaceted architectural vision. During his professional activities while at college, he passed through architecture offices without identifying himself or evolving under a tutelary shadow, as did other architects of his generation. In 1990, after graduating, he opened the Vilela & Gordon studio together with his partner Carlos Vilela Lúcio. This joint trajectory ended in 2000, when he founded the Bak Gordon Arquitectos studio, where he has been working for 24 years. This freedom, which emerged in the context of training in different colleges and cities can only happen naturally, fuelled by curiosity. The curiosity factor is a two-way street, an exchange. In the architect’s words, “it’s not just what you get, it’s also what you’ve already prepared to give.” (Interview with Bak Gordon, 2024). It is about the freedom to make space within yourself to receive knowledge.

In the context of the trajectory between different countries and cultures, there is the event, the condition that unequivocally changes the course of Ricardo Bak Gordon’s professional and personal life. Winning his first contest, 8 thousand kilometres away, in a continent and country so far away, but at the same time so connected to Portugal, was the seed that has sprouted ever since, opening up space in this fertile territory of the third bank. After winning the contest, Bak Gordon decided to travel to Brazil to satisfy his curiosity and enchantment with this country about which so much was known, but was thus far unknown to him. For him, the leading figure of Brazilian architecture was the architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha, whose work he knew through a monograph published by Gustavo Gili in 1996. He decided to contact Paulo when he visited Brazil and the two met in São Paulo, marking the beginning of a lasting friendship that continues to this day, even beyond the physical world.

Figure 22 – Paulo Mendes da Rocha and Ricardo Bak Gordon (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

He visited modern Brazilian architectural masterpieces and studied them closely. Public buildings such as MuBE, MASP or FAU-USP made an impact and served as inspiration, contributing deeply to his understanding of architecture. Freedom, a characteristic that was present from an early age in the architect’s career, found in Brazil the catalyst for change in his form of expression, on a completely new scale. In the words of Ricardo Bak Gordon, the visit to Brazil was the seed that generated

“a relationship of curiosity and discovery; discovery of the place, discovery of architecture, discovery of the people and also discovery of how much of Brazil, after all, could be said it was already inside me. And that is maybe what “the third bank of the river” means, if you allow yourself to be conquered, it’s because part of this seed is already within you.” (Interview with BAK GORDON, 2024)

One of the first large buildings in São Paulo, MASP was conceived in 1957 and inaugurated in 1968 by Lina Bo Bardi, a Brazilian architect of Italian origin. Built entirely in reinforced concrete and glass, the parallelepiped volume seems to defy the laws of gravity by fixing, through an immense free span, a piece of landscape on Avenida Paulista. The free span of MASP, a literal and metaphorical expression of one of the precepts of modernism, became a meeting point for artistic and political demonstrations in the city.

Figure 23 – MASP, Lina Bo Bardi, 1957-1968. Photograph by Luiz Hossaka, Archive of the Centro de Pesquisa do MASP (Source: https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/905090/masp-de-lina-bo-bardi-completa-50-anos?ad_medium=gallery).

FAU-USP, a project by Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi, was built in 1961. Considered a paradigm of São Paulo architecture, it was, from the beginning, more than a building: a political manifesto resulting from a reform of the educational system of architecture and urbanism, constructed in reinforced concrete. Vilanova Artigas provides key lessons about free and democratic spaces through a building at the service of society, elevated on common ground, which housed “a new university lifestyle (…) a space that favoured education of the human element.” (BAROSSI, 2016: 90)

Figure 24 – FAU-USP, Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi, 1961. Photograph by Raul Garcez Pereira, Vilanova Artigas Collection donated to the FAU-USP Library (Source: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/building-brazil-from-the-cariocas-to-the-paulistas-to-the-now).

