Victor Beiramar Diniz

vbd@netcabo.pt

Landscape Architect and PhD student at the Department of Architecture of the Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (DA/UAL), Portugal. CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, Portugal

To cite this article:

BEIRAMAR DINIZ, Victor – MORE SEA: Eduardo Anahory’s floating-beach-pool. Estudo Prévio 25. Lisbon: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, December 2024, p. 135-161. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/25.5

Received on July 31, 2024, and accepted for publication on October 11, 2024.Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

MORE SEA: Eduardo Anahory’s floating beach pool

Abstract

Eduardo Anahory (1917-1985), designer of architecture (BORGES, 2010), built a cosmopolitan career, unlike most architects of his generation, moving between Europe and South America, and gaining widespread international recognition for his work, which, nonetheless, is now largely absent from the history and criticism of architecture.

By investigating the design process of the floating-beach-pool, which he conceived in the late 1960s for the Tamariz beach, Estoril, and installed there during the summers of 1970, 71, and 72, this article seeks to rescue this singular achievement from its current relative obscurity. It also presents, as possible keys for analysis and interpretation, its inscription as an artefact within a landscape and the construction of its condition as an artefact-event.

Keywords: Eduardo Anahory, Seapool, floating beach pool, Estoril.

Figure 1 – The floating beach pool off the Tamariz beach, Estoril c.1972. (Source: Foretold, https://www.fotold.com).

1. INTRODUCTION

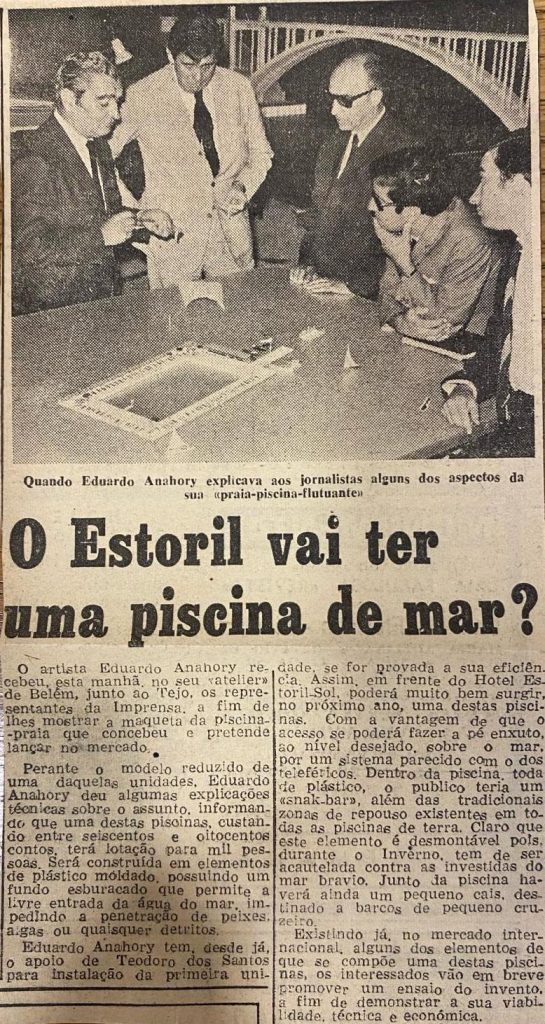

Figure 2 – Eduardo Anahory, at the presentation of the floating-beach-pool project, 1968 (Source: Diário de Noticias. Year 104 No. 36772, 20/07/1968, p. 7).

Eduardo Fortunato Jaime Anahory was born in 1917 into a Jewish family in Lisbon, and died in the same city in 1985, at the age of 67. He started early as a self-taught illustrator in publications of which his father was an editor, and later, in 1935, at the age of 18, began his formal education in fine arts in the Special Architecture Course at the Escola de Belas-Artes in Lisbon. Two years later, he transferred to the Escola de Belas-Artes in Porto, which he abandoned in 1938 in favour of learning through practice. His failure to obtain a degree prevented him from signing projects as an architect, a decision that would irrevocably mark his career.

His professional and artistic practices, inseparable from one another, created a spectrum of activity with no definable boundaries between his various expressions—sculpture, painting, graphic design, advertising, equipment design, furniture, set design, exhibition structures, interior architecture, and architecture — also characterized by Anahory’s state of constant movement and kind of wanderlust [1]: New York (1939) for the World’s Fair, Rio (1940-45) [2], Paris (1945-48), Lisbon (1948-52), back to Rio and São Paulo (1952-1954), and Lisbon again (1955-74) with frequent visits to Paris and a study visit to the Scandinavian countries (1963), and finally Angola and Brazil (1970-1984) [3].

Modern, more due to adapting their principles to the context than by adhering to doctrine (BORGES, 2010: 186), Anahory’s “architectural objects” reveal a formal sophistication, whether in an urban context or when isolated and confronted with the landscapes they inhabited, resulting from self-imposed restraint — “3 colours, 3 materials” (BORGES, 2010) — and a particular attention to construction detailing. This is evident especially, or even primarily, when employing prefabrication or ready-made construction and functional systems, whether technological or artisanal, which they explore and adapt. Cosmopolitan, unlike most of his contemporaries in Portugal, Anahory created unique spaces where a concern — almost hedonistic in nature — for comfort and the pleasure of their use is evident.

Such is the case — particularly unique, even within a body of work so full of singularities — of the design and realization of the floating-beach-pool, or Seapool. Its fleeting existence (during the summer months of 1970, 1971, and 1972) off the beach at Tamariz, in Estoril, promissing “more sun, more iodine, more sea — with all the comfort of a swimming pool” [4].

2. MORE SUN

2.1 The Anahory constellation

Anahory’s wanderlust, along with his extroverted and charismatic personality [5], enabled the creation of a true constellation of figures [6], around him, in a network that spanned geographies and blurred the boundaries between friendship and professional practice, significantly shaping his taste and informing his work.

The Lisbon milieu in which Anahory moved in the late 1930s, along with his role as an assistant in António Ferro’s team of decorative painters’ at the National Propaganda Secretariat during preparations for Portugal’s representation at the New York and San Francisco World’s Fair, placed him within the orbit of artists such as Carlos Botelho, Fred Kradolfer, Bernardo Marques, Emmerico Nunes, José Rocha, and Thomaz de Melo (Thom). Maria Helena Vieira da Silva and Árpád Szenes, passing through Lisbon at the end of the decade, also departed for Rio de Janeiro in 1940, just as Anahory did, the three reuniting in Paris in the early post-war years, and later again in Lisbon, cementing a friendship that lasted until the deaths of Árpád and Anahory in 1985.

During his time in Brazil, Anahory formed lasting connections with Jorge Amado, Vinícius de Morais, Dorival Caymmi, Lúcio Rangel, Rubem Braga, as well as with architects Óscar Niemeyer, Eduardo Reidy, Jorge Moreira, and the brothers Marcelo, Milton, and Maurício Roberto, with whom he collaborated. For the theatre director Louis Jouvet, exiled from the war in South America, he created sets for plays that would later be revived in Paris in the post-war years, where he also designed sets for the Portuguese ballet company Verde Gaio, further solidifying the recognition of his work in set and costume design.

A brief visit to Lisbon in the late 1940s added José-Augusto França to his list of relationships. Returning to Rio and São Paulo in 1952, at Niemeyer’s invitation, he crossed paths with, among others, Cândido Portinari, Roberto Burle-Marx, and Di Cavalcanti, collaborating with Sérgio Bernardes on one of the pavilions for the celebrations of the IV Centenary of the city of São Paulo.

Returning to Lisbon, where Menez (the artistic name of Maria Inês Carmona Ribeiro da Fonseca) became his life and work companion in 1958 for the eight years of their relationship, Anahory began the most productive period of his career. Participating in projects by (other) architects, or establishing agreements/partnerships with them when the signature of a architecture diploma holder was needed (even though he independently and fully developed the projects), the list of collaborations not only traces a map of Anahory’s elective affinities but also, above all, constructs a panorama of what we could call his architectural affiliation, shaped by his prior Brazilian experience. This includes figures such as Pedro Cid, Alberto José Pessoa, Ruy Jervis D’Athouguia, Daciano Costa (with whom he would later fall out over the project for the Gulbenkian Foundation), Raul Chorão Ramalho, Filipe Nobre de Figueiredo, José Segurado, Sommer Ribeiro, Alzina de Menezes, Erich Corsepius, and Raul Tojal.

Anahory’s universe thus represents a transatlantic meeting between modern perspectives that departs from Brazil Builds (GOODWIN, 1943) to arrive at the Verdes Anos (TOSTÕES, 1997).

This period of intense activity corresponds, as will be seen later, to an equally intense presence of Anahory’s work in the specialist press, particularly international, to which he also contributed as a correspondent, adding a new dimension to this network of relationships. His friendship with Gio Ponti, the director of the Italian magazine Domus, is well known, and as a correspondent for the French L’Architecture d’Aujourd’Hui he would certainly have met André Bloc, its founder. It is also known that Sir Paul Reilly, president of the British Council of Industrial Design, had lunch with Anahory at Casa Aiola [7],

his holiday home in Galapos, Serra da Arrábida, and contributed to preventing the first attempt at its demolition, following the questionable legality of its construction, in the early 1960s.

Lisbon, New York, Rio, Paris, São Paulo, and Milan were, then, the hubs of this unique constellation of relationships that Eduardo Anahory knew how to weave, nurture, and maintain, reflecting a truly cosmopolitan spirit, at the centre of which he shone.

