Andrea Salazar Veloz

afsalazarv@uce.edu.ec

Urban architect. Professor, Central University of Ecuador, Equador. Doutoranda no Departamento de Arquitectura da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (Da/UAL). Researcher at CEACT/UAL, Portugal

Alejandro Becerra Martínez

marcelo.becerra@unach.edu.ec

Urban Architect. Professor, National University of Chimborazo, Equador

For citation: SALAZAR VELOZ, Andrea; BECERRA MARTÍNEZ, Alejandro – Quito’s Regulatory Plan. 1942-1945, by Guillermo Jones Odriozola. Estudo Prévio 23. Lisbon: CEACT/UAL-Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2023, p. 106-116. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available on: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/23.01

Review received on 17 July 2023 and accepted for publication on 13 September 2023.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Quito’s Regulatory Plan, 1942-1945, by Guillermo Jones Odriozola.

The Regulatory Plan of Quito drawn up between 1942 and 1945, drawn up by the Uruguayan architect Guillermo Jones Odriozola (1913-1994), was a fundamental document and starting point for the history of Ecuadorian urbanism. This plan sought to regulate the growth of the city of Quito through a proposal for a more efficient and equitable spatial organization emphasizing three fundamental axes: housing, work and leisure.

It is important to understand the historical context in which this plan was developed in order to realize its scope and relevance. In the years prior to its elaboration, Quito experienced an accelerated urban growth driven mainly by the arrival of migrants and the construction of new neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city. This disorderly expansion generated serious problems of traffic congestion, lack of basic services and housing insecurity. Faced with this situation, the Quito city council decided to convene a group of experts to develop a regulatory plan to order the city’s urban growth. Jones Odriozola, who had participated in the development of regulatory plans in Uruguay[1], was one of the architects selected to lead this project.

In his first impression of the city of Quito, Odriozola stressed that it was “a pure city” (ODRIOZOLA, 1945: 7), which had not been affected by the phenomena of modern life that have altered most cities in the world. According to the urban planner, this condition caused the city to be marked by a slow evolution that did not allow it to develop the minimum elements necessary to express its condition as a capital. Therefore, Quito’s 1945 regulatory plan represented the opportunity to put forward a proposal for a visionary urban planning on a large scale.

Context

Jones Odriozola would begin the development of the urban plan for the city of Quito with a conceptual reference on the importance of understanding the legacy of ancient cities in order to understand the cycles that they had gone through from their formation to their extinction. Consequently, Odriozola would delve into the analysis of the historical and contemporary urban context of the city of Quito in order to interpret the processes that shaped the city so he could channel them into a comprehensive proposal adapted to the national reality. In this regard, the plan established:

“The duty of the urban planner, when formulating a Regulatory Plan, should not only be to take into account the entire future of the city but, relying on a whole past consisting of urban “facts”, to formulate a harmony with the development of the future” (ODRIOZOLA: 1945: 12).

By the time the plan was carried out, Quito had already accumulated four centuries of history since its Spanish founding in 1534. The urban form that characterized the historic center of the city until the end of the 19th century was essentially defined by the Laws of the Indies, which established an organization of regular streets and blocks. This form of urban organization did not contemplate an overall vision that would direct the growth of the city. From its conception, the choice of a concentric shape, alien to the rugged characteristics of the geography and the lack of consideration for the Inca road systems prior to its foundation, limited the growth of the city. As a result, the latter was unable to exceed the limits established in the initial plan, condemning its development inland. Subsequently, the urban population, contained in a slum historic center, exceeded the originally established limits, and under the need for new spaces to inhabit, the city began to expand with as its only reference a central axis that would be extended — to the south, beyond El Panecillo, and to the north, from La Alameda, defining a new longitudinal form of territorial organization.

In its purpose of understanding the urban “facts” contemporary to the time in which the plan was carried out, Odriozola’s study made an initial assessment of the qualities and weaknesses of Quito. This analysis, which would be based on historical documentation that essentially included demographic and morphological data, revealed the evolutionary process of the city, as well as allowing the identification of the main problems and challenges to which the plan had to respond.

Regarding the demographic aspect, it was identified that in the years prior to 1942 – when the plan began – population changes were not adequately managed, causing an imbalance in the urban fabric of the city with densely populated areas in the center and north of the city, compared to others with low occupancy rates. Faced with such a situation, Odriozola’s team carried out a projection of inhabitants until the year 2000, predicting a population of approximately 700.000,00 people, this being the population base with which the plan was worked.