Echoing all these values of Brazilian architecture, Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s work is characterised by a great capacity for synthesising a poetic vision, where “the distinction between sketch and concept becomes practically non-existent” (SCHENK, 2010: p.18). The concrete volume of MuBE, hovering over the infinite floor of the city, materializes in a shadow that creates architectural emotion. The building itself becomes a welcoming sculpture, with the canopy subtly raised in the landscape, like a “stone in the sky”. (PERRONE, 2011)

Figure 25 – MuBE, Paulo Mendes da Rocha, 1995. Photograph by Manuel Sá (Source: https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/924963/museu-brasileiro-da-escultura-e-ecologia-pelas-lentes-de-manuel-sa).

Figure 26 – MuBE presentation sketch, Paulo Mendes da Rocha. (Source: Revista Projeto, no.183, 1995).

5. Revision and extension of the competition

In 2003, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs requested a second version of the project, this time with reduced dimensions to reduce costs. After all, the previous one had been an approximately 160 by 40 metre building, rising 21 metres above Praça de Portugal, a volume very similar to the Museu dos Coches, built many years later in Lisbon, designed by Paulo Mendes da Rocha. A large metal box housing, in addition to what was required by the program, a piece of the Amazon rainforest. An ambitious project that, due to its scale and degree of complexity, overran the construction budget at that time. But, given the historical background of the Embassies of Portugal, it is likely that there are multiple reasons behind the decision not to go ahead with such an important building, and that this had much more to do with political will.