2.2 Eclipse

Eduardo Anahory’s architectural work, with the notable exception of his holiday home in Galapos, Casa Aiola, and, to a lesser extent, the Hotel do Porto Santo, is today conspicuously absent from critical reflections on Portuguese architectural production of the 1950s and 1960s, decades during which Anahory created the core of his architectural work. This omission, which can be considered partially reflected in the circumstances that Graça Correia (CORREIA, 2018) details regarding the critical disappearance of the work of his contemporary — and friend — Ruy Jervis D’Athouguia [8], alongside the transience characteristic of some of the programs and construction forms Anahory addressed in his practice, and the aforementioned need to rely on the signatures of architect friends to license his projects (leading to equivocal attributions) [9], contrasts with the international exposure his work received during those same decades.

“In fact, his works were frequently published from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s. Notably, they appeared in almost every issue of the magazine L’Architecture d’Aujourd’Hui between 1958 and 1965, with the exception of 1960 and 1964, when his work was not published in any edition, though it was featured twice in 1962 and 1963. In Domus, his work appeared in one issue per year from 1960 to 1966, except for 1965. In 1962, his work was also published in the German magazine Moebel Interior Design. […] The following year, 1963, his works were published in Italy in Domus magazine, in France in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’Hui, in Germany in a magazine called DBZ – Deutsche Bauzeitschrift, and in England in the Architectural Review, in Switzerland in Bauen+Wohnen, and in Brazil in Arquitectura. In 1965, as noted, his work was featured in France in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’Hui, and also published in the UIA (Revue de L’Union Internationale des Architectes). Despite not being published in Domus that year, it was published in Lotus International (Italy) and was again featured in Germany in DBZ and in Switzerland in Bauen+Wohnen. In addition to these magazines, Casa Aiola was published in the German magazine Neue Wohnhauser, the French Connaissance des Arts, the Swiss magazine 33 Architekten – Einfamilienhauser, and even reached the USA via House Beautiful. It was also featured in the book Vacation Houses: an International Survey by Karl Kasper (New York, Praeger, 1967) (EMÍLIA; FURTADO, 2012: 3).

In a field defined by a lack of criticism and research, “Eduardo Anahory, percurso de um designer de arquitectura [Trajectory of a designer of architecture]”, a dissertation by José Borges for a Master’s degree in Architecture (2010), stands out as the main, and almost only [10], “contribution to the study of the kaleidoscopic architectural and artistic production of this singular author, contextualizing it within his unconventional professional trajectory” (BORGES, 2010: 15). It serves as the primary source for the few academic (and other) texts that have addressed, in their specific contexts, the subject of this research: the Seapool, the floating-beach-pool at Tamariz. José Borges briefly describes the project and the background to its realization (ibid: 143-145), situating it within Eduardo Anahory’s body of work, while Susana Lobo, also referencing Anahory’s article in Binário magazine from August 1968, situates it within the broader context of Portuguese seaside tourism plans and specifically within the context of the Estoril casino concession (LOBO, 2012: 1272-1277). The analysis, albeit superficial, by Rafael Gonçalves focuses on the context of sea pools in the coastal resorts of Portugal (GONÇALVES, 2022: 99 – 100).

The absence (or current lack of knowledge) of an archive, or an organized collection of Anahory’s architectural production, makes it difficult, if not impossible, to access primary sources — graphic and/or textual — of his work in general, and of the floating-beach-pool project in particular. The research developed therefore focused on attempting to identify, as exhaustively as possible, previously unexplored sources, particularly in the daily press, which helped fill gaps in the still incipient chronology of the project — first, its realization, then, its materialization; and, finally, its reinstatement. We also contacted the Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial [National Institute of Industrial Property], and its indications enabled us to locate international patents. The RTP Archive was also consulted, and two films were found, related to the press visit and the inauguration of the pool, that are now made available on its website. Additionally, the Direção Geral do Território provided a low-resolution aerial photo from 16 September 1970, the only one taken during the three summers the pool was installed (and whose absence on that date highlights the short duration of its use). The Estoril Casino Museum, which holds the archive of Sociedade Estoril-Sol, the promoter of the floating-beach-pool, was also contacted. However, it has not indicated any interest in or availability to support the research. Among the documentary sources thus identified, the most notable are the patent registrations — in France, Australia, and Brazil — and films from the Portuguese Radio and Television Archive, because they are so far unpublished and also due to the relevance of the information they directly and indirectly reveal. It was also possible to add to the above list of international publications (BORGES, 2010; EMÍLIA; FURTADO, 2012), number 469 of Domus magazine (December 1968 [11].

For this article, we also conducted two interviews: one with Graça Anahory Vasconcelos, Eduardo Anahory’s niece and occasional collaborator, and the other with the architect Ana Tostões, who supervised José Borges’ master’s thesis, and, among other roles, was the director of the PhD program in Architecture at the Instituto Superior Técnico. They both frequented the Seapool.

3. MORE IODINE

3.1 Nostalgia for the sea: an idea for multiple places

“At school one day, a student designed a floating swimming pool. Nobody remembered who it was. The idea had been in the air. Others were designing flying cities, spherical theaters, whole artificial planets. Someone had to invent the floating swimming pool. The floating swimming pool — an enclave of purity in contaminated surroundings — seemed a first step, modest yet radical, in a gradual program of improving the world through architecture. To prove the strength of the idea, the architecture students decided to build a prototype in their spare time. […] The prototype became the most popular structure in the history of Modern Architecture” (KOOLHAAS, 1994: 307).

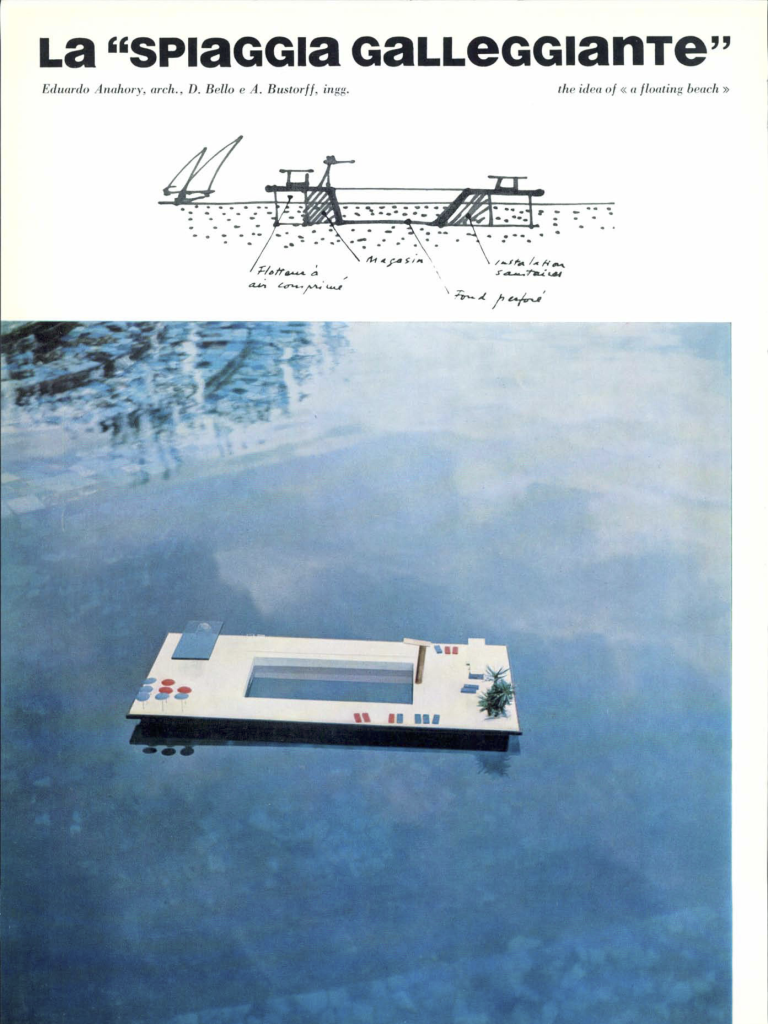

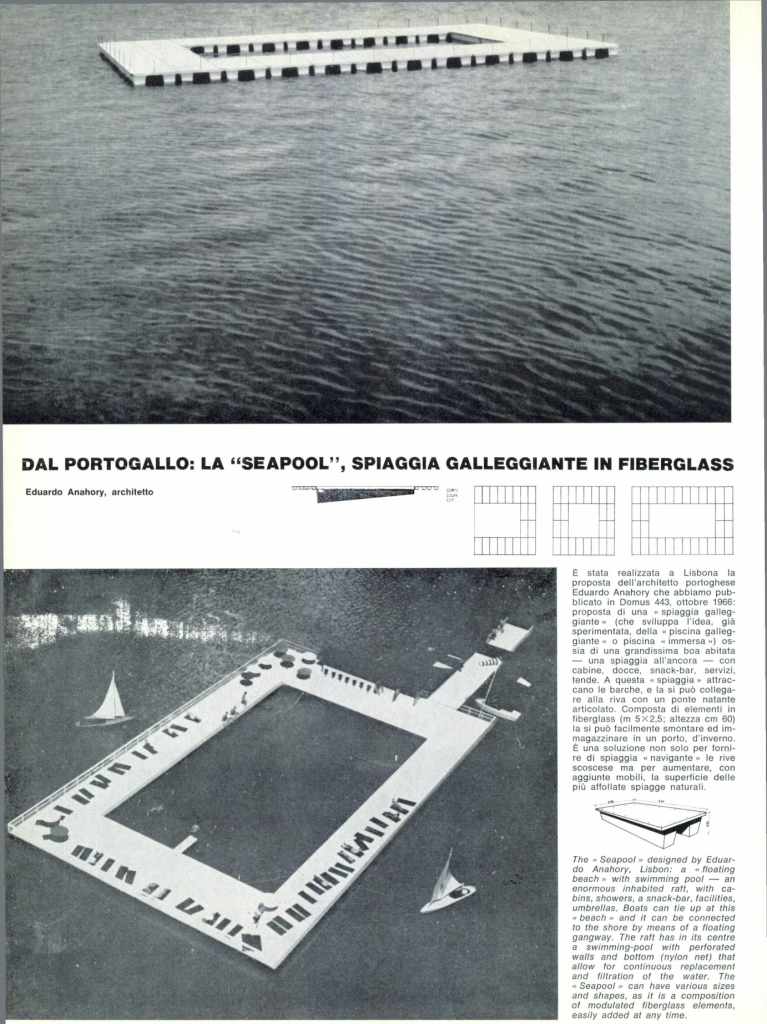

Figure 3 – The floating-beach-pool in Domus magazine, 1966 (Source: Domus No. 443. Milan, October 1966, p. 32).

