Pedro Castelo

pcaste01@mail.bbk.ac.uk; pedro@esap.pt

Birkbeck University of London, England e CEAA/ESAP, Porto, Portugal.

For citation CASTELO, Pedro – Receção e comentário sobre a cultura arquitetónica moderna brasileira em Portugal. Uma breve análise a partir de duas publicações periódicas de arquitetura. Estudo Prévio 23. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2023, p. 80-105. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/23.5

Received on 4 September 2023 and accepted for publication on 15 September 2023.

Creative Commons, licence CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Reception and Commentary on Brazilian Modern Architectural Culture in Portugal. A Brief Analysis from Two Periodicals on Architecture.

Abstract

This article focuses on the exchanges of modern architectural culture that took place from the mid-20th century onwards between South America, particularly Brazil, and Portugal. This brief analysis will be based on the elements that constituted the reception and dissemination of this same culture in various specialised publications, particularly through the periodicals that existed at the time. The aim is to reconstitute a path of relations between the two hemispheres that took place during a relatively recent period in the history of architecture, through a detailed survey of its key moments.

When analysed from the perspective of what has been published, these moments of cultural and artistic influence, because they are scarce but not irrelevant, become measurable and important for the historical review of the processes of contact between the two geographies. A thorough analysis can give us a more realistic perspective of the processes of knowledge production and transfer that took place during a period of intense development.

On the one hand, we intend to review the content of these relations between Portugal and Brazil in the field of architecture, and on the other establish a critical framework of how this relationship came to be understood within historical mythologies affected by phenomena of post-colonial collective psychology.

In this process we will observe the characteristics of these influences, not only from an aesthetic and creative point of view, with its various nuances, but also as an intellectual and ideological model of production and urban and social development, which, by crossing borders, became prevalent and hegemonic.

We will begin by briefly identifying the fundamental role of certain publications in the dissemination and international recognition of a bold modern architecture, alongside the productions of the great masters of the post-war modern movement, which was deemed as characteristically Brazilian. We will then consider how they were received in Portugal and reported on first by ARQUITECTURA magazine, and then by BINÁRIO magazine, where we will delve into the establishment of a more structured exchange between Portugal and Brazil, with more extensive and regular coverage by the latter. We will conclude with a comment on these processes and what they can mean for us today.

Keywords: Brazilian Architecture; Architectural Exchange; Cultural Dissemination; Post-War Era; Architectural Publications; Brazil-Portugal Relations; Urban and Social Development; Modernism; Periodicals Analysis; Cross-Cultural Influences; Cultural Identity; Historical Review.

A brief comment on the great flows of modernism.

One of the most established narratives of the avant-garde movements of the first half of the 20th century originates precisely from one of the century’s most remarkable occasions of movement and exchange. The migratory flows of the post-war period were notably identified by Siegfried Giedion in his book “Space, Time and Architecture” as having played a fundamental role in the development and maturation of modern architecture, in which the processes of hybridisation led to a diversification of languages and fostered the creation of new architectures.

The adoption and expansion of the canons of modern architecture during the first half of the 20th century, especially those stemming from the American exodus, were numerous and have been widely studied and identified; among them are the unavoidable contributions of figures such as Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, or Moholy-Nagy, Victor Gruen, among many others, who acted as educators and professionals in the USA, helping to revolutionise the teaching of architecture and shaping the course of 20th century architecture[1].

But they were far from the only ones who, as part of a wider diaspora, had the opportunity to put their ideas into practice in an equally unimpeded way. In Brazil, for example, we have the work of Warchavchik or the Bardi couple, who were able to translate the aspirations of a society that was beginning to industrialise, especially in the post-1930 period, helmed by Getúlio Vargas, incorporating different elements from their personal background and cultural heritage.