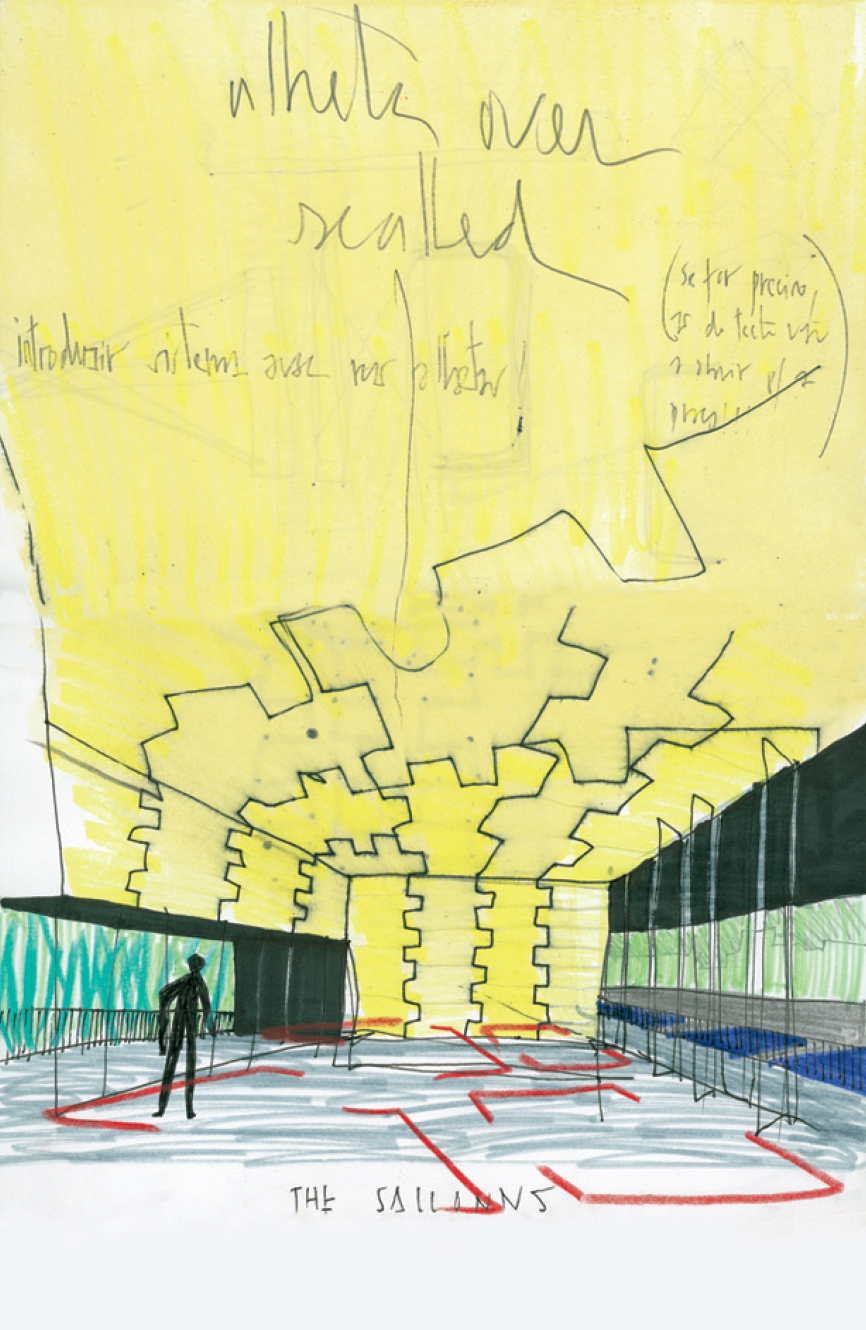

Ricardo Bak Gordon and Carlos Vilela Lúcio now had separate professional trajectories, but they teamed up again to respond to this new request. The result was Project 2, headed by Bak Gordon Arquitectos. This time the challenge was to find a solution that was easier to build, without losing sight of the initial concepts, which remained in the second version, but were now configured differently, in a volume made entirely of reinforced concrete, much more in line with the architectural landscape of Brasília. Aiming to offset the institutionalism of the Portuguese diplomatic mission and the design of a comfortable, intimate family residence, the project once again addressed the issue of climate:

“how to deal with a place that has always been a paradigm of the modern world, a planned, artificial city, but with an austere and dry climate that indispensably lacks a response.” (BAK GORDON, 2020: 141)

Figure 27 – Conceptual sketches for the second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 28 – Conceptual sketches for the second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 29 – Conceptual sketches for the second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 30 – Conceptual sketches for the second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 31 – Conceptual sketches for the second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