The project for the floating-beach-pool, or more accurately, the idea of a floating-beach-pool, first appeared on pages 32 and 33 of issue No. 443 of the Italian magazine Domus in October 1966, just a few months after Eduardo Anahory, along with engineers Duarte Belo and António Bustorff Silva, had registered, from Lisbon, a patent which would be accepted and published in France in the Bulletin officiel de la Propriété industrielle only in May 1968 [12].

In contrast to the diffuse genesis of the imaginary floating swimming pool by Koolhaas’ russian constructivists, Anahory precisely describes the origin of his idea: it was born a few years earlier (1965) during the design process of a hotel in the Algarve, where the site ended in cliffs 30 metres above the sea [13]:

“In view of this, we considered building a large saltwater swimming pool, which seemed like a solution. However, after building a model of the ensemble, we realized that the pool looked like a small tank lost in the heights: it lost its direct connection with nature, and there was no real presence of the sea, which bathers would gaze at from afar with understandable nostalgia… That’s when the idea of placing the pool within the ocean and in the natural environment was born.”(ANAHORY, 1968: 79).

The Domus article, illustrated with an expressive photograph of the model and a hand-drawn schematic cross-section, describes this ‘floating beach’ as “an enormous inhabited raft — a anchored beach — with cabins, showers, snack bar, toilets, umbrellas, a pool (for the inexperienced and children), […] a kind of ‘station’, an advanced base, in the sea” (translated from the Italian).

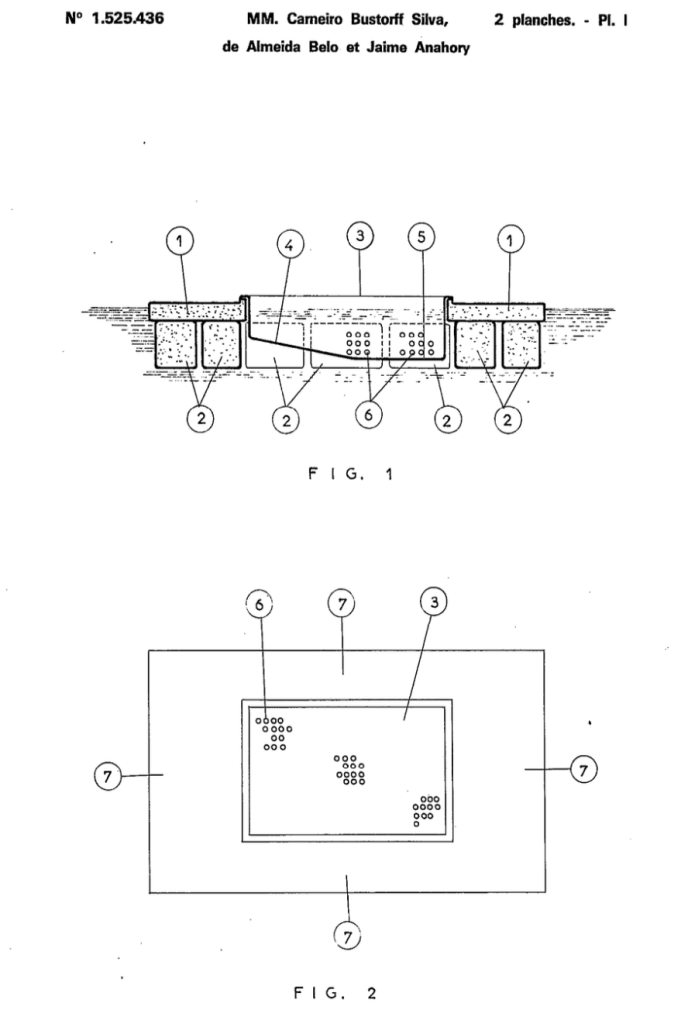

Figure 4 – Drawings for the French patent (1966). Reproduced from: Brevet d ‘Invention: Plage Artificielle Flottante, Ministère de L’Industrie, Service de Propriété Industrielle, 1968 (Source: European Patent Office: https://worldwide.espacenet.com).

According to the Brevet d ‘Invention [Patent],

“the artificial floating beach according to the invention consists of a platform 1 [numbering refers to the legend of the drawings accompanying the patent], preferably generally rectangular in shape, made of any suitable material, and capable of being constructed from removable elements for ease of transport or storage. The platform 1 is supported by floats 2, consisting of boxes that can be removably mounted underneath the bottom of the platform. The platform 1 includes a substantial opening in its centre in which a tank 3 is housed. The bottom part 4 of the tank is sloped, and its side walls may be made of perforated panels 6. The bottom may also be perforated with holes to allow water to enter the tank, ensuring a constant water level, and, due to the perforations, the water can be automatically renewed without the need for filling or draining devices. Zone 7 of platform 1 is intended to accommodate a terrace, bar, restaurant, resting area, etc.” (SILVA; BELO; ANAHORY, 1968 [1966] (translated from the French).

Designed to be seasonal (but not ephemeral), movable, transportable (on land and at sea), and storable, and intended to “serve not only where there are no beaches but also where they are difficult to access […] or have marine fauna that is somewhat unsettling […] and, additionally, in areas with good beaches, but which are usually overcrowded, offering neither space nor tranquillity” (ANAHORY, 1968), the invention was not limited to use in coastal areas but also in areas bathed by water bodies — rivers, lakes, lagoons, etc. — where this floating artificial beach can be used. It “therefore serves a useful purpose as, in the landscape of certain regions, it is a complement for enabling tourist development” (SILVA; BELO; ANAHORY, 1968). According to the inventors, this was the case in Portugal, with its vast Atlantic coastline, but where “only a few sandy beaches allow the creation of bathing facilities” (translated from the French).

A second patent, now signed solely by Eduardo Anahory, was submitted to the Australian intellectual property authority in September 1968 and published in April 1970 [14]. Whether motivated by the potential publication of the floating-beach-pool in that region, and/or by the departure of one of his collaborators to that continent (BORGES, 2010: 116), the fact is that, although it retained the drawings that illustrate it from the original patent, the description of the invention, in addition to adapting to the local culture (for example, referencing the practice of surfing and the presence of sharks along the Australian coast), this patent includes more detail and developments in its technical specifications, certainly reflecting the evolution of the idea into the realm of practical implementation [15]. The description now allows for configurations other than strictly rectangular, with clearer references to the modularity of the constituent parts and their inter-adjustability. It also proposes alternative options for the delimitation of the open tank in the centre: in addition to perforated panels, there is the possibility of using a metal mesh, either as an alternative or in a mixed-use combination.

Susana Lobo suggests that “Anahory’s proposal is nothing more than a reinterpretation, updated and using the most recent technology associated with construction, of the old Barcas de Banhos [Bathing Barges] anchored in the Tagus River” (LOBO, 2012: 1273). However, while we can also place these in the same hygienist (and recreational) lineage of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, we believe Anahory’s references were both closer in time yet more distant geographically: the New York floating baths and the Parisian Piscine Deligny. This hypothesis is made plausible by Anahory’s statement in the article he published in 1968 in Binário (ANAHORY, 1968: 79), where he mentions that “private consultations” were conducted in the United States and France during the design process.

Figure 5 – Piscine Deligny, 1968 (Source: Diário de Noticias. Year 104 No. 36726, 02/07/1968, p. 1).

Indeed, it is likely that, during his visit in 1939, Anahory encountered the last floating baths of New York, which were still moored during the summer months along the piers that lined the entire waterfront of Manhattan (BUTTENWIESER, 2021: 52-53). Similarly, during his Parisian stays, he may have come across — or even frequented — the venerable, fashionable, and floating Piscine Deligny, where, in the 1960s and 70s, the fashionable crowd of Paris, le tout-Paris, gathered to sunbathe and parade the monokini (MESNARDS, 2023), and which graced the banks of the Seine from 1785 until it sank in 1993 [16].

However, one thing remains unchanged: what is novel about Eduardo Anahory’s idea is that it is a beach. A floating beach, in the centre of which there is space for a swimming pool. A pool that results from enclosing a volume of water within the sea itself.

To paraphrase Koolhaas, it is a modest yet radical idea.

3.1 Offshore: a cosmopolitan and elegant staging

After its publication in Italy in the magazine Domus, the floating-beach-pool made its first national appearance in the pages of Diário de Lisboa on July 16th 1967. Illustrated with a more detailed version of the perspective that accompanied both the patents previously mentioned, this article is, the following year, credited by Anahory with the responsibility, alongside the publication in Domus, for sparking the interest of Sociedade Estoril-Sol in sponsoring the creation of a prototype, in exchange for priority access to its use. (ANAHORY, 1968: 79).