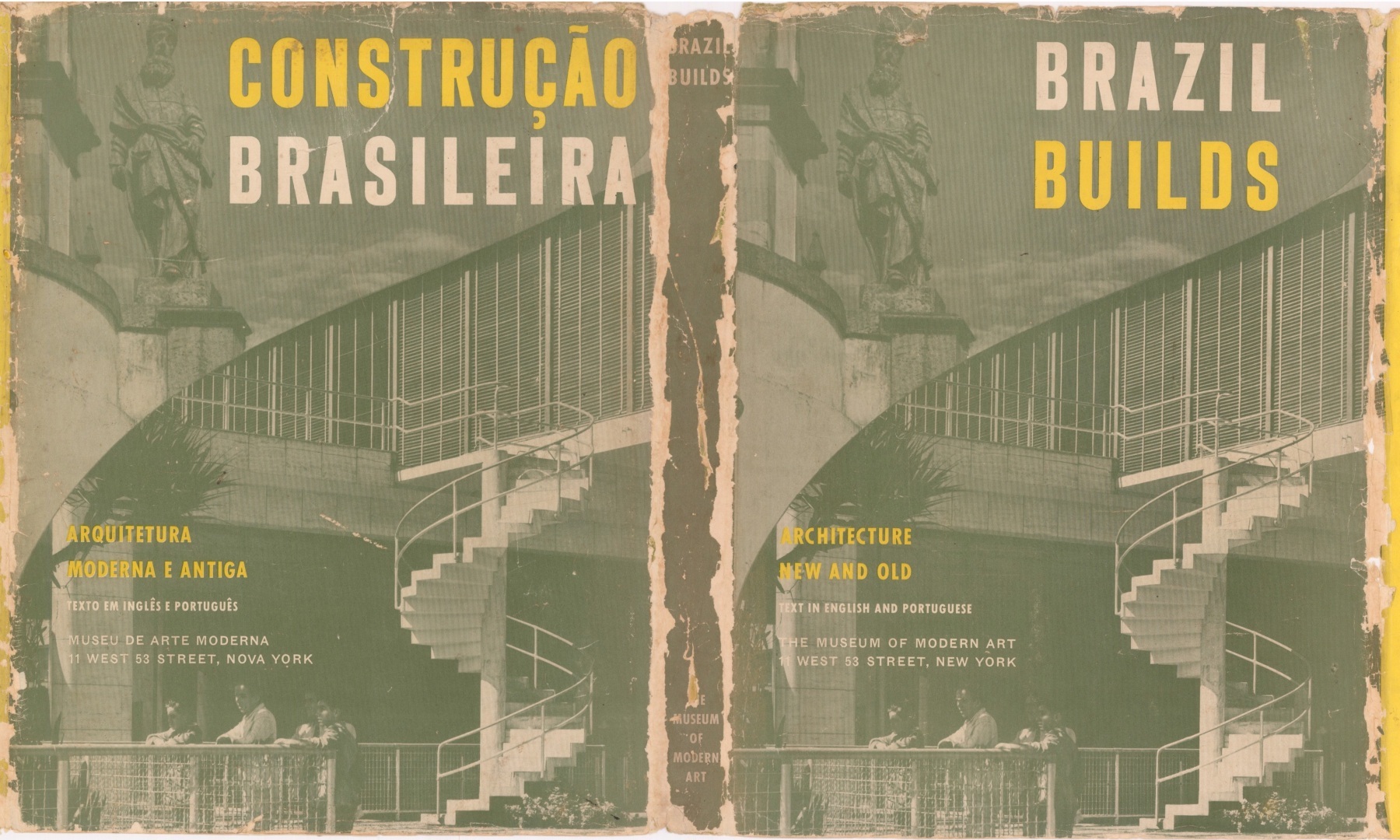

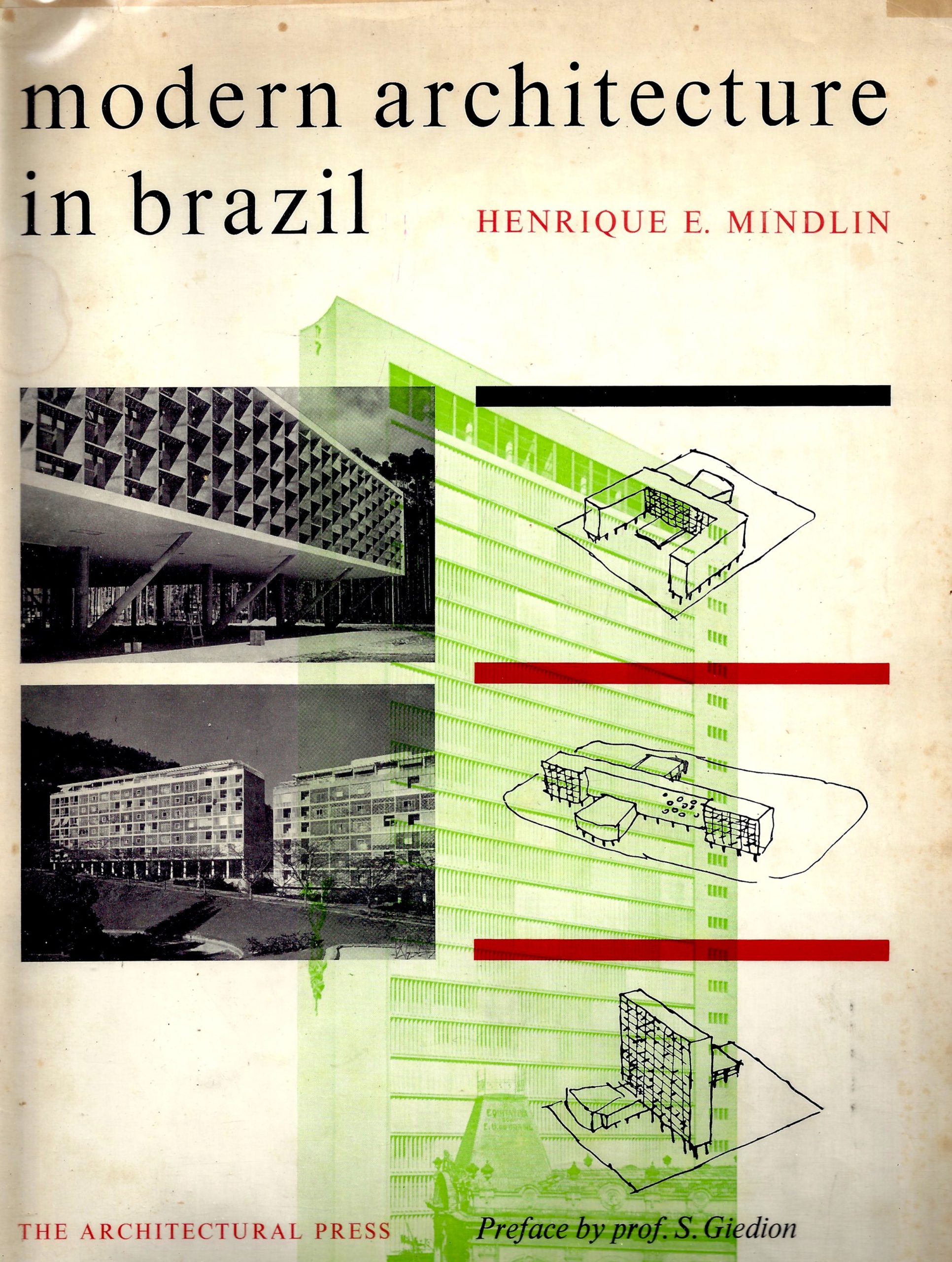

It is in a context of economic, social and artistic expansion that Brazil is asserting itself as a new centre of avant-garde creativity. But it is above all thanks to certain moments of dissemination that this identity is established and comes to be recognised on an international level. This effort to establish a common line of thought and a genealogy of creativity first appears in the exhibition of works and projects entitled “Brazil Builds”, which took place in 1943 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curated by Philip Goodwin, with photos by Kidder-Smith; whose catalogue, due to its dissemination effect and institutional recognition, became an ex-libris of Brazilian architecture (Figure 1). This was followed in the 1950s by Henrique Mindlin’s book Modern Architecture in Brazil, published in trilingual, which further promoted and strengthened Brazilian architecture internationally (Figura 2). And of course, the interest that followed in the publication of special issues in renowned magazines such as L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, Forum or The Architectural Review [2], which, by widely circulating the work and role of these architects, established them as unavoidable figures in the canon of the modern South American movement (Figures 3.1 to 3.6).

Figure 1 – Brazil builds: architecture new and old, 1652-1942. By Philip L. Goodwin, photographs by G. E. Kidder Smith. MoMA 1943.

Figure 2 – Modern architecture in Brazil. By Henrique E. Mindlin. 1st edition by Colibris, Rio de Janeiro, 1956. (below) L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui special editions, dedicated to Brasilien Modern Architecture.

Figures 3.1 to 3.6 – L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui nº 13/14 (September 1947); The Architectural Forum (November 1947); The Architectural Review (March 1944).

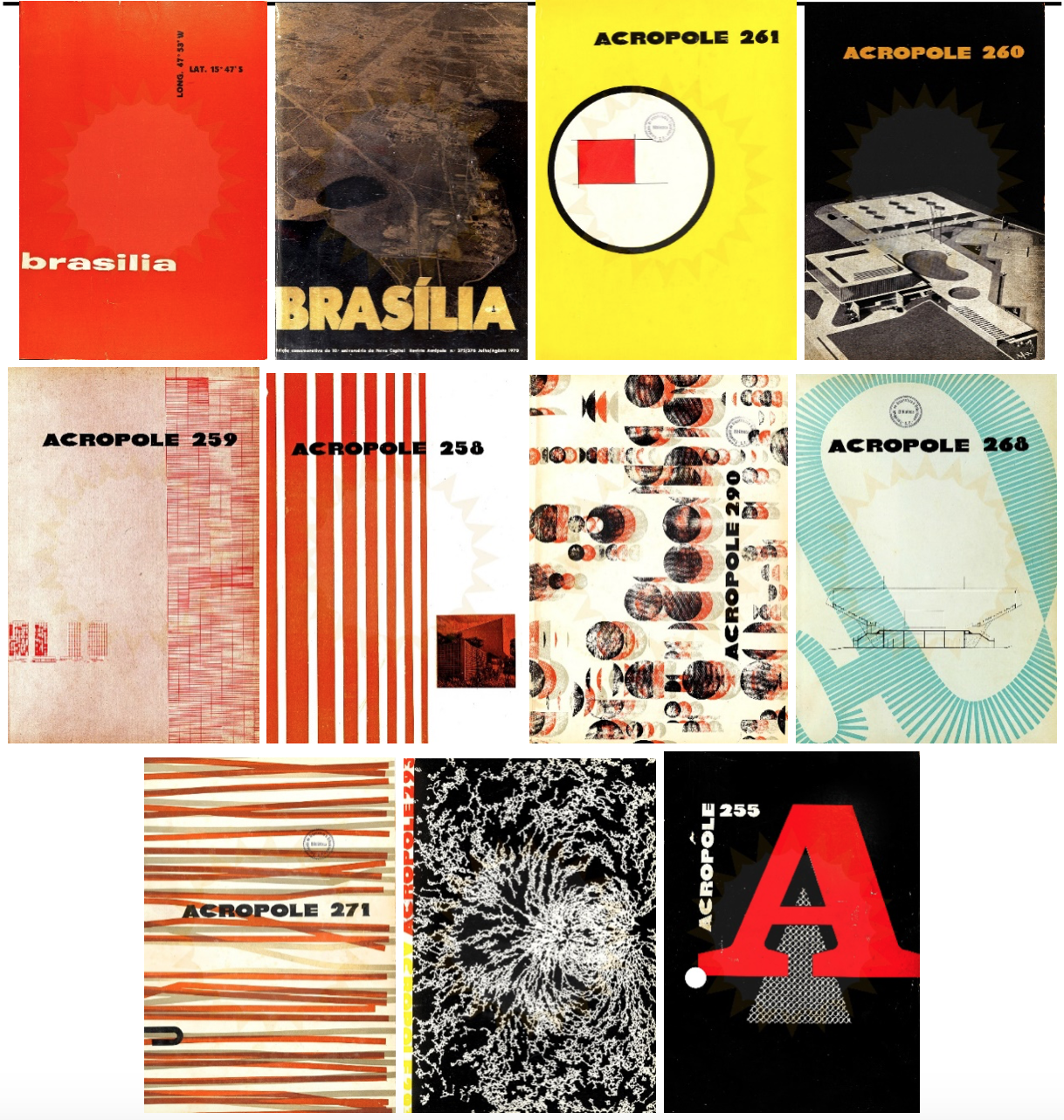

At the same time, the magazines that proliferated in Brazil and which also circulated in Europe and Portugal, played a fundamental role in the dissemination and sedimentation of Brazilian architectural culture, both nationally and internationally: among them was the magazine Acrópole (São Paulo), published from 1938 to 1971, which documented an important part of the history of urban development in the state of São Paulo. The magazine, founded by Roberto Corrêa Brito, was responsible, especially under Max Grunwald (from 1952), for publicising some of the most illustrative examples of Brazilian modernism and the works of authors as diverse as Siegbert Zanettini, Ruy Ohtake, Oswaldo Bratke and Rino Levi (Figures 4.1 to 4.11).