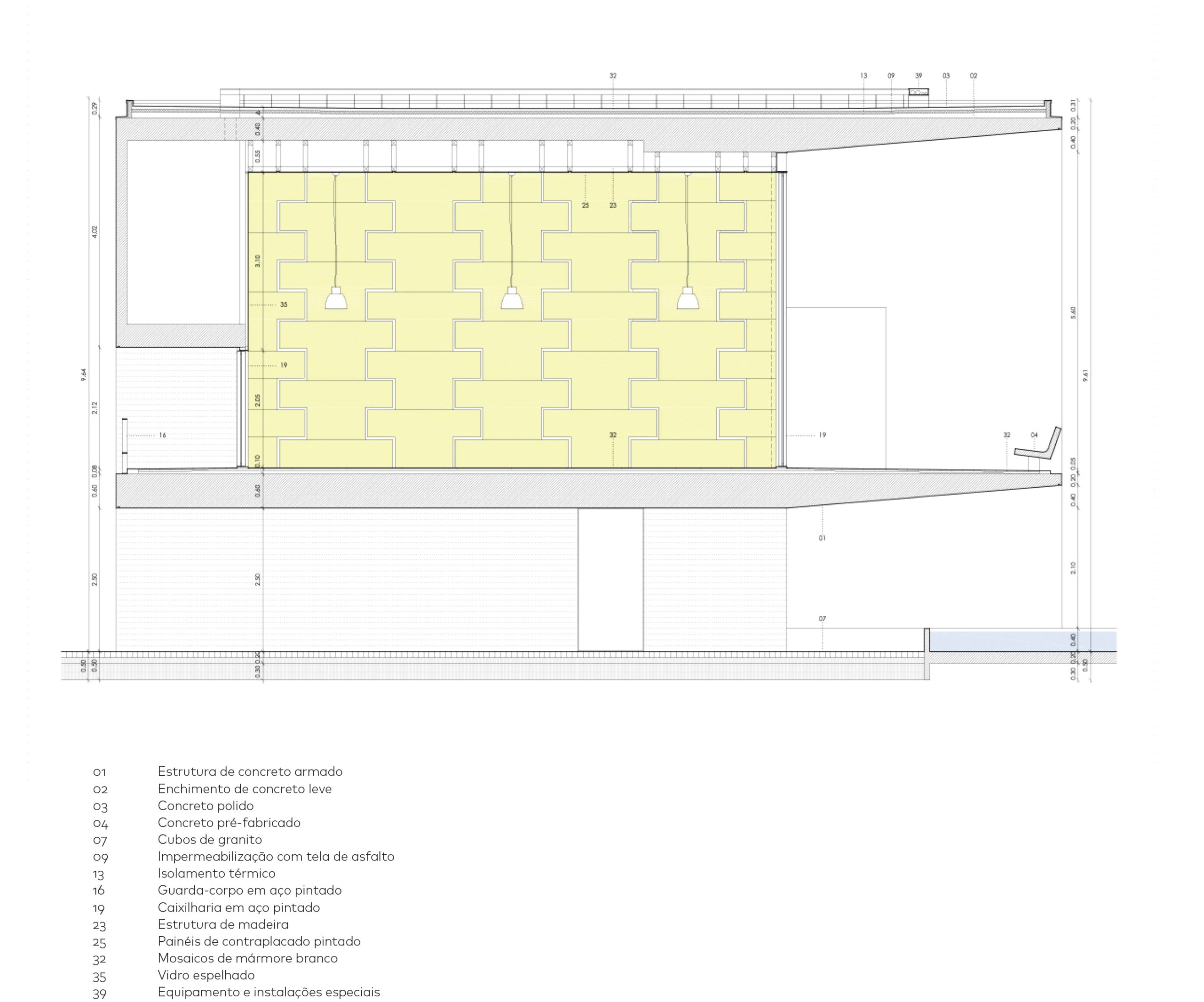

The answer was found, once again, in the determination to geometrize the built landscape. The building is implemented in a Cartesian construction that seems to levitate over an infinite floor, a direct influence from modern Brazilian architecture. The built mass, of alternating full and empty spaces, was separated at its four limits, through two main juxtaposed volumes, one housing the family residence and the other, auxiliary spaces for the diplomatic representation, and two laminar volumes, raised from the floor, intended for access and circulation. In the middle, a green mass takes root through the cloister courtyard feature, a kind of hortus conclusus that, in addition to providing the necessary privacy for the program, counters the climate issue:

“an artificial landscape, intensively planted and humidified by a series of mirrors and water tanks, ensures a micro climate capable of providing the necessary comfort throughout the year.” (BAK GORDON, 2020: 141)

Figure 32 – Location plan, Bak Gordon Arquitectos (Source: Revista América: revista da pós-graduação da Escola da Cidade, no. 2, 2020: p. 142).

Figure 33 – Conceptual sketch for the second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 34 – First and second floor plans, second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 35 – First and second floor plans, second version of the project. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