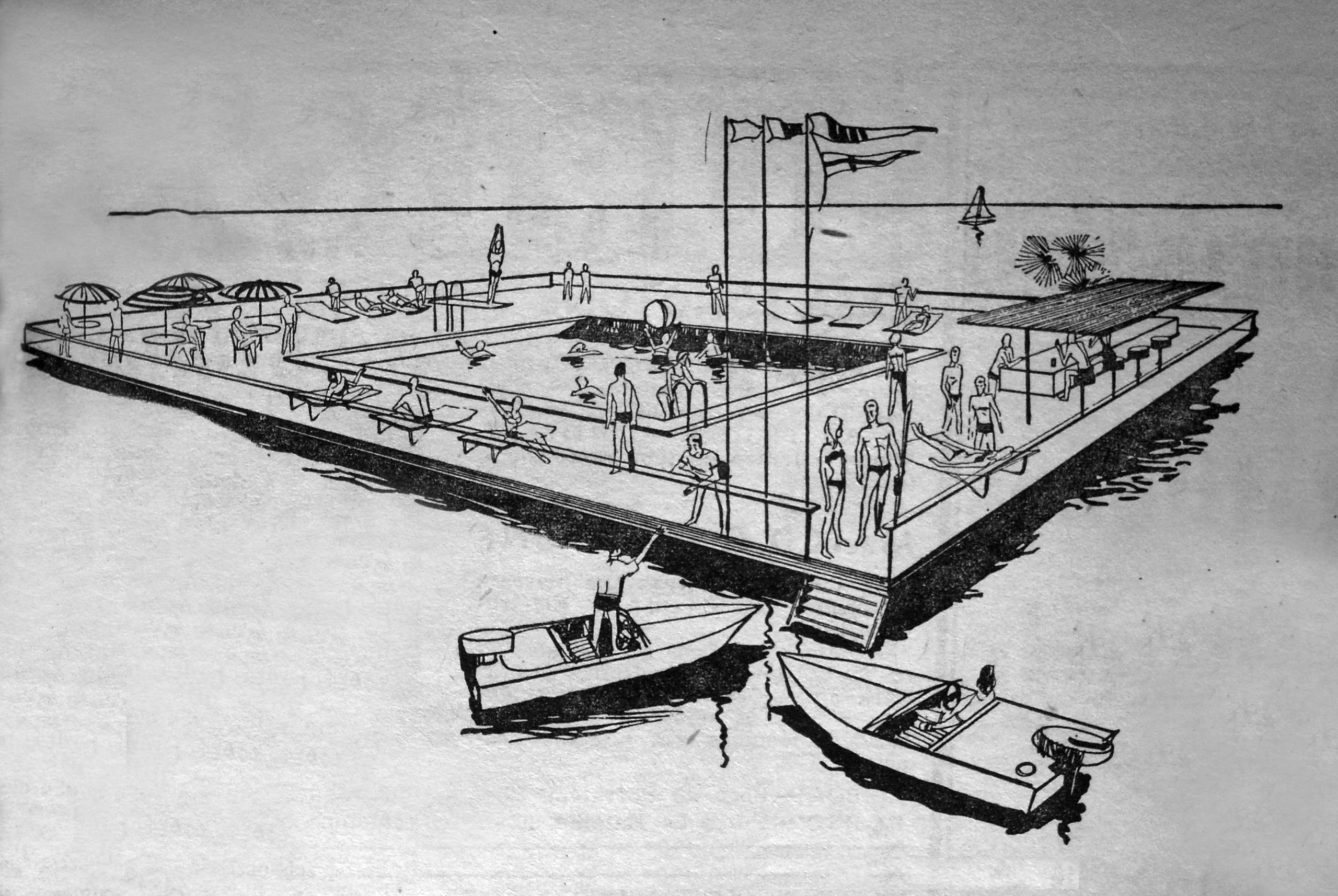

Figure 6 – Floating beach pool project perspective, 1967 (Source: Diário de Lisboa. Year 47 No. 16011, 16/07/1967, p. 13).

Holder of the Estoril gambling concession since 1958, the Sociedade Estoril-Sol inherited not only the old Casino Estoril but also the new Tamariz swimming pools, designed by Manuel Tainha and inaugurated in 1956. In compliance with the concession obligations, the company opened the Hotel Estoril-Sol in 1965, designed by Raul Tojal. This was followed in 1968 by the renovated and expanded Estoril Casino, designed by Filipe Nobre de Figueiredo and José Segurado, and, in the summer of the same year, the new Tamariz Beach Bathing Establishment, designed by José Pinto dos Santos. Meanwhile, construction of the Monte Estoril–Cascais stretch of the seaside promenade, for which the government was responsible, fell behind schedule. The final section of a project begun in 1950 was only completed in 1970.

Given the Sociedade Estoril-Sol’s pattern of selecting a specific set of architects for its projects, its interest in Eduardo Anahory’s floating-beach-pool project, not mandated by the concession but within the spirit of modernizing its facilities, seems natural in that context.

Figure 7 – Eduardo Anahory, and Ticiano Violante presenting the floating-beach-pool project to the press, 1968 (Source: unidentified publication. Image courtesy of Luiza Carrelhas Albuquerque).

Once the support for the construction of the prototype was secured, the floating-beach-pool was presented to the national daily press on July 17th 1968, at the invitation of Eduardo Anahory, around a model created by Ticiano Violante [17]. The news (which refers to Anahory as artist), published in Diário de Lisboa, Diário Popular, A Capital, Diário de Notícias, and an unidentified evening newspaper [18], describes the project in roughly the same terms as it is described in its first patent, suggesting that Anahory and/or the Sociedade Estoril-Sol may have provided a press release to journalists. New is the information included in the articles that the prototype will have an external dimension of 30 x 20 metres, with the pool inside measuring 20 x 10 metres, totalling 200 m² of water surface and 400 m² of deck space, with a capacity to comfortably accommodate 100 people. It is also stated that the prototype is expected to be installed in front of the Hotel Estoril-Sol, at an estimated cost of six hundred to eight hundred thousand Portuguese escudos [19].

It also states that the project would be developed in collaboration with the firm of Alzina de Menezes and Erich Corsepius.

In August of the same year, Anahory published the article praia-piscina-flutuante on page 79 of No. 119 of Binário: Arquitectura, Construção, Equipamento magazine (ANAHORY, 1968). This seems to be the only contemporary appearance of this project in the specialist architecture press in Portugal, illustrated only with a sketch of a section and a perspective (despite the existence of the aforementioned model). Given the information it contains, the article might be the same text, or a version of it, which we speculate was provided to journalists the previous month

Another abbreviated trilingual version (Portuguese, French, English), of the same text was also published in August on pages 20 and 21 of issue no. 268-269 of the tourism magazine Lisbon Courier. It featured a photograph of the model produced by Violante and a new sketch representing a section of the structure, with one particular detail: a reference (the first and only) to the use of a “plastic bottom” associated with the nylon mesh that defines the vertical boundaries of the pool, which suggests that the project still had open design options.

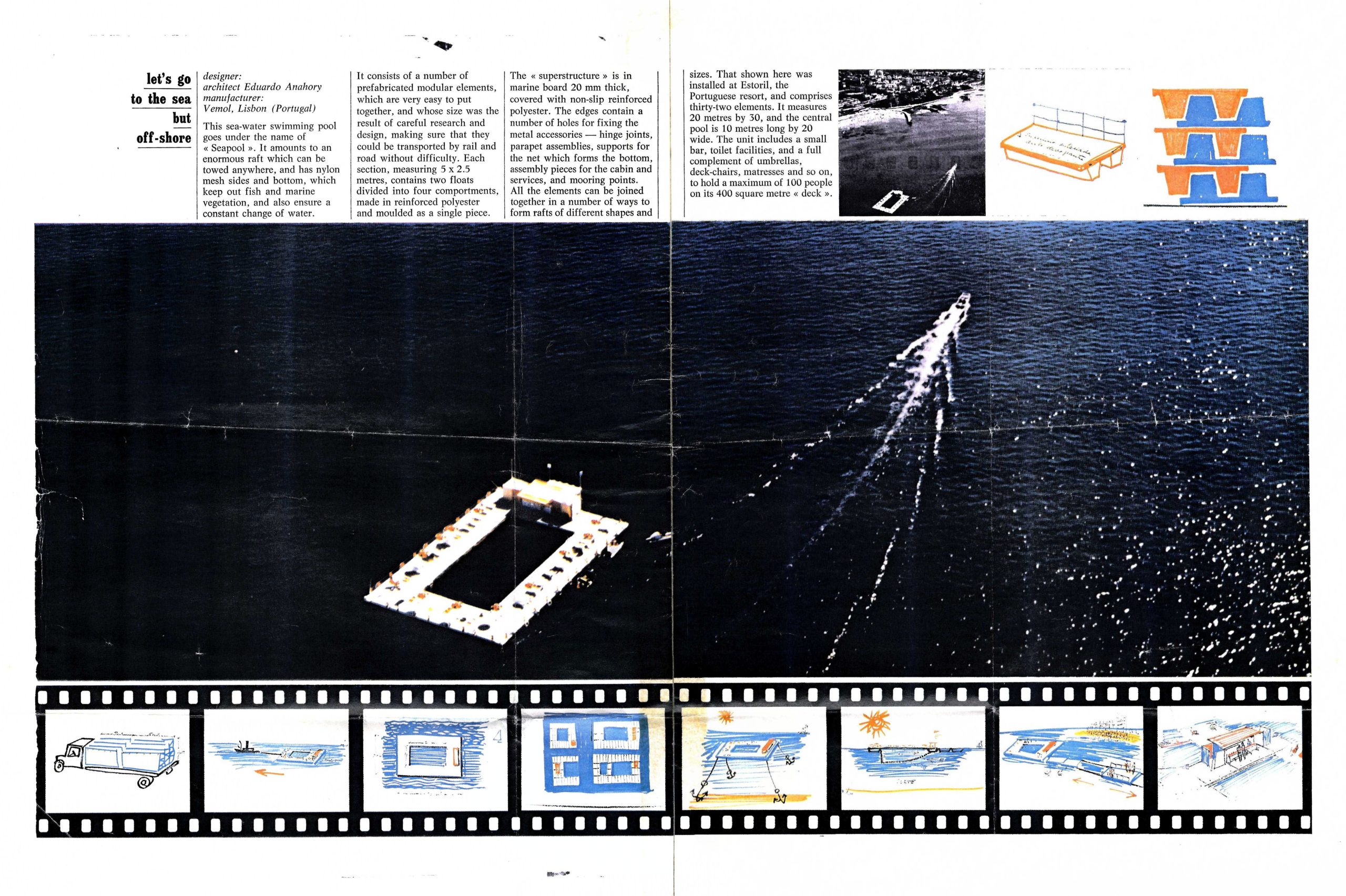

Figure 8 – The prototype and model of Sea pool in Domus, 1968 (Source: Domus no. 469. Milan, December 1968, p. 32).