Figures 4.1 to 4.11 – Several numbers of the magazine Acrópole, including spetial numbers dedicated to Brasilia.

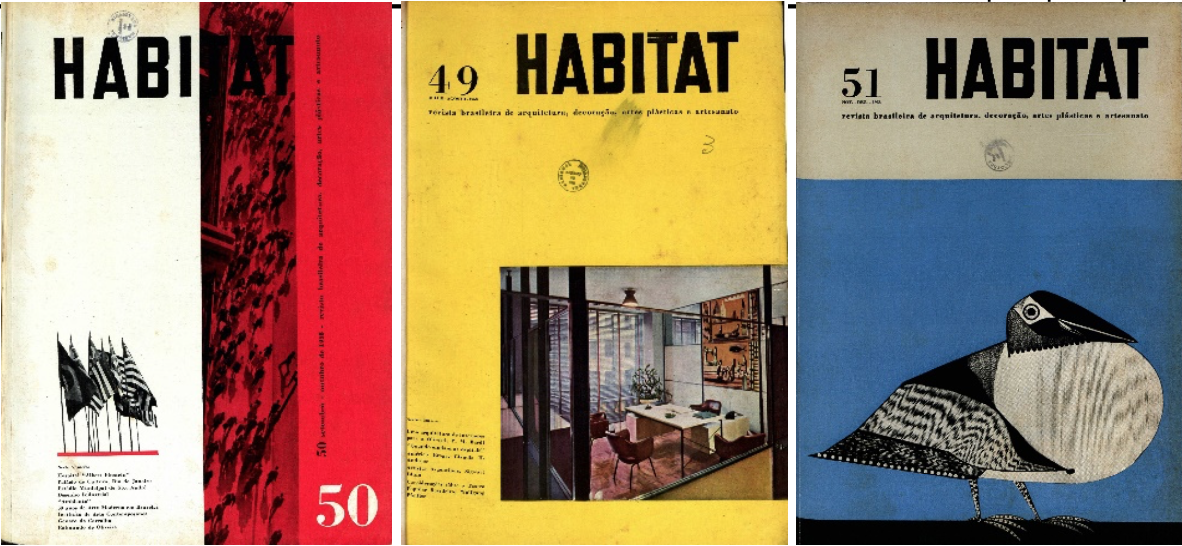

Habitat magazine, also from São Paulo, existed between 1950 and 1965, directed initially by Lina Bo and Pietro Bardi and later by Abelardo de Sousa and Geraldo Ferraz. It is usually under the direction of the former that it is studied, as it correspondes to the phase in which these protagonists used it as their favoured instrument for intellectual and artistic experimentation. During its early years, “Habitat” was the vehicle for their external and inquisitive gaze, capable of intersecting modernist ambitions with the local, historical and diverse cultural production of Brazil (Figures 5.1 to 5.3)[3].

Figures 5.1 to 5.3 – Several editions of Habitat.

Also important was the magazine Módulo, which began in March 1955 in Rio de Janeiro under the direction of architect Oscar Niemeyer and engineer Joaquim Cardozo, in collaboration with Rodrigo Melo Franco de Andrade, writer Rubem Braga and architect Zenon Lotufo (Figures 6.1 to 6.5). This magazine had a more troubled existence, namely due to its headquarters being invaded and looted by the military regime in 1965, leading to its interruption. However, the magazine reappeared later, returning to circulation between 1975 and 1989, but with different characteristics. As Heliana Angotti-Salgueiro states in her study of photographer Marcel Gautherot’s work for the magazine Módulo: in its first phase, the magazine’s editors and contributors saw modern architecture as “inseparable from the affirmation of national identity and culture, alongside not only the fine arts, but also historical heritage, vernacular architecture, aspects of the country’s nature, its folklore, popular art and other related themes.” (Angotti-Salgueiro: 11) Themes that will give more and more space to reports on the construction and architecture of Brasilia, which will become an increasingly dominant feature.

Figures 6.1 to 6.5 – Several editions of Módulo.

As a whole, these magazines had the role of stimulating architectural discourse and becoming a place where ideas crossed paths. The many articles and different reports on works, not only national ones, had the dual effect of broadening the repertoire of architectural solutions, with a globalising result, but also of solidifying the disciplinary contributions, giving them greater transformative power and a greater social dimension.

The reception of modern Brazilian architecture in Portugal, some key moments reported by the Portuguese magazine ARQUITECTURA.

One of the first important events in the dissemination of modern Brazilian architecture in Portugal is announced in the magazine ARQUITECTURA, 28 January 1949, which comments on the visit to Europe of a group of Brazilian students, accompanied by Professor Wladimir Alves de Sousa, and the respective conferences and exhibitions that took place at the Instituto Superior Técnico in Lisbon (Figures 7.1 and 7.2).

Figures 7.1 and 7.2 –Arquitectura n.º 28 (January 1949)

The following was written about the conference: “It was an event of unusual interest in the field of fine arts. Although Portuguese architects already had a clear understanding of the value of current architectural trends in Brazil, through various foreign publications, the subject gained new interest and greater objectivity when explained by someone who has experienced it up close.” (Arquitectura n.º 28: 26).

Regarding the exhibition, they add that it was extensive and emphasise the fact that it included not only models, photographs and drawings, but also “a collection of magazines and publications, placed in such a way as to allow easy consultation.” (Arquitectura n.º 28: 26). Once again confirming the importance of the printed document in this dissemination process.

The significance of this event is reaffirmed by the reactions it aroused, which can be seen in the immediately following issue (ARQUITECTURA 29, February and March 1949) in a letter from the Portuguese architect Formosinho Sanches, commenting on the exhibition and drawing a parallel with the Portuguese scene: “It is evident and natural that the Exhibition of Brazilian Architecture will have an impact on new spirits and, more importantly, on the architecture students of the two schools in the country. This reflection, he said, is natural and it’s good that we don’t let the spirit in which we all feel about renewing our architecture cool down.” (Figures 8.1 and 8.2) (Arquitectura n.º 29: 17).

Figures 8.1 and 8.2 –Arquitectura n.º 29 (February/March 1949)

This text shows how the exhibition led Portuguese architects to reflect on their own condition, producing certain expectations of progress. Formosinho Sanches expressed his desire to find a new, more avant-garde kind of architecture that could create a better society. In this sense, Sanches recognised this innovative and modern spirit in the examples coming from Brazil.