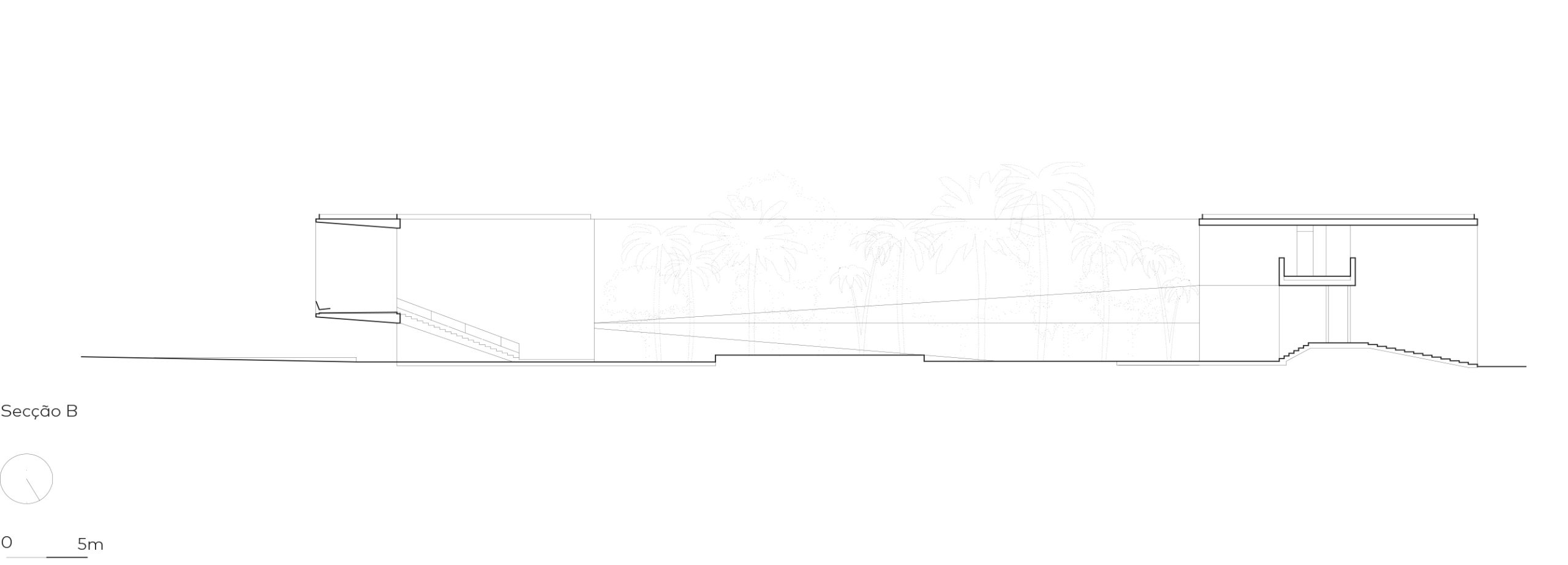

The permeability of the built bodies, at times visual, at times physical, integrates the building into this new landscape, now exposed to the open sky, while also creating a closer relationship with the existing Chancellery building. With regard to Chorão Ramalho’s unbuilt Residence, in this second proposal we see a closer reference to the position, the scale, the distance. The building no longer aspires to palatial dimensions and has a more domestic, more airy form, without confronting the Chancellery. Whereas the first project was a radical proposal, the second manages to identify more with its surroundings, and uses more durable materials, thus avoiding the need for long-term maintenance. As Bak Gordon explains in the interview, the second solution did not offer significant savings from the perspective of investment. However, this was not the reason for not building it, but rather a dystopia between the political consciousness and that of the representation and construction of public places.

Figure 36 – Conceptual sketches. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 37 – Conceptual sketches. 2003 (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 38 – Photo of magnified scale model ( Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

Figure 39 – Building cross section, Bak Gordon Arquitectos (Source: Revista América. Revista da pós-graduação da Escola da Cidade, no. 2, 2020: 149)

Figure 40 – Sections A and B, Bak Gordon Arquitectos (Source: Revista América. Revista da pós-graduação da Escola da Cidade, no. 2, 2020: 144-145).

Figure 41 – Sections A and B, Bak Gordon Arquitectos (Source: Revista América. Revista da pós-graduação da Escola da Cidade, no. 2, 2020: 144-145).

Figure 42 – Collage by the author made from photos of the model (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

6. Continuity: the third bank of the river

What is, after all, the third bank of the river? Even though, in an immensely versatile manner, Guimarães Rosa’s short story offers a very rich basis for meanings and interpretations that have been widely analysed and categorized by literary critics, it is open ended, without no apparent outcome. Rosa’s narrative shows that what is left are doubts, rather than the certainty of possible solutions. Bárbara Del-Rio Araújo’s thesis explores a new interpretation of the short story, based on definitions of modernity and modernism, which contradicts the frequent transcendental or mystical readings. According to Bárbara Del-Rio Araújo, what the narrative of Guimarães Rosa