However, the project and the production of the prototype seems to have advanced rapidly, as, in addition to the progress already identified in the description of the Australian patent, a second publication in Domus magazine, on page 32 of issue no. 469 from December 1968, is significantly illustrated, not only with the same photograph of the model published in the Lisbon Courier, but also with a photograph of the prototype floating on a body of water, and a set of schematic technical drawings. In what is the first reference to the name Seapool, the text informs us that it is “composed of fibreglass elements (5 x 2.5 m; 60 cm high) [and] can easily be dismantled and stored in a winter harbour” (translation from the Italian). The photograph of the prototype also makes it possible to see, by counting the constituent elements and now knowing their dimensions, that it was built with the announced size of 30 x 20 metres and that it includes supports for a guardrail around its perimeter.

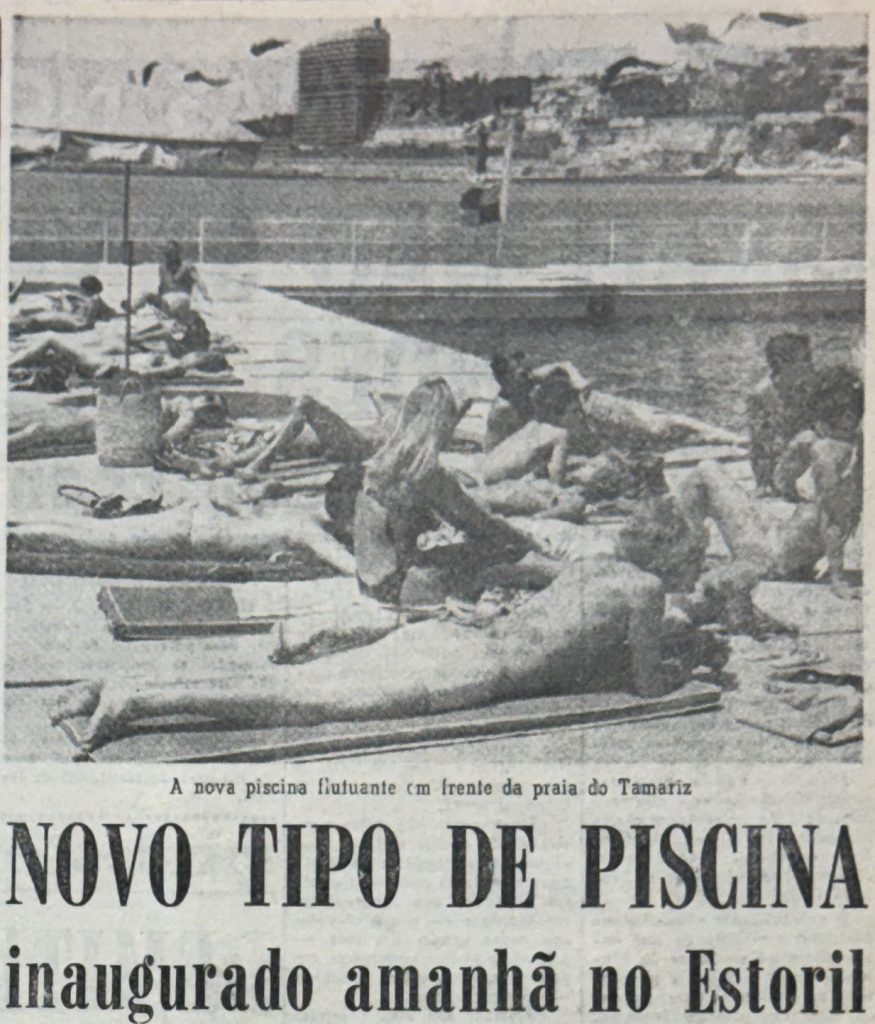

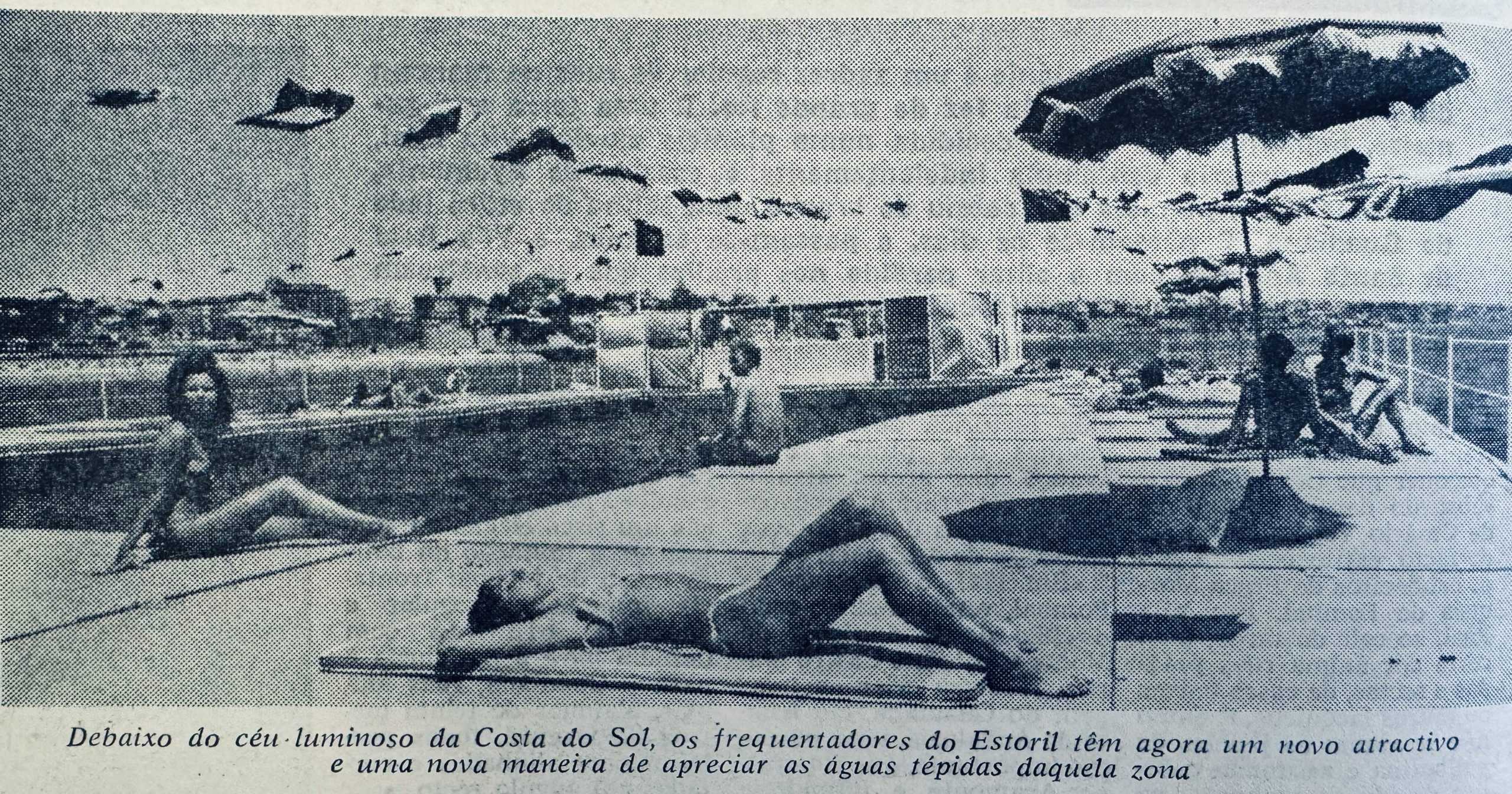

After a hiatus of almost two years, the reason for which we can only speculate, the Seapool was finally inaugurated at the beginning of July 1970. The press was invited by Sociedade Estoril-Sol for a preview visit at 10:30 a.m. on July 2nd, followed by the official inauguration at 6:00 p.m. on July 3rd. The Secretary of State for Information and Tourism, César Moreira Baptista, opened the pool to the public the following day.

Figure 9 – Inauguration of the Seapool, 1970 (Source: Diário Popular. Year XXVIII, no. 9950, 07/02/1970, p. 23). Diário Popular. Year XXVIII No. 9950, 02/07/1970, p. 23).

The text of the features in the newspapers A Capital, Diário de Lisboa, Diário Popular, O Século, República, Diário de Noticias, Jornal da Costa do Sol, and The Anglo-Portuguese News once again appeared to have borrowed from a press release provided by the organizers. It informs us that representatives of the press visited the first-floating-beach pool, a model “designed and patented” by Eduardo Anahory, who “baptised” his invention Seapool. It was located approximately 300 metres offshore from the Tamariz beach.