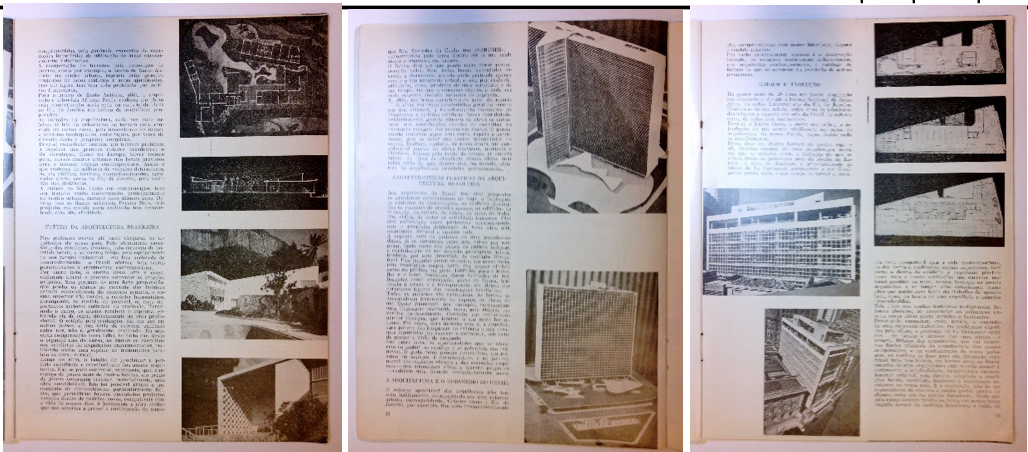

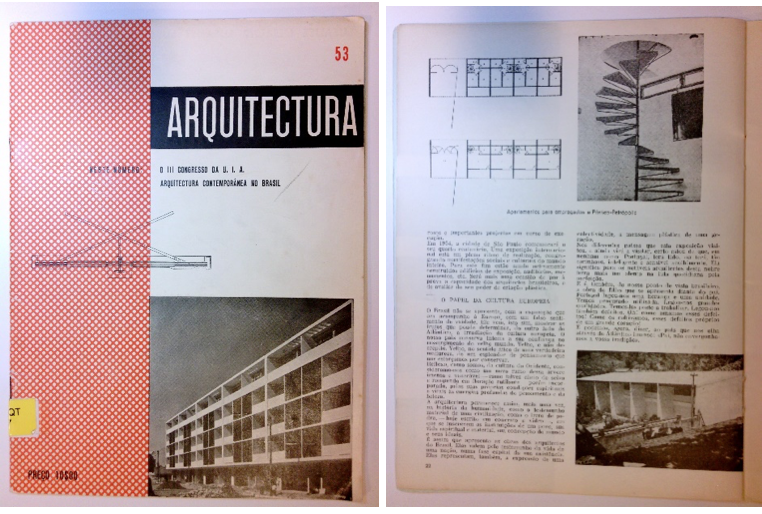

This exhibition was followed by a second one, also brought by Wladimir Alves de Sousa, on the occasion of the 3rd Congress of the International Union of Architects – UIA, held in Lisbon in September 1953, and published in issue 53 of ARQUITECTURA magazine in December 1954. Of the 600 participants from various countries, Brazil was the only representative from the American continent, which demonstrates its dynamism at international level and also its relevance to the context of Portuguese architects. This time, the exhibition was presented at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes in Lisbon and had an opening conference, during which many of the materials brought were widely publicised through an extensive publication of illustrations and comments in the magazine (Figures 9.1 to 9.7).

Figures 9.1 to 9.7 – Arquitectura n.º 53 (December 1954)

The quote presented in the communication states that “among the most notable manifestations of its material progress and artistic level, Brazil prides itself on having an architecture that is compatible with the needs of the present and its peculiar conditions of climate, soil and social demands” (Arquitectura n.º 53: 17). In addition, admiration is given to the “colour, texture, shape and volume” of the tropical vegetation that is present in the gardens created by Burle Marx, projects that were also highlighted in the exhibition.

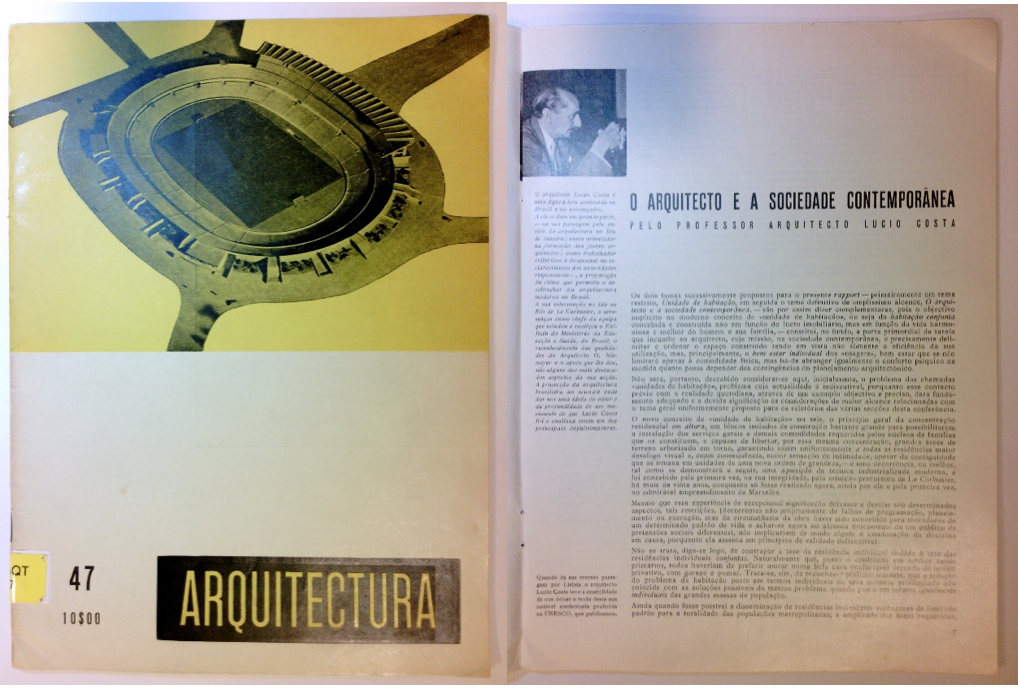

In parallel with the dissemination of built works, theoretical thinking also began to take shape and be publicised by the media. One of these moments in Brazilian architectural thought appeared a year before the second exhibition, by the hand of Lúcio Costa, in issue 47 of ARQUITECTURA magazine, in June 1953 (Figures 10.1 and 20.2).

Figures 10.1 and 10.2 – Arquitectura n.º 47 (June1953).

In the article, which was commissioned by UNESCO for a conference in Venice and entitled “The Architect and Contemporary Society,” Costa discusses the concept of the “housing unit”, as proposed by Le Corbusier and already experimented with in the Marseille block. In this and other essays, Costa strenuously defends the role of the architect as an active agent in the development of contemporary society, whose skill lies in the subtle balance between technical, sociological and aesthetic considerations to create housing solutions that meet a diversity of needs and constraints.

Lúcio Costa takes the opportunity to explore the limits of the discipline of architecture by defining the various factors that make it up: the historical context, the physical and social environment, the techniques and materials available, and the project’s objectives. In the text, Costa argues that innovations in modern construction allowed for greater freedom in the creation of architectural projects, merging previously irreconcilable concepts and opening up new possibilities for artistic expression in architecture. He concludes that the evolution of architecture is part of a broader process of social and economic change.

It’s interesting to note that, among Lúcio Costa’s texts, this is one of the ones that ends up being published in Portugal; a text in which, in addition to disciplinary principles, a more universal architecture is affirmed. Lúcio Costa emerges as one of the main theoreticians of the Modern Movement, deviating from his other texts in which he tries to structure a path of modernity with a more national character and reconciliation with local and historical traditions, such as in “O Aleijadinho e a Arquitectura Tradicional” (1929), “Razões para uma Nova Arquitectura” (1934), and “Documentação Necessária” (1937). These were texts that, in retrospect, could have had more resonance among Portuguese architects, especially those of the younger generations.

It is in this choice between a more universal architecture and a more regional one that an apparent divergence emerges in the development of the architectural cultures of Brazil and Portugal. However, this divergence is actually illusory, manifesting itself simultaneously in multiple dimensions and different geographies, including Brazil and Portugal. For example, in Portugal, even in a context of deep inequalities and widespread poverty, there were also pressures from late industrialisation and the impacts of accelerated globalisation that translated into architectural expressions outside the regionalist canon [4].

Discussions about the preservation of historical heritage, the right to housing and issues linked to new technologies – such as prefabrication, new topologies, new programmes, new architectural forms and different ways of building the city – were frequent. These themes were part of a set of contrasting political and aesthetic options.

In Brazil, all these concerns were also debated, as documented in the magazine BINÁRIO from the moment it began to be published. Curiously, from that moment on, ARQUITECTURA magazine, until its last issue in 1989, showed little interest in architectural developments in Brazil. This prolonged absence of Brazilian architecture coincides with the moment when Portuguese architecture began a process of re-evaluation of modern architecture, driven largely by debates often associated with the CIAM congresses and materialised by the third series of the magazine ARQUITECTURA.

One possible interpretation is that the editors of ARQUITECTURA, from the middle of the century onwards, focused their efforts on the search for their own specific architectural identity, in which Brazil’s large-scale modern architectural culture and international influence had no place.

The notable exception to this trend of disinterest was the magazine BINÁRIO. While ARQUITECTURA relegated Brazil to the background, BINÁRIO emerged as a platform that continued to publicise what was being produced in Brazil. This editorial duality reflects not only different orientations within the Portuguese architectural community, but also the complex cultural and professional exchange between the two countries [5].