Likewise, aiming to have a clear understanding of the morphological evolution and patterns of urban growth, the team in charge of the urban plan would carry out the comparative study of four historical plans of the city:

“The first was that of Alcedo y Herrera, which dates from the end of the 17th century (Figure 1); then, the plan of the Geodesic mission corresponding to the year 1740 by an unknown author (Figure 2); the following is the plan made by J. Gualberto Pérez dated 1888 (Figure 3); and; finally, the plan published by order of the Intendant General of Quito, Mr. Antonio Gil and corresponding to the year 1914″ (ODRIOZOLA: 1945: 18-19). (Figure 4).

Figure 1 – Plan of Alcedo y Herrera, 1734 (Source: FONSAL Archive).

Figure 2 – Plan of the Geodesic mission, 1740 (Source: National Library of France. Available: https://gallica.bnf.fr).

Figure 3 – Plan by J. Gualberto Pérez, 1888 (Source: National Library of France. Available: https://gallica.bnf.fr).

Figure 4 – Plan by Antonio Gil, 1914 (Source: National Library of France. Available: https://gallica.bnf.fr).

The critical and systematic study of these documents, carried out by Odriozola and his team, would result in the following general observations which, for the purposes of this review, were classified in thematic areas:

Architecture and landscape:

- San Francisco de Quito possessed (and still possesses) the most interesting set of architectural values in all of Latin America.

- Both the landscape and the urban fabric of the city were strongly influenced by the presence of three natural elements: the slopes of Pichincha, El Panecillo and Itchimbia; also, the ravines that cross the city.

- It also highlights the architectural value of the historic centre, proposing its protection against the intrusion of new elements that differ from the existing one, through projects that integrate harmoniously into its urban image.

Growth urban and zoning:

- Due to its intricate topography, the city of Quito developed a growth pattern that extends predominantly in a north-south direction.

- Until 1924, there was a balanced ratio of “free mass to built mass” in the urban fabric.

- There was no clear, appropriate and defined zoning, much less with regard to government centers or buildings of public utility.

- A functional mix of completely different elements was witnessed in the different areas of the city.

- Private space was prioritized over public space.

Mobility and transport:

- There was no real and deep relationship between the city centre and the banking centres, business centres, department stores, etc.

- Tendency of the city to shift its business center to the north.

- Mobility problems, congestion and vehicle accumulation both in the historic center and in the surrounding areas.

- Hegemony of the vehicle over the person.

- There was a need for the implementation of an efficient and equitable urban transport system throughout the city.

- Extra-urban transport, such as trains and buses, was disconnected from urban transport, evidencing a disharmony throughout the system.

- It was necessary to articulate the city centre with the rest of the country, with a mobility system that did not cross the historic centre given the impossibility of widening its streets.

- The airport’s location and connectivity with the city centre was highlighted, as well as its importance as a connection point with the rest of the countries in the region.

Green spaces and quality of life:

- Lack of quality green spaces such as parks, gardens or promenades with a wide spatial sense that contribute to recreation.

- There were some well-located markets; however, these did not meet the hygienic conditions for the supply of groceries.

- Scarcity of spaces dedicated to culture.

This would be the context when the preliminary project of the urban planner Jones Odriozola began to be prepared. The previously detailed observations made it possible to propose specific operational strategies on which the Regulatory Plan of Quito would be based in its objective of proposing a plan adjusted both to the reality of the city – at the time – and for its future.

Description

Faced with evident disorganized urban growth, the Quito City Council recognized the need to plan the city seeking to improve the way of life of the inhabitants and to adapt it to the new modern socio-economic conditions. The development of Quito’s Regulatory Plan would take as a paradigm the postulates of modern urban planning, thought adapted to the context. The Regulatory Plan, thus, presented an innovative approach to city planning by considering it as an indivisible totality that required a holistic vision that was desirable and materializable in the future.

The plan would also incorporate, for the first time in Quito’s urban planning, citizen participation and criticism as a fundamental axis for its implementation. Odriozola considered as a basic guideline, “for all human action tending to formalize or regulate the seat of the human conglomerate, at the will of the people” (ODRIOZOLA, 1945: 10).