“The ‘raft’ consists of modular elements, which are very easy to assemble, disassemble, and store. Each module is 5 metres long and 2.5 metres wide, weighing approximately 400 kilograms. Therefore, the size of the ‘Seapool’ will depend on the number of modules it consists of. The one installed at the Tamariz beach has external dimensions of 30 by 20 metres […]. Surrounding the pool is a large ‘deck,’ covering an area of 400 square metres, which comfortably accommodates 150 people, in addition to a snack bar and sanitary facilities. Connected to each other, the modules of the ‘Seapool’ are made of reinforced polyester floats with fiberglass mesh. The upper part of each, forming the ‘deck,’ is made of waterproof Hambala [sic] plywood with an anti-slip granulate coating. The pool’s stability is ensured by two floats along its entire length (catamaran system). Additionally, each element of the pool, even when floating individually, can support ten people on the same edge without the risk of capsizing and can also bear a load of up to two thousand kilograms without sinking. […] To bring his idea to life, Eduardo Anahory secured sponsorship from the Sociedade Estoril-Sol, at whose Alcoitão shipyard this prototype was built. […] The journey between the Tamariz beach and the floating pool is made by a gasoline boat from Estoril-Sol, which will maintain regular connections” [20] [21].

Interestingly, only The Anglo-Portuguese News mentions the price for using the Seapool: 40 escudos for women and 50 escudos for men on weekends; 30 escudos for women and 40 for men on weekdays. This omission in other papers may be due to the pricing being inaccessible to most of the population [22], and publishing it in widely circulated newspapers could have negatively affected the perception of the floating-beach-pool.

Figure 10 – Let’s go to the sea, but off-shore (n.d.) (Source: unidentified publication. Digital copy provided by José Borges, originally from the archive of a former collaborator of Eduardo Anahory}.

The article entitled Let’s go to the sea, but off-shore, whose original publication could not be identified, adds further technical details about the Seapool’s construction system. Each module, manufactured by the Vemol [23], company, consists of two floats divided into four compartments, made of reinforced polyester moulded as a single piece. The edges of each module have recesses for fitting metal accessories, such as:

articulated connection pieces between the modules, attachments for the net enclosing the walls and bottom of the pool, fixtures for the peripheral guardrail, mounting components for the bar and restroom facilities, and anchoring and mooring points.

This design not only allows the modules to be combined in several ways to form rafts of different shapes but also demonstrates the conceptual sophistication of Anahory’s project, displaying a clear mastery of construction using prefabricated elements.

In addition to drawings illustrating the different possibilities for transporting and assembling the Seapool, the article also includes an aerial image of it, though it cannot be definitively stated that this is an actual photograph, as it might be a photomontage. Nevertheless, it allows one to envisage its location (real/desired) off the Tamariz.

Figure 11 – The Seapool, 1970 (Source: A. Capital. Year III No. 846, 02/07/1970, p. 8).

Regarding the visual communication of the Seapool, it is noteworthy that, with the exception of the July 3rd edition of O Século, which published a photograph effectively taken during the press representatives’ visit, all other newspapers illustrate their reports with photographs that were likely provided by the Sociedade Estoril-Sol. This can be verified by comparing these images with the video report from RTP [24] of that visit. Indeed, when viewed from the beach, approximately 300 metres away, the Seapool looked rather unremarkable, with its deck elevated less than 60 cm above the sea surface. The colourful elements of the bar structure, as well as the flags and umbrellas, sought to counteract this, suggesting that Anahory and Sociedade Estoril-Sol might have intended to convey a more appealing image. However, a closer examination of this collection of photographs reveals their deliberately staged nature: slender bodies (perhaps members of the casino’s dance troupe?) in relaxed poses, wearing bold bikinis and swimsuits, constructing a cosmopolitan narrative of pleasure and even a certain hedonistic abandon, that stands in stark contrast to the reality of the country outside the tourist and social bubble of Estoril during those decades. These images, now, to our eyes, appear, in what could be classified as a subtly subversive act, to assert the Seapool as a place offshore: from both the beach and the country.

The Seapool became a gathering place for the same “beautiful people” who frequented the elegant nightlife of Cascais and Estoril [25], of which was, in some sense, the sunny counterpart. With its intended seasonal existence — though it turned out to be ephemeral — the Seapool managed to create a kind of happy heterotopia, a (privileged, it must be admitted) space of sophisticated, prelapsarian freedom. A bohemian and chic freedom, common characteristic of the places constructed by Eduardo Anahory. (BORGES: 2010: 56).

Figure 12 – Announcement of the reopening of the Seapool, 1971 (Source: A Capital, year IV No. 1211, 09/07/1971, p.12).

Apart from an article in the October 1970 edition of Lisbon Courier (issue 294-295), which mentions that “despite the high number of users and having occasionally withstood strong winds and swells, [the Seapool] did not suffer any damage to its components” and that “now dismantled and stored, will be reinstalled next summer,” there seems to have been little coverage in either general or specialist press regarding its reception

In the summers of 1971 and 1972, the Seapool was once again set up off the Tamariz beach, as evidenced by the announcements of its reopening in the newspapers A Capital, Diário de Lisboa, Diário de Notícias, Diário Popular, and O Século. In 1972, a price reduction was announced, possibly to attract more visitors after the initial novelty had worn off. It will have been its last summer.

4. MORE SEA

4.1 Ocean-chart: topos and locus

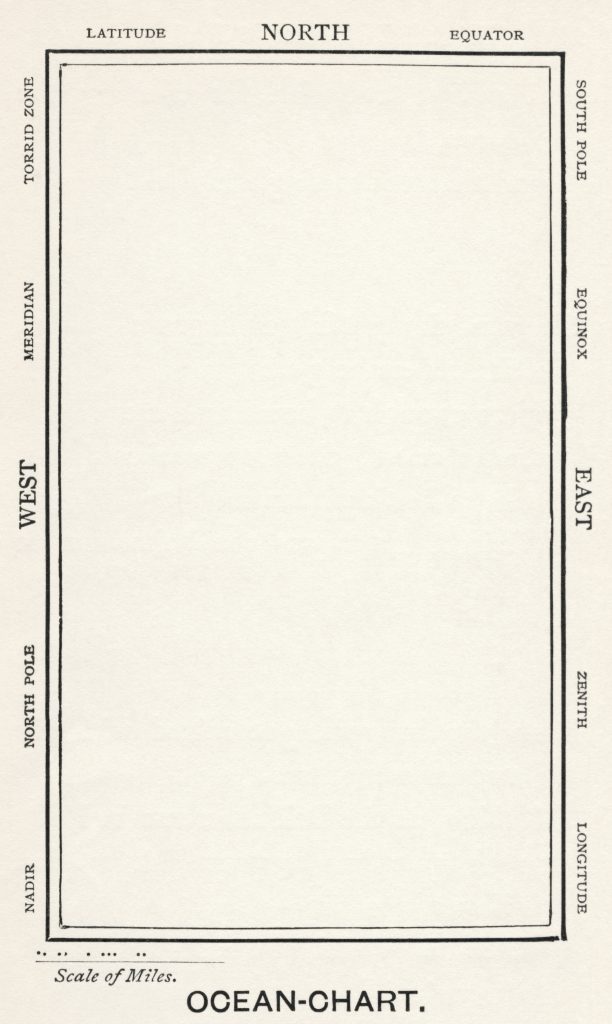

“He had bought a large map representing the sea,

Without the least vestige of land:

And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be

A map they could all understand.

‘What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?’

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

‘They’re merely conventional signs!’

‘Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

But we’ve got our brave Captain to thank’

(So the crew would protest) ‘that he’s bought us the best —

A perfect and absolute blank!’” (CARROLL, 1876).

The modest radicality of the concept of the floating beach-pool is most intensely expressed in the act of inscribing a boundary that encloses a surface (and a volume) of water within the vastness of the sea. Experiencing this stretch of sea, delimited within (and in view of) the expansiveness of the sea itself, would then have configured a possibility of a synecdochic experience, pars pro toto: a kind of intense condensation of the immeasurability of the whole.

Figure 13 – Ocean-Chart, 1931 version of the illustration of Lewis Carroll’s poem The Hunting of the Snark, 1876 ( Available at: wikimedia.org).

Carroll’s satirical example, cited above, of a sea map, an Ocean Chart, which shows us just that, the sea, nonetheless refers to the Augustinian conception that “to make the immeasurability of space workable, space had to be experienced from a point at the centre” (ABEN; DE WIT, 1999: 48). In other words, the way we can comprehend and deal with the infinity of space is by dividing it into measurable finite portions (ibid: 160).

The act of delineating boundaries, as an attempt at understanding, is an operative process — drawing from both vernacular and scholarly traditions — that is frequent in the construction of (and within) the Landscape. Indeed, “etymologically, physically, and ontologically, the garden is an enclosure: an entity carved out of a territory […], individualized and autonomous” (BRUNON; MOSSER, 2005: 321).

As an artefact inscribed within a territory, the Seapool enacts a transfiguration that we can analyse through this very conceptual lens. It is constructed “in relation to, within, and by opposition to the Landscape in which it is inscribed, [it] delimits itself within it and from it, condenses it, isolates, and re-contextualizes the elements that compose it…”(BEIRAMAR DINIZ, 2006: 56). Thus, it can be metonymically understood as an (other) form of hortus: an hortus aqueus or an hortus oceanicus.

On an archetypal topos, the Sea, Anahory, by operating a concentration of identity (KLUGE, 2011: 21), inscribed, in this measure, a locus— a “place of existence, where one is, where on is at, where one creates and builds occasions and opportunities to inhabit” (CARAPINHA, [2006]: 65).