The magazine BINÁRIO: Brasilia

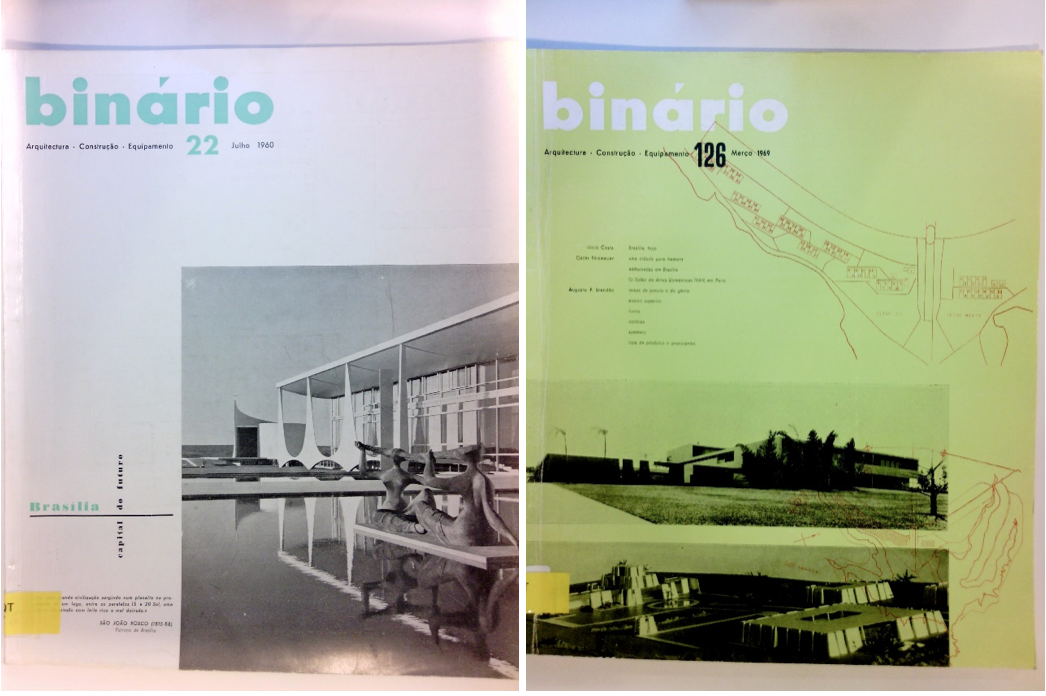

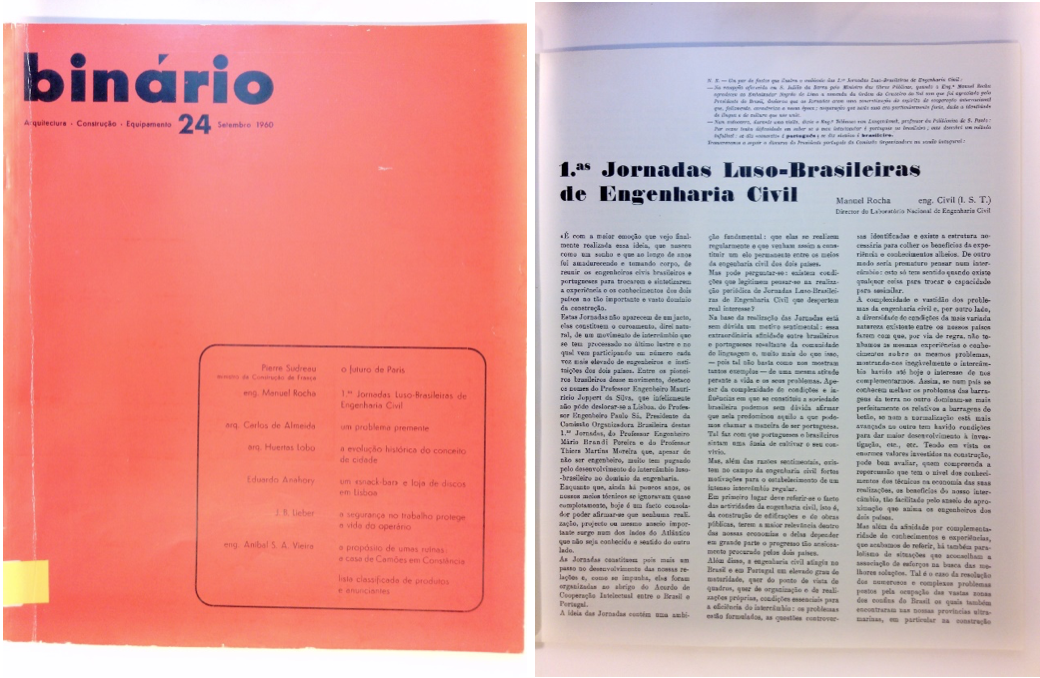

In Portugal, the magazine BINÁRIO (1958/1977), due to its more internationalist slant and the fact that its editorial project was more based on reproducing articles from foreign periodicals, emerged as the specialised magazine that, since the late 1950s, has offered more extensive coverage of architectural production and urban development in Brazil, including through the establishment of exchange partnerships such as the Jornadas Luso-Brasileiras de Engenharia Civil.

As we have seen in the large-circulation magazines mentioned above, some editions of BINÁRIO are dedicated entirely to Brazilian architecture, more specifically to Brasilia (Figures 11.1 and 11.2). The issues BINÁRIO 22 (July 1960) and BINÁRIO 126 (March 1969) report extensively on the major constructions of the new capital and once again include texts by Lúcio Costa and Niemeyer, respectively.

Figures 11.1 and 11.2 – Binário n.º 22 (July 1960) and Binário n.º 126 (March 1969).

It’s also important to note here that the editors’ interest was not restricted to Brasilia alone; other important urban interventions were also highlighted in BINÁRIO magazine, such as the Copacabana coastal arrangement in issue 92 (May 1966), Lúcio Costa’s plan for Barra da Tijuca in issue 135 (December 1969), among others.

With regard to the paradigmatic case of Brasilia, it is pertinent to explore its significance and analyse the material from the time more closely. It was in this first special issue on Brasilia that another of Lúcio Costa’s important texts appeared, this time on art and architecture and the need to educate the masses in this area. In the text, called “A arte e a educação” (Art and education), Lúcio Costa mainly addresses the relationship between art and society in the industrial age (Figure 12).

Figure 12 – “A arte e a educação”, by Lúcio Costa. Binário n.º 22 (July 1960).

For Costa, although the industrial revolution introduced new ways of recording, reproducing and disseminating art, it also destabilised the old social order, creating a diverse public with varying levels of understanding and appreciation of art. Costa suggests that the problem of the arts is above all an economic-social problem and that the solution depends on resolving this fundamental issue.

It is in this sense that he emphasises the importance of educating the masses in the various artistic areas, a vision aligned with the broader political project of creating a welfare state. A project that for a few decades was able to mitigate the inequalities that had prevailed until then through processes of access to basic goods such as education and health, which guaranteed a modicum of social movement.

Lúcio Costa saw this project as the natural process of development resulting from the industrial revolution, where the role of architecture and the architect in society would be crucial.

Although his vision could be considered elitist, as the architect took a prominent position in it, and despite believing that, in the first phase of industrial massification, there would be an inevitable devaluation of art, its accessibility to the masses was a fundamental step towards the egalitarian elevation of society as a whole and the logical conclusion of the process begun by the industrial revolution.

Also part of the same progressive vision is Niemeyer’s short text on Brasilia “A City for Men” published in BINÁRIO 126 (March 1969), in which he complains about the lack of effort to finish and humanise it (Figure 13). Niemeyer writes:

“It is also clear that we would like to feel it humanised, but this in the exact sense of the word, giving all its inhabitants, without class discrimination, the same possibilities for a happy life.” … “Unfortunately, this is not the meaning they give to the term ‘humanise’, … But it is useful that they talk about humanising the new Capital, because it allows us to correct a mistake, calling them to join the progressive movements that fight poverty, privilege and lack of education, with a view to the better society they seem to desire. On that day, Brasilia will be the humane and welcoming city that Lúcio Costa foresaw.” (NIEMEYER, 1969: 474)

Seen from a historical and contemporary perspective, it is interesting to note that both Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer seemed, through their texts, even with all their social idealism, to be more interested in the end of the work as a finite and perfect artistic object than in an architecture/process of open and indefinite development. A contradiction that is also evident in the publication itself when, in the same issue in which they concern themselves with the favelas of Brasilia, we see extensive publication of embassy projects with all their associated representativeness.

Figure 13 – “Uma Cidade para Homens”, Binário n. º 126 (March 1969).