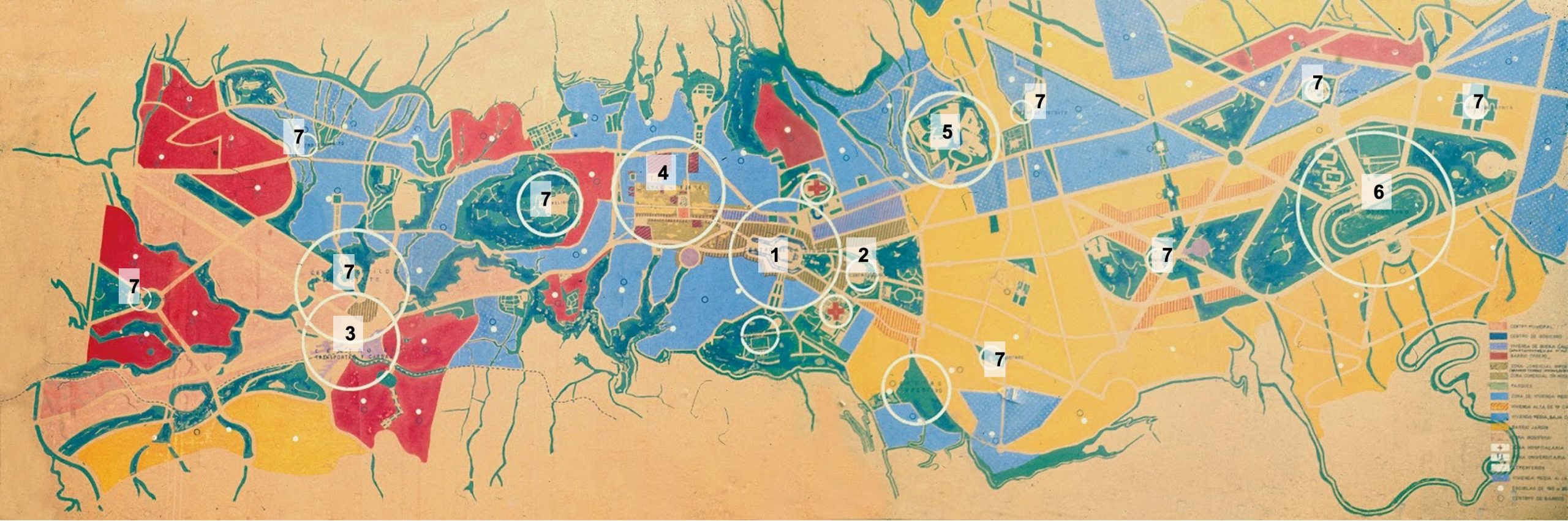

The first links in the plan would be formed by the creation of the so-called Civic Centers (Figure 6). Its location and conception regarded both the physical facts of the city and the spiritual ones – legends and traditions. It did consider:

· The Civic Government Center, which would be in the center of the city, close to the Monument of the Liberator, its location was privileged for the landscape, symbolic and accessibility possibilities. The Center of Government would comprise the headquarters and offices of the three branches of the Ecuadorian state: executive, legislative, and judicial (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Model of the Civic Center of the Regulatory Plan of Quito, 1945 (Source: Monard, 2019: 70-71).

· The Cultural Center was located in front of the Civic Center of Government, a location that would allow it to be configured as an obligatory step that would make art relevant. It was designed as a building that would concentrate functions of teaching and artistic dissemination.

· A centre for the transport of passengers and correspondence, planned in the current sector of La Marín, it was “conceived so it would establish a perfect link between the extra-urban transport that reaches the city and the collective transport systems” (ODRIOZOLA, 1945: 27).

· Municipal Center, it was implanted towards the Plaza de la Independencia due to the architectural quality of the buildings that existed there, which kept the tradition and quality of other times.

· As a University Center, the ideas that would govern this center were those of spatial spaciousness and architectural composition of high plastic quality that would make up a harmonious and efficient whole. The proposed location considered the easy access from the different points of Quito.

· Sports Center, would consist of a system of parks and park-avenues located mainly to the north of the city. Four premises were considered: “functionalism, plasticism, use of the natural conditions of the land and use of the large municipal lands of that area” (ODRIOZOLA, 1945: 30). Likewise, the buildings that would be part of this center should give rise to aesthetic emotions and highlight the landscape.

· Neighbourhood civic centres, the plan contemplated the implementation of several of these centres, whose main objective was to bring together all those services necessary to ensure minimum conditions of urban habitability in the different areas of the city. These centres would consist of: shops, cinemas, sports areas, post offices, bank offices, schools, markets and transport centres.