“follows is the logic of a world that resists classification and it ends with the impossibility of choosing between one thing and another, of arriving at a clear-cut, unique and final answer. Everything there is twofold, antagonistic, divisible and ambiguous; marked by the laceration of the world and modern man.” (ARAÚJO, 2016: 19)

Literature and architecture meet in this common current, the culture of the modern world, with all its complexities and contradictions. On the one hand, we can understand the third bank as this place suspended between two countries, with different histories and cultures that are intertwined. The two versions of the Residence project for the Embassy of Portugal in Brasilia, by Bak Gordon and Vilela Lúcio, attempt to disclose the in vitro representation of a country’s culture within another country. In the process, a new place is created at the confluence of Portugal and Brazil: a shelter for people, whether they are citizens of one country or another, or from one inside another.

On the other hand, we can conceive of the third bank as an internal space, suspended between the two banks, in constant movement. In nature, we know that rivers carry large amounts of suspended sediment, and that the load depends on the speed of the current and diameter of the particles. This is a cause-and-effect ratio: the heavier the weight, the more intense the current. In the same way, those of us who travel the world collect places, experiences and memories in this inner space, an extremely subjective and extremely sensitive one. In the opening section of his third monograph, Ricardo Bak Gordon refers to “our condition of being midway between all the places we have been, and those we have yet to visit” (BAK GORDON, 2021), like an inner gold mine where we gather all the virtues of the places which make an impact on us, a mine of personal restlessness that is constantly in motion. For Bak Gordon, “the condition of our life relates to places, it relates to time, it relates to multiple circumstances” (Interview with BAK GORDON, 2024), and the richest part of this condition is its unpredictability. When freedom – born from curiosity – lies front of us, we should allow ourselves to be exposed to it. It is within this third bank that the architect says his practice is situated. (BAK GORDON, 2023)

For Paulo Mendes da Rocha, the aim of architecture is to shelter life’s unpredictability. His poetic, universal vision reflects a huge capacity for synthesis, which was increasingly honed throughout the architect’s life. In a 2018 interview with El País, he says:

“Deep down, architecture is us, and a city is made up of the behaviour of people rather than buildings. Architecture shelters this unpredictability of life.” (TEIXEIRA, 2018).

Figure 43 – Paulo Mendes da Rocha and Ricardo Bak Gordon. (Source: Collection © Bak Gordon Arquitectos).

The competition was how Ricardo Bak Gordon and Paulo Mendes da Rocha met and began their professional relationship, which became a personal one. But while it is true that the life‘s unpredictability brought the two together, it is also true that something of Mendes da Rocha’s way of looking at the world already existed within Bak Gordon. Passing through also means allowing oneself to be passed through. This study, as well as the tale of the “Third Bank of the River”, does not attempt to end with conclusions, but rather to open up the conversation, so that others may continue it. One of Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s most inspirational statements, paraphrasing Hannah Arendt, states that “we all know that we are going to die, but we know that we were not born to die, we were born to continue” (TEIXEIRA, 2018). He believed that the essence of human existence is to pass on what we know to others. A little, or a great deal, of him remains today, after his death, in the various people who continue his work, guided by Paulo’s unique curiosity and optimism.

At the end of the interview with Ricardo Bak Gordon, when asked about what he thinks has remained and will remain, like the DNA that has permeated his work ever since that initial moment in the 1990s, the architect confessed that he has not given it a great deal of thought. He refers to a degree of humility and dedication to the work, believing that architecture is more to be lived in than displayed; living intensely and taking care of the work in all its phases. He also speaks of a certain kindness, a means of adding value to the experience of architecture:

“If you come home and put the key in the door and you have a little light that illuminates your key and your hand, it’s nicer than if you don’t. Firstly, because you can see the lock. Secondly, because there is a symbol that welcomes you when you arrive. It may be a simple light, but at the same time it represents a certain kindness.” (Interview with BAK GORDON, 2024)

Another characteristic, also typical of Paulo Mendes da Rocha, is the freedom created by a sense of distance, of starting each project as a blank sheet: the freedom to start afresh, one freedom at a time. Even if the architect confessed to rely on the fact that he has little memory of things, the act of forgetting is nothing more than the access key to the inner gold mine that allows to resurrect, under his own lens, the values stored there.