The texts by Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer offer a complex and sometimes contradictory vision of what Brasilia could and should be. They reflect the tensions between art and society, the ideal and the real, the closed work and the continuous process, tensions that still spark debate and reflection today. This is how BINÁRIO brings us the critical vision of two of its most important protagonists, through which we can reconsider the architectural and social projects and utopias that defined an era.

The magazine BINÁRIO: The ‘Jornadas’ (conferences) of Luso-Brazilian Civil Engineering and the role of editor Anibal Vieira

It is due to the force of expansion and development represented by Brasilia that this gravitational pull towards Brazil is largely generated and which led to the creation of the first Luso-Brazilian civil engineering conferences under the Intellectual Cooperation Agreement between Brazil and Portugal. This initiative was accompanied by an economic cooperation agreement and had the support of the respective Presidents of the Republic, involving different government ministries (in the case of Portugal, the Ministries of Culture and Overseas Territories), as well as the awarding of commendations and study visits [7] (Figura 14).

Figure 14 – “Declaração sobre Cooperação Económica entre Portugal e o Brasil”, Binário n.º 112 (January 1968).

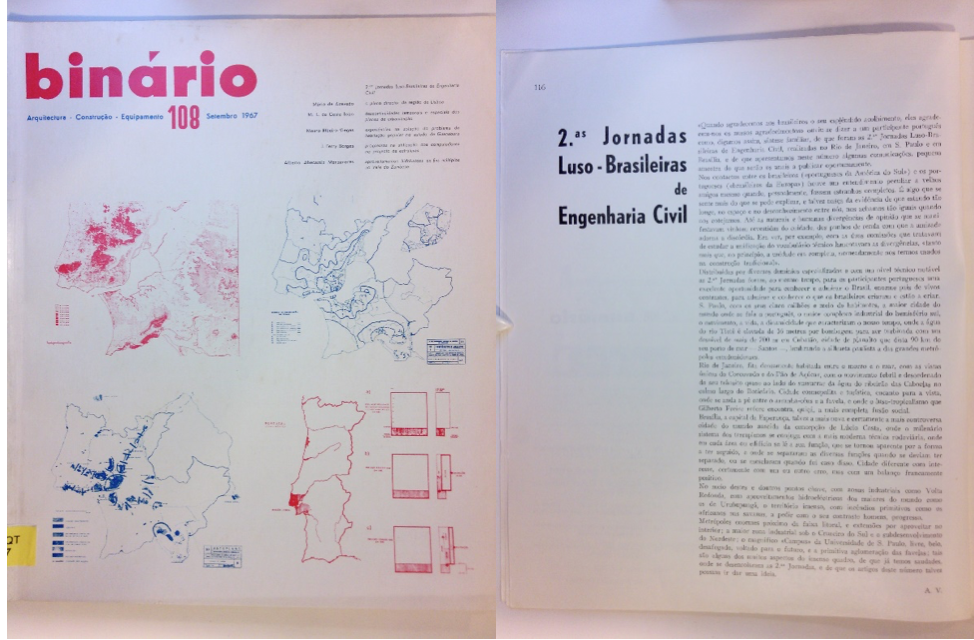

This exchange led to regular collaboration between the promoters of these events and the specialised press, with various articles and presentations being exchanged and published in different magazines. Starting in the Portuguese case with the publication in BINÁRIO 24 (September 1960) of the text of the inaugural session of the conference, signed by Engineer Manuel Rocha, at the time the director of LNEC – Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil Português (Figures 15.1 and 15.2). And later, with the second conferences, which took place in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Brasília, presented together with some of the presentations by Brazilian colleagues, namely by Engineer Mauro Ribeiro Viegas, professor at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, in issue 108 of BINÁRIO magazine (September 1967) (VIEGAS, 1967:136-140) (Figures 16.1 to 16.4).

Figures 15.1 and 15.2 – Binário n.º 24 (September 1960).

Numerous debates were held on a wide variety of topics, including: Major Infrastructures (dams, ports, roads, etc.); Housing; Building Structures; Integrated City or Regional Development Plans; and Education and Research. The published analyses reveal increasingly complex and well-founded understandings of these themes, including notions of a more time-extended urbanism, which thanks to the experience of building Brasilia, whose frustrations expressed by Lucio Costa and Niemeyer, set out above, were beginning to be investigated and/or adopted.

Figures 16.1 to 16.4 –Binário n.º 108 (September 1967) and Binário n.º 112 (January 1968).

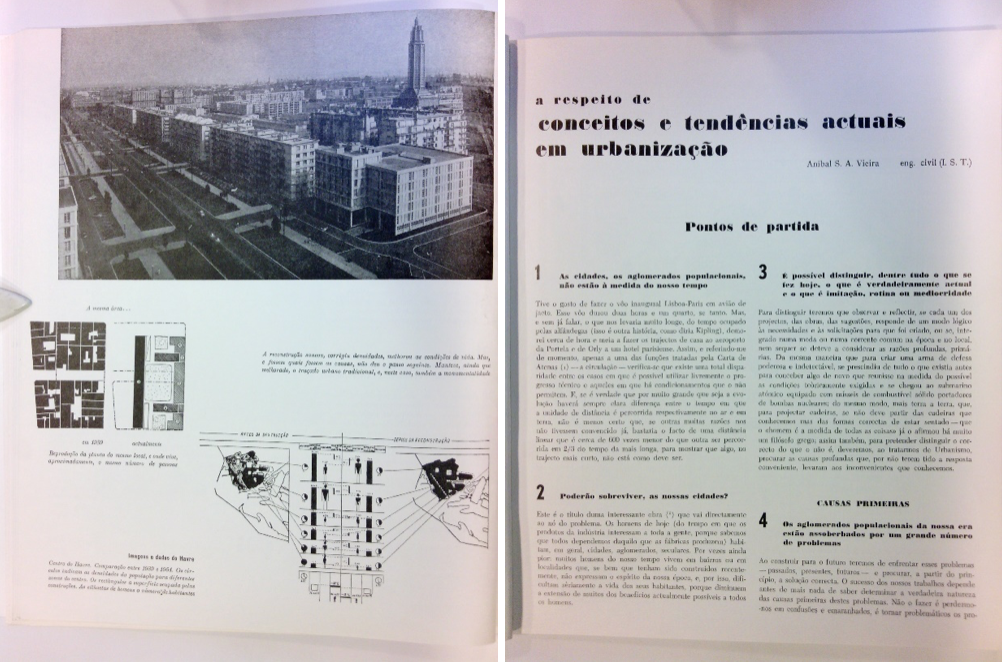

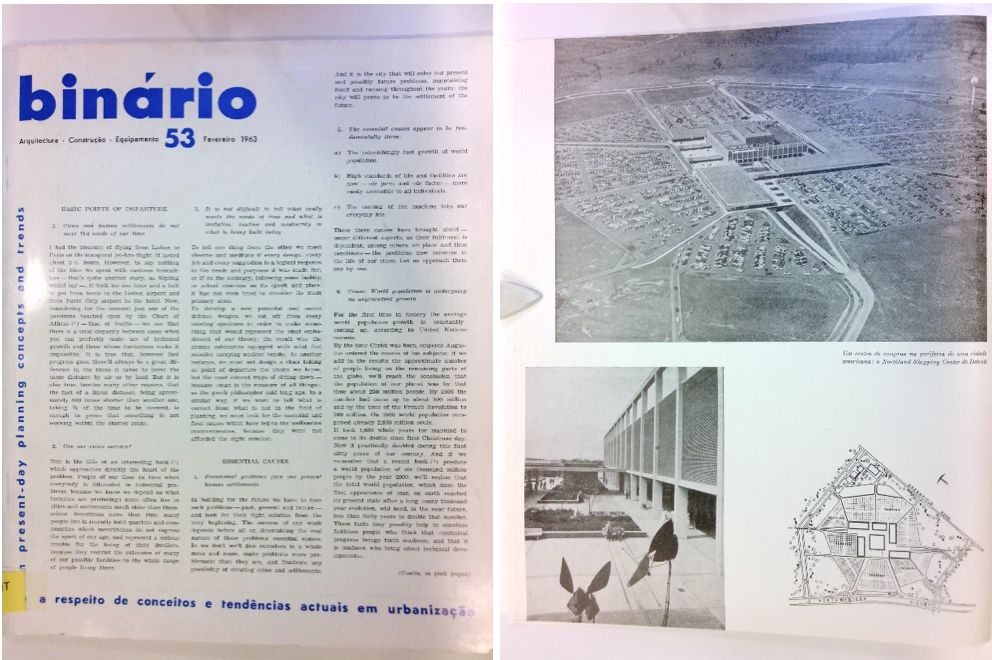

Further proof of this theoretical deepening was the study carried out by the editor of BINÁRIO magazine, and one of the main driving forces behind the conferences, engineer Aníbal Vieira, in the special issue BINÁRIO 53 (February 1963). The result of several trips by Vieira, including to Brazil, where he presented 98 “current concepts and trends in urbanisation.” (Figures 17.1 to 17.4)

Figures 17.1 to 17.4 – Binário n.º 53 (February 1963).