Figure 6 – Plan of the 1945 Regulatory Plan with its civic centres. 1. Civic Government Center 2. Cultural Center 3. Passenger Transport Hub 4. Municipal centre 5. University Center 6. Sports centre 7. Neighbourhood civic centres (Source: Metropolitan Directorate of Territorial Planning).

Another of the fundamental aspects to which Odriozola paid special attention, in the design of the plan for the city of Quito, would be the implementation of quality urban green spaces, in correspondence both to the urban surface area and to the number of inhabitants projected until the year 2000. To emphasize the importance of incorporating urban greenery, Odriozola transcribed in the plan a few paragraphs from the work of the Chinese philosopher Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living, where the value of open spaces for inhabitants is emphasized. Therefore, the approach for its execution consisted of “devising a total system that would allow us to travel throughout the city by means of “greens” that would be linked to each other and thus provide the ease and beauty of walking among plants and flowers, through the various points of interest of the city” (ODRIOZOLA, 1945: 34). The historical and topographical condition of Quito for its location was evaluated, determining that the best places to arrange the three main urban parks of Quito were in El Panecillo, Itchimbía and the eastern slopes of Pichincha.

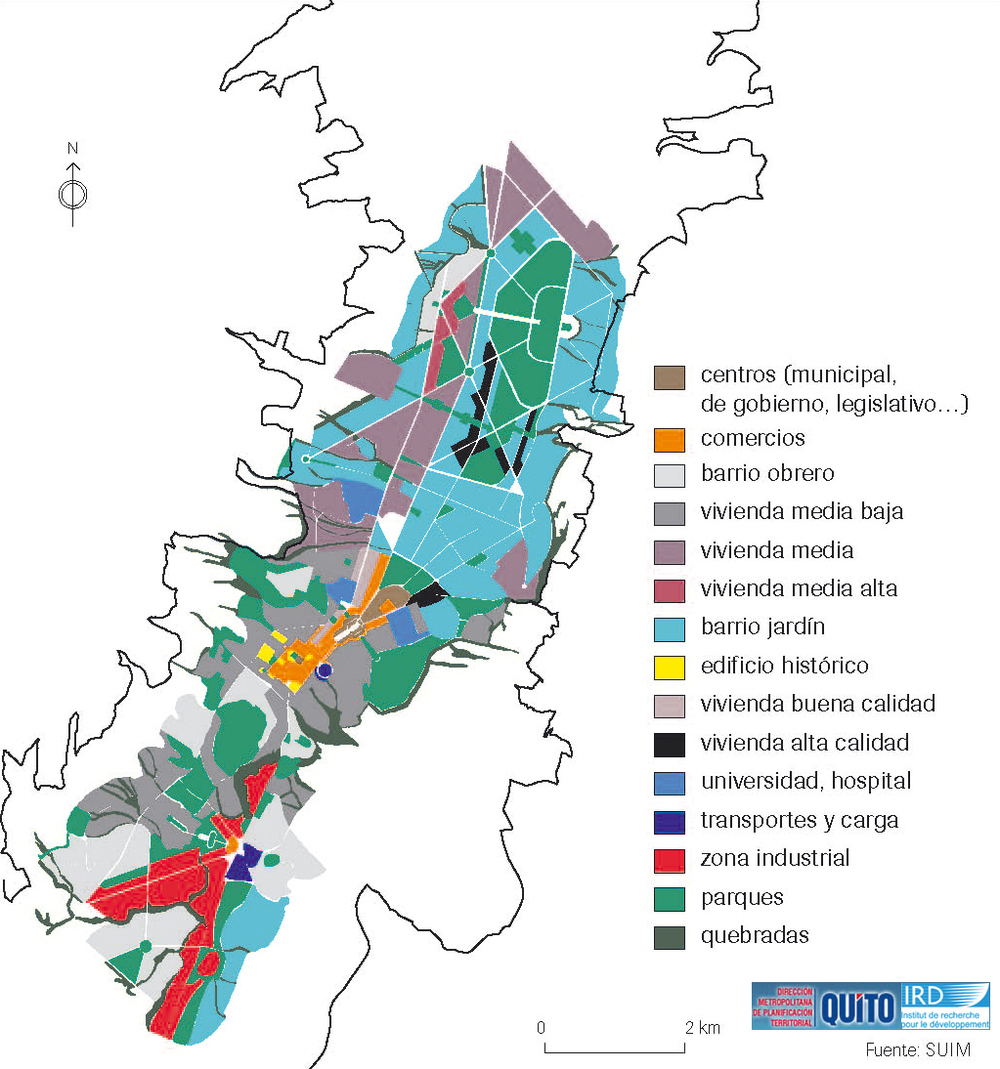

In addition to the civic centers and green areas established by Odriozola for the city of Quito, his plan contemplated the functional division of the city based on three fundamental activities: work, recreation, and housing, in correspondence with the spatial and social configuration of the city (Figure 7):

· In the city centre, the municipal centre would be established; government center; department stores, shops, offices and banks; Low quality housing and hospital area.