4.1 Seapool: an artefact-event

Gérard Monnier defines the “building-event” as a structure that “implies the large-scale use of information techniques, thus entering forcefully and suddenly into the public space (in the sense defined by Habermas) to establish a meaningful representation there” (MONNIER, 2005: 294). In his typology for characterizing the building-event within contemporary architectural history, Monnier distinguishes between two types: the ‘occurred’ building-event and the ‘programmed’ building-event (ibid: 296) [26].

The latter encompasses various categories — such as the grand building, the temporary building, the symbolic building, the famous project, the voluntary destruction, and the polemical event. Of particular interest here is the second category, the temporary building, and the potential to apply this conceptual framework to examine the floating-beach-pool and its inclusion in a constellation of affinities. Recognizing its ambiguous disciplinary classification — spanning architecture, design, and landscape — it follows that, strictly speaking, the Seapool cannot be characterized as a building. We therefore propose, for operational purposes, adopting the term “artefact-event”.

The analysis in the previous chapters of the deliberate and clearly planned communication process — first of the idea, then of the project’s realization — allows us to retrospectively situate the Seapool within Monnier’s adapted definition of an artefact-event, while maintaining the necessary distance imposed by a time preceding the present development of mass communication. Nevertheless, Eduardo Anahory, initially on his own and later with the support of the Sociedade Estoril-Sol, clearly made use of information techniques on a scale, and with an expertise, uncommon in architectural communication of his era, not only in Portugal, assertively placing his project in the public discussion space, seeking to establish a meaningful discourse there.

The Seapool, despite its uniqueness, is not alone in what we might call the floating subcategory of contemporary artefact-events. To construct a possible constellation of affinities, we must include, in chronological order, the following notable examples: Robert Smithson’s Floating Island to travel around Manhattan Island (1970-2005), The Floating Piers by Christo and Jeanne-Claude (1970-2016), the aforementioned floating swimming pool from Delirious New York by Rem Koolhaas (1978), Aldo Rossi’s Teatro del Mondo for the first Venice Architecture Biennale (1979-1980), and Ann L. Buttenwieser’s Floating Pool Lady in New York (2007).

Eduardo Anahory, with his remarkable ability to capture the spirit of his time, created an artefact-event even before these had been formally conceptualized. Today, it would likely achieve much sought-after viral status: the Seapool would be, for 15 minutes, “the most popular structure in the history of Modern Architecture” (KOOLHAAS, 1978: 307).

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Anahory’s unique trajectory in Portuguese architecture, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s, finds a peculiar synthesis in the Seapool, the floating-beach-pool for Tamariz beach, despite, or perhaps because of, its typological and even disciplinary ambiguity. Example of a method of approach to the design process (including creating its opportunity), that seamlessly integrates the mastery of spatial conception, technical design, and fabrication methods ranging from artisan craftsmanship to industrial prefabrication. with the mastery of communication processes, Anahory’s body of work blurs various boundaries, approaching the possibility of a total work of art.

Equally unique is Anahory’s clear perception of the technical innovation inherent in his explorations for each project, and that is reflected in the various patents he registered, extending beyond the specific Seapool project.

The full scope, both material and conceptual, of his work remains, still, largely unexplored, and its rightful place in the history of contemporary architecture is yet to be reestablished. This research aims to take a step in that direction.

Bibliography

ABEN, Rob; DE WIT, Saskia — The Enclosed Garden, History and Development of the Hortus Conclusus and its Reintroduction into the Present-day Urban Landscape. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1999.

ANAHORY, Eduardo — “praia-piscina-flutuante.” Binário, Arquitectura, Construção, Equipamento. Nº 119. Lisbon, August 1968, p.79.

BEIRAMAR DINIZ, Victor — E o jardim, como tudo o resto, estava deserto. In ADRIÃO, José; CARVALHO, Ricardo (ed.) — Jornal Arquitectos. Nº 224. Lisbon, July-September 2006, pp. 56-58.

BORGES, José António Brás — Eduardo Anahory, percurso de um designer de arquitectura. Lisbon: Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, 2010. Master’s dissertation.

BRUNON, Hervé; MOSSER, Monique — L’enclos comme parcelle et totalité du monde: pour une approche holistique de l’art des jardins. In THOMINE-BERRADA, Alice; BARRY, Bergdol (ed.) — Repenser les limites: l’architecture à travers l’espace, le temps et les disciplines: 31 août – 4 septembre 2005. New edition. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2005. pp. 321-332. Available at: http://books.openedition.org/inha/30 [Consult. 26/05/2024].

BUTTENWIESER, Ann L. — The Floating Pool Lady: A Quest to Bring a Public Pool to New York City’s Waterfront. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021.

CARAPINHA, Aurora — Paisagem – Vínculo Relacional. In AFONSO, João (ed.) — Inquérito à Arquitectura do Século XX em Portugal. Lisbon: Ordem dos Arquitectos, n.d. [2006], p. 65-66.

CARROLL, Lewis — The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony in Eight Fits. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1876.

CORREIA, Graça — Ruy D’Athouguia. Porto: Edições Afrontamento, 2018.

Dal Portogallo: la “seapool,” spiaggia galleggiante in fiberglass. In MAZZOCCHI, Gianni (ed.) — Domus. Nº 469. Milan, December 1968, p.32.

EMÍLIA, Cristina; FURTADO, Gonçalo — Ideias da Arquitectura Portuguesa em viagem. In TAVARES, Domingos; COSTA, Alexandre Alves (coord.) — Joelho 03: Viagem-Memória: Aprendizagens de arquitectura. Coimbra: Edarq, 2012.

GONÇALVES, Rafael José de Sousa — As Piscinas de Mar no planeamento das estâncias de vilegiatura balnear portuguesa: reativação da Piscina Oceânica de S. Pedro de Moel. Évora: Escola das Artes, Universidade de Évora, 2022. Dissertação de Mestrado.

GOODWIN, Philip L. — Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old 1652 – 1942 / Construção Brasileira: Arquitectura moderna e antiga. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1943. Available at: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2304_300061982.pdf [Consulted 26/05/24]

GUILHERME, Pedro Hernandez Salvador — O concurso internacional de arquitectura como processo de internacionalização e investigação na arquitectura de Álvaro Siza Vieira e Eduardo Souto de Moura. Lisbon: Faculdade de Arquitectura, Universidade de Lisboa, 2016. Doctoral thesis.

KOOLHAAS, Rem — Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. New York: The Monacelli Press, 1994 (1st ed. 1978).

KLUGE, Alexander — Gardens are Like Wells. In AAVV — Peter Zumthor: Hortus Conclusus, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion 2011. London: Serpentine Gallery and Koenig Books, 2011, pp. 18-21.

La “spiaggia galleggiante”/the idea of a “floating beach.” In MAZZOCCHI, Gianni (ed.) — Domus. Nº 443. Milan, October 1966, pp. 32-33.

Let’s go to the sea but off-shore. Unidentified publication. [197-].

LOBO, Susana — A colonização da linha de costa: da marginal ao «resort». In CARVALHO, Ricardo (dir.) — Jornal Arquitectos. Nº 227. Lisbon, April-June, 2007, pp. 18-25.

LOBO, Susana Luísa Mexia — Arquitectura e Turismo: Planos e Projectos, as cenografias do lazer na costa portuguesa, da 1ª República à democracia. Coimbra: Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade de Coimbra, 2012. Doctoral thesis.

MENDES, Pedro Ferreira — Eduardo Anahory: o arquitecto sem curso. Arquitectura e construção. Nº 70. Paço de Arcos, December-January 2012, p. 66-69.

MESNARDS, Fanny Guénon des — Ski nautique, monokini… La piscine Deligny concurrençait la baignade dans la Seine. AD Magazine. August 2023 Available at: https://www.admagazine.fr/galerie/piscine-deligny-seine-paris [Consult. 14/06/2024].

MONNIER, Gérard— Que faire de l’édifice-événement? In THOMINE-BERRADA, Alice; BARRY, Bergdol (dir) — Repenser les limites: l’architecture à travers l’espace, le temps et les disciplines: 31 août – 4 septembre 2005. Nova edição. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2005, pp. 294-299. Available at: http://books.openedition.org/inha/30 [Consult. 26/05/2024].

“Praia-piscina-flutuante.” In CARVALHO, Frederico (dir.) — Lisbon Courier. Year XXIII, no. 268-269. Lisbon, August 1968, pp. 20-21.

Seapool – Uma piscina flutuante. In CARVALHO, Frederico (dir.) — Lisbon Courier. Ano XXV, no. 294-295. Lisbon, October 1970, p. 14.

TABORDA, Pedro — Reposição da Casa-abrigo Eduardo Anahory: Arrábida, 1960. COELHO, António (ed.) — Infohabitar: A Revista do Grupo Habitar. Nº 168. Lisbon, November 2007. Available at: https://infohabitar.blogspot.com/2007/11/reposio-da-casa-abrigo-eduardo-anahory.html [Consulted 01/04/2024].

TOSTÕES, Ana — Os Verdes Anos na Arquitectura Portuguesa dos anos 50. 2nd Edição. Porto: FAUP publicações, 1997.

TSAI, Eugenie (ed.) — Robert Smithson. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, 2004.

Articles in daily and weekly newspapers

Piscinas-praias flutuantes — uma ideia para zonas da costa sem praia ou para praias superlotadas. Diário de Lisboa. Ano 47º nº 16011, 16/07/1967, p. 13.

Sonho de uma noite de Verão? Jornal da Costa do Sol. Ano IV nº 186, 11/11/1967, p. 1.

Regresso à normalidade: O trabalho recomeça e Paris recupera a fisionomia habitual. Diário de Notícias. Ano 104 nº 36726, 06/06/1968, p. 1,7.

A Praia do Estoril valorizada com as novas instalações balneárias do Tamariz. Diário de Notícias. Ano 104 nº 36730, 07/06/1968, p. 11.