This special issue sparked a dialogue, later published in BINÁRIO 69 (June 1964), with a text by architectural engineer Carlos Lodi[8], first published in ENGENHARIA magazine in São Paulo (LODI, 1963: 504 – 505), in which he summarises Aníbal Vieira’s study and compares it with the urban development of the city of São Paulo[9]. This dialogue continues with other texts by Lodi[10], but also by other Brazilian and Portuguese authors, largely from the conferences, but also from other meetings where, among more technical subjects[11], the problems of urbanism were discussed in the light of technological progress, as well as the physical and social shortcomings arising from that same progress.

This exchange continued to be gradually strengthened, including with the participation of Aníbal Vieira in the planning of Nova Iguaçu (reported in BINÁRIO 141, June 1970); or with the Ouro Preto Municipal Plan by the Portuguese architect Alfredo Viana de Lima (announced in BINÁRIO 152, May 1971). And also in texts that, for example, are increasingly critical of modernist proposals in general and Brasilia in particular[12].

At least for as long as BINÁRIO was published (the magazine ceased publication in 1977), this exchange seems to have existed, largely thanks to the efforts and interest of editor Aníbal Vieira. However, it arose in a context in which, despite the openness brought about by the end of the Portuguese dictatorship in 1974, architecture ended up becoming increasingly closed off within its own disciplinary field. This phenomenon makes the discipline more insular and self-referential, something that is clearly reflected in the specialised magazines.

It is therefore not surprising to find observations such as those expressed by Tânia Beisi Ramos and Madalena Cunha Matos in their article “Reception of Brazilian Modern Architecture in Portugal – Records and a Reading”. According to them, from the mid-1970s onwards, there was ‘a slow withdrawal, [resulting in] an invisibility of contemporary Brazilian architecture’ (p. 17) on the part of Portuguese architects.

In fact, the end of the 1970’s brought radical changes not only to Portuguese society, but also to the entire world. These were years marked by an economic crisis, geopolitical realignments resulting from the end of the Cold War, the rise of neoliberalism and individualistic culture – strongly promoted by Thatcher and Reagan – and the omnipresence of the personal computer, among other significant transformations. At the same time, there was also a paradigm shift in architecture itself. These changes altered the nature of the moments of exchange, which continued to exist, even though they became increasingly punctual[13].

The profound changes in architectural culture in Portugal and Brazil during the second half of the 20th century have led to an increase in awareness and historicisation of the most important moments in architectural development in both countries. The study by Beisi Ramos and Cunha Matos is an example of this. This aspect contributes to mutual recognition of the importance of better understanding the dialogue and coexistence of modern architecture in each country and in their respective transatlantic relationship. It is at this crossroads that, through new surveys, research and publications, we can continue to deepen the unique contributions and occasional overlaps between these two contexts and the global panorama of architectural production.

In short, the architectural and urban planning dialogue between Brazil and Portugal, as documented in the magazines ARQUITECTURA and BINÁRIO until the end of the 1980s, reveals the coexistence of different intellectual and political perspectives in both countries. While ARQUITECTURA was known for focusing on an approach that emphasised an architectural identity of a more regional and social nature, BINÁRIO presented a more neutral and international vision, where there was room for the dissemination of Brazilian architecture. This editorial dualism not only illustrates the different orientations within Portugal’s architectural community, but also reflects the complexities of cultural and professional exchange between Brazil and Portugal.

Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer’s vision of Brasília, published in BINÁRIO, offers us a mirror through which to assess the inherent tensions between theory and practice, the ideal and the real, the global and the local. Their work and thought remain a valuable heritage for future generations of architects, urban planners and theorists, reminding us of the ambiguities and challenges that characterise architectural and urban planning practice.

The Jornadas Luso-Brasileiras de Engenharia Civil and editor Aníbal Vieira’s contribution to BINÁRIO magazine reinforce the crucial role of platforms for dialogue and collaboration in shaping contemporary architecture and urbanism. These initiatives have not only fostered theoretical and practical development in both nations, but have also served to strengthen cultural and intellectual ties between Brazil and Portugal.

At the heart of this exchange is the ongoing question of how the different modernities present in these two hemispheres were full of nuance and complexity, a question that, given the current environmental urgencies and socio-political challenges, remains relevant and unresolved. This is undoubtedly the most lasting legacy of these publications and discussions: a reminder that the search for solutions in architecture and urbanism is an ongoing process of negotiation between diverse forces, perspectives and contexts.

Bibliography

III Congresso da União Internacional dos Arquitetos – UIA, e Exposição de Arquitectura Contemporânea Brasileira. Arquitectura, Lisboa, n. º53, dezembro 1954, p. 9-22.A Visita dos Estudantes Brasileiros de Arquitectura. Arquitectura, Lisboa, nº28, janeiro 1949. Secção comentários, p. 26.

ANGOTTI-SALGUEIRO, Heliana – Marcel Gautherot na revista Módulo – ensaios fotográficos, imagens do Brasil: da cultura material e imaterial à arquitetura. Ed. Anais do Museu Paulista. São Paulo. N. Sér. v. 22. n.º1, jan.- jun. 2014, p. 11-79.

Binário, Lisboa, n.º 22, julho de 1960 (número especial dedicado a Brasília).

Binário, Lisboa, n.º 53, fevereiro 1963 (número especial dedicado ao tema: conceitos e tendências atuais em urbanização)

Binário, Lisboa, n.º 126, março de 1969. (número especial dedicado a Brasília)

COSTA, Lúcio; O Arquiteto e a Sociedade Contemporânea. Arquitectura, Lisboa, n. º47, junho 1953, p. 7-10, 19.

COSTA, Lúcio; A arte e a educação. Binário, Lisboa, n.º 22, julho de 1960, p. 223-224.

DOMINGOS, Nuno; PERALTA, Elsa – Cidade e Império. Dinâmicas Coloniais e Reconfigurações Pós-Coloniais. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2013.

FERREIRA, Raúl Hestnes – Algumas Reflexões sobre a Cidade Americana. ARQUITETURA 91, janeiro/fevereiro de 1966, p.1-8.

FERREIRA, Raúl Hestnes – Aspectos e Tendências Actuais da Arquitectura Americana. ARQUITECTURA 98, julho/agosto de 1967, p.148-155.

GOODWIN, Philip L. – Brazil builds: architecture new and old, 1652-1942. MoMA 1943.

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, n.º 13-14, setembro de 1947 (número especial dedicado à arquitetura brasileira).

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, n.º 42-43, agosto de 1952 (número especial dedicado à arquitetura brasileira).

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, n.º 90, junho de 1960 (número especial dedicado à arquitetura brasileira).

LODI, Carlos – A respeito de conceitos e tendências atuais em urbanização. Revista do Instituto de Engenharia. São Paulo, ano XXI, v. XXI, n.º 248, nov-dez./1963, p. 504-505.

MINDLIN, Henrique E. – Modern architecture in Brazil. 1st edition by Colibris, Rio de Janeiro, 1956.

NIEMEYER, Oscar – Uma Cidade para Homens. Binário, Lisboa, n.º 126, março de 1969, p. 474.

NOGUEIRA, Franco; MAGALHÃES, Juracy de – Declaração sobre Cooperação Económica entre Portugal e o Brasil. Binário, Lisboa, n.º 112, janeiro 1968, p. 41.

RAMOS, Tânia Beisi; MATOS, Madalena Cunha – Recepção da Arquitetura Moderna Brasileira em Portugal – Registos e uma Leitura. Docomomo Brasil, 2016.

ROCHA, Manuel – 1ª Jornadas Luso-Brasileiras de Engenharia Civil. Binário. Lisboa, n.º 24, setembro de 1960, p. 295-296.

SANCHES, Formosinho; Arquitectura Moderna Brasileira, Arquitectura Moderna Portuguesa. Arquitectura. Lisboa, n.º 29, fevereiro e março de 1949. Secção cartas de leitores, p. 17.