Figure 44 – Photograph of the Bak Gordon Arquitectos studio, taken during the research interview. 2024 (Source: Photograph by the author).

Bibliography

2G Bak Gordon. no. 64. Spanish-English bilingual edition. Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2012.

ARAÚJO, Bárbara Del-Rio – A Poética Moderna em ‘A Terceira Margem do Rio’, de João Guimarães Rosa. In Tese, vol. 22, no.1. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2016.

Arquitectura n.º 130. Lisbon: Publicações Nova Idade, 1974.

Architécti n.º 35. Lisbon: Editora Trifório, 1997.

BAK GORDON, Ricardo – 17º seminário internacional: Tanto mar. Ocupar, transformar e morar. Uma contribuição da arquitetura portuguesa para novas formas de viver na metrópole. [Video recording]. Produced by Escola da Cidade. São Paulo: 2023. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=du4GbN3GSGw&t=3338s

BAK GORDON, Ricardo – Residência para a Embaixada de Portugal em Brasília. América: revista da pós-graduação da Escola da Cidade. São Paulo: Editora Escola da Cidade, 2020, no. 2.

BAK GORDON, Ricardo – Bak Gordon. Architecture. Lisbon: A+A Books, 2021, Bilingual Portuguese-English edition.

BAK GORDON, Ricardo – Bak Gordon. Architecture. Lisbon: Guimarães Editores, 2009.

BAK GORDON, Ricardo – Bak Gordon. Architecture. Lisbon: Librus, 2005.

BAROSSI, Antonio Carlos – O edifício da FAU-USP de Vilanova Artigas. São Paulo: Editora da Cidade, 2016.

BAPTISTA, Luís Santiago – Arquitectura em concurso: Percurso crítico pela modernidade portuguesa. Porto: Dafne Editora, 2016.

Brasília no. 3. Rio de Janeiro: Compania Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil, 1953.

CARNEIRO, Luís – Três Embaixadas Portuguesas: Londres, Madrid and Rio de Janeiro – Arquitectos Irmãos Rebelo de Andrade. Porto: Edições Afrontamento, 2021.

CARVALHO, Ricardo – Portugal in vitro. J-A Jornal Arquitectos. Lisbon: Ordem dos Arquitectos, 2003, no. 212, p. 58-63.

Catálogo 3a Trienal de Arquitectura. Sintra: Museu de Arte Moderna, 1998.

FERNANDES, Manuel Correia – Catálogo Concurso Público para a Elaboração do Projecto da Residência da Embaixada de Portugal em Brasília: Exposição dos trabalhos concorrentes. Olival Basto: Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros, 1955.

Jornal Arquitectos no. 155-156. Lisbon: Associação dos Arquitectos Portugueses, 1996.

PERRONE, Rafael Antonio Cunha – Passos à frente: algumas observações sobre o MUBE. Arquitextos. Ano 12, no. 136.03. São Paulo: Vitruvius, 2011. Available at: https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/12.136/4042See [Consulted 28/06/2024].

RIBEIRO, Rogério – Exposição Raul Chorão Ramalho, Arquitecto. Lisbon: Livraria Castro e Silva, 1977.

ROSA, Guimarães – A Terceira Margem do Rio. In Literatura Comentada. São Paulo – SP: Editora Nova Cultural Ltda., 1990, p. 105-110.

SCHENK, Leandro Rodolfo – Os croquis na concepção arquitetônica. São Paulo: Annablume, 2010.

SLONEANU, Delia – Entrevista a Ricardo Bak Gordon. [Audio recording]. Lisbon: 21 June 2024. Personal communication.

TEIXEIRA, Ruy – Mendes da Rocha: “A cidade é feita mais de homens do que de construções. [Online]. São Paulo: El País, 2018. Available at: https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2018/10/08/cultura/1539001730_157977.html [Consulted 28/06/2024].