O Novo Estabelecimento de banhos de mar do Estoril. Jornal da Costa do Sol. Ano V nº 217, 15/06/1968, p. 1, 10.

Piscinas-praias flutuantes (anunciadas há um ano no “Diário de Lisboa”) vão ser estudadas por técnicos. Diário de Lisboa. Ano 48º nº 16371, 17/07/1968, p. 10-11.

A construção de uma esplanada entre Cascais e Monte Estoril. Diário Popular. Ano XXVI nº 9249, 17/07/1968, p. 10.

Piscinas flutuantes ao largo de praias portuguesas. Diário Popular. Ano XXVI nº 9249, 17/07/1968, p. 15.

Uma praia-piscina flutuante, invento português para utilidade turística. A Capital. Ano I nº 47, 17/07/1968, p. 5.

O Estoril vai ter uma piscina de mar? Publicação não identificada, 17/07/1968.

Piscinas desmontáveis concebidas por um artista português. Diário de Notícias. Ano 104º nº 36772, 20/07/1968, p. 7.

Esplanada à beira-mar do Monte Estoril a Cascais. Jornal da Costa do Sol. Ano V nº 222, 20/07/1968, p. 1.

Frente à Praia do Tamariz a primeira praia-piscina flutuante. A Capital. Ano III nº 846, 02/07/ 1970, p. 8.

Ao largo do Tamariz uma piscina-flutuante valoriza a cosmopolita zona balnear do Estoril. Diário de Lisboa. Ano 50º nº 17072, 02/07/1970, p. 8-9.

Novo tipo de piscina inaugurado amanhã no Estoril. Diário Popular. Ano XXVIII nº 9950, 02/07/1970, p. 23.

Uma piscina-flutuante é inaugurada amanhã ao largo da praia do Tamariz. O Século. Ano 90º nº 31683, 02/07/1970, p. 5.

Uma piscina flutuante ao largo do Tamariz. República. Ano 60 nº 14162, 02/07/1970) p. 8.

Uma piscina flutuante é hoje inaugurada na Praia do Estoril. Diário de Notícias. Ano 106º nº 37472, 03/07/1970, p. 7.

Uma piscina flutuante à disposição do público a partir de hoje em frente ao Tamariz. O Século. Ano 90º nº 31684, 03/07/1970, p. 5.

Uma piscina flutuante no mar (frente ao Tamariz) foi inaugurada pela Sociedade Estoril-Sol. Jornal da Costa do Sol. Ano VII nº 325, 11/07/1970, p. 5.

Seapool. The Anglo-Portuguese News. Nº 979, 11/07/1970, p. 5.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. A Capital. Ano IV nº 1211, 09/07/1971, p. 12.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário de Lisboa. Ano 51º nº 17437, 09/07/1971, p. 4.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário de Notícias. Ano 107º nº 37836, 09/07/1971, p. 19.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário Popular. Ano XXIX nº 10315, 09/07/1971, p. 8.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. O Século. Ano 91º nº 32049, 10/07/1971, p. 2.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário de Notícias. Ano 108º nº 38192, 06/07/1971, p. 2.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário Popular. Ano XXX nº 10671, 06/07/1971, p. 15.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. O Século. Ano 92º nº 32404, 06/07/1971, p. 2.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário de Lisboa. Ano 52º nº 17795 (8 de Julho, 1972) p. 12.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário de Notícias. Ano 108º nº 38194, 08/07/1972, p. 2.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. Diário Popular. Ano XXX nº 10673, 08/07/1972, p. 12.

Reabriu a Piscina Flutuante do Tamariz [anúncio]. O Século. 92º nº 32406, 08/07/1972, p. 2.

Other Sources

Patents

ANAHORY, Eduardo — Floating Artificial Beach. Australia: Intelectual Property Australia, 1970 [1968]. AU1968044066. Available at: https://ipsearch.ipaustralia.gov.au/patents/1968044066 [Consult. 06/06/2024].

ANAHORY, Eduardo — Módulo e Estrutura Flutuantes e Embarcação. 1979 [1978] BR7802383. Available at: .https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?DB=EPODOC&II=5&ND=3&adjacent=true&locale=en_EP&FT=D&date=19791127&CC=BR&NR=7802383A&KC=A [Consult. 06/06/2024].

SILVA, António Bustorff; BELO, Duarte; ANAHORY, Eduardo — Brevet d’Invention: Plage Artificielle Flottante. Paris: Ministère de L’Industrie, Service de Propriété Industrielle, 1968. FR1525436. Available at: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?DB=EPODOC&II=4&ND=3&adjacent=true&locale=en_EP&FT=D&date=19680517&CC=FR&NR=1525436A&KC=A [Consult. 06/06/2024].

Video recordings

Arquivos RTP — Praia Piscina Flutuante no Estoril. Lisbon: Rádio Televisão Portuguesa, 1970. 36s, p&b, mute. Available at: https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/praia-piscina-flutuante-no-estoril/ [Consult. 16/05/2024].

Arquivos RTP — Inauguração da Praia Piscina Flutuante no Estoril. Lisbon: Rádio Televisão Portuguesa, 1970. 3m 50s, p&b, mute. Available at: https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/inauguracao-da-praia-piscina-flutuante-no-estoril/ [Consult. 16/05/2024].

Notes

1. He has always been, and will always be, a citizen of the world, he will never fully tie himself to a corner or a school, nor even to a single form of expression.” Jorge Amado, on Eduardo Anahory (BORGES, 2010: 203).

2. The advance of the German army in Europe during World War II must naturally have had an impact on his stay in Brazil.

3. Anahory’s biographical and professional time line is adapted from BORGES, 2010.

4. Advertising slogan for the floating-beach-pool in the daily press in the summers of 1971 and 1972.

5. According to Graça Anahory Vasconcelos and Ana Tostões, in interviews conducted for this article by the author.

6. Anahory’s list of contacts is based on the names identified in BORGES, 2010, with the addition of the identification of people indirectly referred to there.

7. Aiola is the name of a typical Sesimbra artisanal fishing vessel which Anahory borrowed.

8. In addition to sharing the same birth year, Anahory and Athouguia both attended the architecture course at the Escolas de Belas Artes in Lisbon and Porto, and collaborated on the project for the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Athouguia even designed a “shack-like” vacation house for the Arrábida, next to Anahory’s, which he would never build (CORREIA, 2018: 299).

9. “The architect Pedro Cid, also present, only claimed authorship of the project with institutional bodies. Years later (after Eduardo Anahory’s death), his nephew José Anahory is said to have asked Cid about his involvement in the Porto Santo Hotel, to which Cid again stated that he had only signed the project, and that the work was entirely developed in Anahory’s studio.” (BORGES, 2010: 116)

10. BORGES, 2010, is preceded by TABORDA, 2007, in an article focussing solely on the Casa Aiola and the proposal for its restoration.

11. It is worth mentioning, as a curiosity, that it is in this issue of Domus, on the pages immediately following the article about the floating-beach-pool, that is published the article by Joseph Rykvert, Un omaggio a Eileen Gray pioniera del design, that would initiate the movement to rediscover Gray’s work.

12. Patent number 1.525.436 indicates three dates in its header, in the following order: “Filed on 9 May 1967, at 2:00 PM, in Paris. Issued by decree on 8 April 1968. (Official Bulletin of Industrial Property, no. 20, dated 17 May 1968.) (Patent application filed in Portugal on 9 May 1966, under no. 45.738, in the name of the applicants.)”

13. This was the Algarve Hotel in Praia da Rocha, Portimão, designed by Raul Tojal and inaugurated in 1967 (BORGES, 2010: 143).

14. A third patent was registered by Anahory in Brazil in 1978 and published in 1979.

15. Interestingly, the project was presented to the public in July 1968, therefore before the submission of this patent.

16. It is mentioned as a curiosity, but also as an expression of its social and cultural relevance, that a photograph of the Piscine Deligny appears on the cover of the June 2nd 1968 edition of Jornal de Notícias as an illustration of Paris’s return to normality after the previous month’s protests.

17. Ticiano Violante, artist, decorator, and model maker, was responsible for creating, among others, the model of the city of Lisbon before the 1755 earthquake, which is now displayed in the Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta.

18. The news appears in the article O Estoril vai ter uma piscina de mar? (Is Estoril Getting a Sea Pool?), a digital copy of which was kindly provided by Luiza Carrelhas Albuquerque (great-niece of Eduardo Anahory). Unfortunately, the source of the original publication could not be identified.

19. The equivalent, today, would be two hundred and forty thousand to three hundred and twenty thousand euros.

20. The texts published in the various newspapers present occasional variations, and even inaccuracies (planned instead of patented, granite instead of granulated, among others). The excerpt transcribed here is from the article Ao largo do Tamariz uma piscina-flutuante valoriza a cosmopolita zona balnear do Estoril [Offshore from Tamariz a floating-pool enhances the cosmopolitan bathing area of Estoril], from Diário de Lisboa, Ano 50º nº 17072 (2 July 1970) pp. 8-9.

21. The boat departed from the pier on the eastern side of the Tamariz beach, as shown in the RTP report of the official inauguration. Available at: <https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/inauguracao-da-praia-piscina-flutuante-no-estoril/>.

22. 50 escudos is equivalent to about 18 euros today.

23. Vemol was a company specialized in reinforced plastics, with which Anahory would later work again on the project for a removable seating area (BORGES, 2010: 160).

24. Available at: <https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/praia-piscina-flutuante-no-estoril/>.

25. As recounted by Ana Tostões, in an interview.

26. Édifice-événement ‘subi’ and édifice-événement programmé’, in the original. The literal translation of ‘subi’ is ‘suffered, but it was felt that ‘occurred’ better translates the author’s intention.