STAHL, Frances – Forças de Formação da Arquitetura Americana Contemporânea. Binário, n.º 37 e 38, outubro e novembro 1961.

STUCHI, Fabiana Terenzi – Revista Habitat: um olhar moderno sobre os anos 50 em São Paulo. São Paulo: Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo de São Paulo, 2007.

The Architectural Forum, novembro 1947 (número especial dedicado à arquitetura brasileira).

The Architectural Review, março 1944 (número especial dedicado à arquitetura brasileira).

VIEIRA, Aníbal – 2ª Jornadas Luso-Brasileiras de Engenharia-Civil. Binário. Lisboa, n.º 112, janeiro 1968, p. 116-135.

VIEGAS, Mauro Ribeiro – Experiências na solução do problema da habitação popular no Estado da Guanabara. Binário. Lisboa, n.º 108, setembro 1967.

Notes

-

In Portugal, this story comes to us through the magazine BINÁRIO, issues 37 and 38 (October and November 1961, respectively), told in an extensive article written by Frances Stahl, entitled “Formative Forces of Contemporary American Architecture,” in which she describes precisely the various contributions that were part of this exodus. In her article, Stahl identifies a linear historical continuum in a list of architects whose architectural vocabulary was being developed in America. Among the profiles published in the article are the architects: Richard Neutra, Mies Van Der Rohe, Victor Gruen, Edward Stone, Eero Saarinen, Minoru Yamasaki, I.M. Pei, and, in the second part, Paul Rudolph and Victor Lundy. Another in-depth study that demonstrated the influence of US architecture was the essay by Raul Hestnes Ferreira, published in two parts in ARQUITECTURA 91, January/February 1966, and ARQUITECTURA 98, July/August 1967. The first part was entitled “Some Reflections on the American City”, and the second “Current Aspects and Trends in American Architecture”, respectively. Like Stahl, Hestnes established a historical comparison of the different paths taken by American architects in relation to European ones, while evaluating the unique contributions of the most prominent architects. In America, he spoke of Wright, with his individual designs and organic expression, as well as his own approach to traditional American culture; he wrote about Sullivan and his classical, functional vision of the city; about Mies, whose practice, in his opinion, did not evolve beyond the refinement of his own repertoire. Whereas in Europe, he said, the processes of architectural renewal were accelerated by Le Corbusier’s capacity for reinvention, or thanks to the contributions of the C.I.A.M. group, among others.

-

Issues of L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui dedicated to Brazilian architecture: n.º 13-14, September 1947; n.º 42-43, August 1952; and n.º 90, June 1960. From the Forum magazine, we have the issue of November 1947, and from Architectural Review, the issue of March 1944.

-

STUCHI, Fabiana Terenzi – Revista Habitat: um olhar moderno sobre os anos 50 em São Paulo. São Paulo: Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo de São Paulo, 2007.

-

In the midst of stark inequalities and widespread poverty, Portugal underwent a significant shift between the late 1950s and the mid-1970s. The country’s rapid economic growth was fueled by delayed industrialisation, setting the stage for subsequent economic aspirations and architectural developments. This dual nature of the era was vividly reflected in the pages of ARQUITECTURA, which captured the architectural and urban evolution of the country against the backdrop of its broader social changes. The magazine not only detailed the tangible manifestations of Portugal’s economic ambitions, as seen in its infrastructural and service developments, but also served as a vessel for more abstract discussions on design philosophies, education, social aspirations, and critiques that the country’s architects were grappling with.

-

As Miguel Cardina explains in the book “O Século XX Português” (The Portuguese 20th Century, 2020), there is also the phenomenon related to countries with a colonial past, which stems from historical wounds that causes recurring cases of either amnesia or prejudiced disinterest in the colonised country within the colonising country. With rare exceptions, throughout the lifespan of the magazine ARQUITECTURA – one of the few major specialised magazines in Portugal – there is a noticeable absence of articles on Brazilian architecture, just as there is a strange absence of articles on architecture for and in the Portuguese colonies, which were still under Portuguese administration in the mid-20th century. This neglect, of which ARQUITECTURA was undoubtedly a part, is also described in the book “Cidade e Império. Dinâmicas Coloniais e Reconfigurações Pós-Coloniais” (City and Empire: Colonial Dynamics and Post-Colonial Reconfigurations) by Nuno Domingos and Elsa Peralta (Edições 70, 2013).

-

This Agreement was later followed by a declaration on economic cooperation between Portugal and Brazil, signed by Franco Nogueira (Foreign Minister of Portugal) and Juracy de Magalhães (Minister of Foreign Affairs of Brazil) in Lisbon on September 7, 1966 (see BINÁRIO 112, January 1968, page 41). This agreement aimed to facilitate the implementation of Luso-Brazilian business partnerships or the establishment of business opportunities between both countries, specifically for the exploration of mining resources and related activities. Further agreements were established between LNEC (Portugal) and the universities of Rio de Janeiro and Brasília, leading to the exchange of engineering professors, as demonstrated by the report still published in BINÁRIO 112, page 45, about the lectures given by Brazilian professor Anderson Moreira da Rocha at LNEC.

-

Ambassador Negrão de Lima conferred the Order of the Southern Cross, awarded by the President of Brazil to Engineer Manuel Rocha. The first meetings that took place in Lisbon were followed by a study visit to the North of the country, sponsored by the Hydro-Electric companies of Zêzere, Cávado, and Douro. Among the Brazilian participants, the following individuals are mentioned: Eng. Telémaco van Langendonck (Professor at the Polytechnic of São Paulo); Professor Engineer Maurício Joppert da Silva (who could not be in Lisbon); Professor Engineer Paulo Sá (Chairman of the Brazilian Organizing Committee); Professor Engineer Mário Brandi Pereira; and Professor Thiers Martins Moreira.

-

Carlos Lodi was an engineer and urban architect. He served as the president of the Brazilian Federation of Housing and Urbanism, director of the Department of Urban Planning for the São Paulo City Hall, and was an honorary member of the Town Planning Institute of London.

-

The points raised related to: i) the need for planning São Paulo according to regional development plans; ii) the issue of São Paulo still not adopting an open planning regime; iii) the necessity of providing São Paulo with more perimeter avenues near the city center (in accordance with the new linear and non-concentric model, as opposed to the typical development of central areas); iv) the urgency of promoting a renewal of the processes and bodies involved in São Paulo’s urban planning. (LODI, Carlos – BINÁRIO 69, June 1964, p. 375).

-

For example, Lodi contributed to issue number 85 of BINÁRIO (October 1965) with a text for the second Luso-Brazilian conferences, which had meanwhile been cancelled. The text was titled ‘The Need for Regional Expansion and Permanent Organisation in the Planning of Large Cities’ (p. 994-997).

-

For example, Aníbal Vieira writes in BINÁRIO 176 (May 1973) a very interesting article on how Brazil managed to control a period of enormous inflation (1961-1971) with extremely agile monetary control and correction measures. These included the flexibility of exchange rates, temporary price adjustments, and, most importantly, wage adjustments, which helped a large portion of the population face interest rates that reached 100% annually in 1964, measures that would be unthinkable today given the neoliberal heterodoxy of the market.

-

For example, Dieter Hannemann writes in BINÁRIO 194 (November 1974) the article “Brasília – Fascist Architecture?”. In it, he criticises Niemeyer for sacrificing human scale by designing too many axes of symmetry and opting for monumentality, even drawing a parallel with the architecture of the Third Reich. The criticism also includes the observation that, in many of these projects, form doesn’t even follow function, a point corroborated by Niemeyer himself in one of his interviews published in BINÁRIO 208 (May 1976), where he states, ‘We deliberately contradict principles if that’s where our imagination leads us.

-

Among the notable examples of this interaction, the period of exile of Portuguese architect Conceição Silva in Brazil stands out. His work was the subject of a retrospective in ARQUITECTURA magazine issue 150, in July/August 1983 (4th series). More recently, projects like the Museum of Coaches in Lisbon, designed by Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha, and the Iberê Camargo Museum in Porto Alegre, by Álvaro Siza, highlight this bilateral connection. Also noteworthy, and potentially controversial, is the enrichment of the collection of the Casa da Arquitectura in Matosinhos with works by Brazilian architects, which culminated in the exhibition “Infinito Vão – 90 Years of Brazilian Architecture” in 2019.