· To the north would be the high-rise, first-class housing for employees with a garden; medium-quality housing – two-storey building; medium-quality housing with garden; Neighbourhood-garden and university area.

· In the south of the city there would be medium-low quality housing of good quality with a garden; good quality low house with garden and businesses; industrial zone and working-class neighborhoods.

Figure 7 – Zoning according to the 1945 Regulatory Plan (Source: Metropolitan Directorate of Territorial Planning).

Likewise, the Quito Regulatory Plan would present a road proposal for the articulation of the different areas of the city through a road network categorized by types of arteries.

Finally, Odriozola prepared a technical and economic feasibility proposal that would allow the implementation of the plan in phases, here the minimum initial works that had to be established to materialize it were detailed.

Evaluation

When presenting the proposal for Quito’s regulatory plan, the groups of former city councilors, the Civil Engineers guild and the Municipal Public Works Commission met for its analysis, approval and execution. Among the various reports submitted by these technical and administrative groups, the importance of the proposal and, above all, the need to implement it was highlighted. Reading the different evaluations made by experts, the suggestion of implementing a real industrial center in the south of the city while respecting the already existing clusters is striking. In addition, it was emphasized that the projection for the development of the south of the city should maintain a balance analogous to the expansive growth of the north and recommended the development of a more detailed study of the connection and mobility between the south and the north on the western and eastern slopes in order to have a pragmatic solution.

Another aspect to highlight in the evaluation phase of the urban plan lied in the fact that the city council decided to hire international experts with academic and urban planning experience to carry out a broad and detailed analysis. Among the professionals summoned are the Peruvian architect Emilio Harth-Terré and the North American urban architect Chloethiel Woodard Smith. The favorable observations issued by both made it possible to give a greater theoretical foundation to Odriozola’s ideas, where references to the postulates of modern urbanism stand out above all.

Harth-Terré highlighted the adequate adaptation of the proposal to the natural and topographical configuration of the city, managing through the strategies implemented to highlight the existing natural values by incorporating them into the urban dynamics. In addition, in his report he supports Odriozola’s decision to spatially separate municipal and government powers, mentioning that this vision was in line with the new global thinking on the urban.

On the other hand, Chloethiel Woodard Smith warned that, in a plan of such complexity, the scarcity of health facilities went against the primary objective of a democratic city. He also referred to the fact that an efficient form of supply for the city had not been analyzed in detail, an essential condition considering the projection of population growth. Likewise, he agreed with the aforementioned reports on the need to generate a more effective solution for the connections between the south and north of the city. He also recommended the formation of technical organizations to carry out the plan, a political organization committed to the long term and working groups that promote the education of the inhabitants of the capital. For her, the sum of these principles would establish a fundamental program capable of adapting and complying with both the guidelines established by the plan and foreseeing possible modifications that must occur at the time of implementing it.

Transcendence

Although the Quito Regulatory Plan proposed by Odriozola was an ambitious and visionary proposal, it was only partially materialized. Above all, aspects related to the layout, roads, zoning and location of the city’s major facilities were contemplated. Due to its lack of pragmatism and disconnection with the socio-economic reality of the city and the country, focusing only on the prefiguration of the urban image of the city based on ideal-spatial models imported from abroad, in 1967 the project was replaced by the Urban Planning Master Plan.

Finally, several of Odriozola’s definitions and proposals have been taken as the basis for some subsequent plans; in this way, several of his principles continue to direct the operation of the current city, characterized by a radically marked socio-spatial inequality and segregation between the north and south.

Bibliography

MONARD, Shayarina — Arquitectura Moderna de Quito, 1954-1960. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña, 2019.

ODRIOZOLA, Jones — Plan Regulador de Quito. Quito: Imprenta Nacional, 1945.

Notes

1. Gilberto Jones Odriozola developed the Regulatory Plan for the city of Maldonado in 1939, and worked on the social housing construction project in Uruguay in the 1930s.