Olga Konyukova

olga.konyukova@gmail.com

Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, PhD student in Contemporary Architecture. Country of Origin: Russia

To cite this article: KONYUKOVA, Olga – The Landscape of Time. Estudo Prévio 27. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, dezembro 2025, p. 73-95. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Disponível em: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/27.4

Received on July 16, 2025, and accepted for publication on October 20, 2025.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The Landscape of Time

Abstract

This article takes Hotel Podgorica (1967) as its point of departure to examine how a single building engages landscape not as neutral setting but as an active field of relations. Designed by Svetlana Kana Radević, a central figure in Yugoslav and Montenegrin architecture, the project emerged in a postwar moment and is read as a vehicle for imagining a new city and a new country at once.

The argument turns on the question of context, understood not only as the immediate site but as the wider urban and national landscape. Through a reading of the hotel’s spatial organisation, form and materiality, and its negotiation between city, river and topography, the article suggests that architecture can begin to inhabit landscape rather than merely overlook it. In this perspective, the relationship between landscape and architecture becomes a way of rethinking “nature” as an active participant, and Radević’s work appears as a critical instance of what would later to be called critical regionalism.

Keywords: landscape, time, ethic, memory, nature, culture.

I. Introduction – Landscape, Time, and the Ethical Position of Architecture

Figure 1 – Hotel Podgorica, Podgorica, Montenegro (1964–1967) (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Situated on the slope above the Morača River, Hotel Podgorica has become almost indistinguishable from its surroundings. Its rough concrete walls, studded with smooth river pebbles, seem to grow out of the terrain. Built between 1964 and 1967, the hotel was designed by Svetlana Kana Radević (1937–2000), arguably the most prominent Montenegrin architect of the socialist period. Born in Cetinje, the former royal capital of Montenegro, she moved to Podgorica for high school and later studied architecture in Belgrade (KATS, 2020). Marked by the wartime destruction of her homeland, Radević —whose work is often associated with Montenegrin regional modernism — searched for ways of aligning modern design with the nature and culture of her country, producing forms that are both contemporary and place-bound. In Hotel Podgorica, form follows not function in the conventional modernist sense, but the landscape itself — a landscape that gathers and registers the time of the country. As the building traces the curves of the river, it produces a sense of insistent presence in the here and now. In this way, Radević articulates a vision of the country’s past and future being constructed — quite literally — through concrete walls.

The full complexity of landscape and nature has been largely lost in modern discourse, where nature is reduced to scenery and landscape to image. Yet the word “landscape” itself reflects a deeper entanglement of shaping and meaning. Derived from the Dutch landschap, it originally referred not to a tabula rasa, but to terrain already worked by human hands. The suffix “-scape,” like “-ship,” implies active formation and relationality (HARTSHORNE, 1939, p. 149–151). Over time, however, the term shifted away from process toward appearance, not only in Germanic languages but also in Romance ones (paysage, paesaggio, paisagem) and Slavic ones (e.g. предео in Serbian and Montenegrin). Landscape came to be conceived primarily as something to be seen rather than as an active participant in shaping experience.

Landscape, however, is never neutral. As W. J. T. Mitchell argues, it is not a passive setting but a visual medium – an ideological construction that carries the weight of memory, power and projection (MITCHELL, 1994). Scalbert pushes further, challenging the visual paradigm altogether: for him, nature is not an image or mere context but a witness, a moral presence before which architecture must answer (SCALBERT, 2018). Taken together, these positions describe landscape as both image and ground, representation and material presence, symbolic construct and ecological condition. To build is to shape a landscape in time: how it is seen, remembered, inhabited and claimed.

Time, too, has often been treated as a neutral measure – external, linear, progressive. Latour disrupts this model by proposing a temporality that is relational, situated and materially embedded (LATOUR, 1993). Time, in this view, is not a container for events but a product of interactions between people, materials and environments. Buildings, like landscapes, do not merely exist in time; they participate in its making.

This essay explores how Hotel Podgorica holds these tensions – between nature and construction, image and matter, landscape and time. To speak of this building is to speak not only of form but of an ethical position. It raises a question: how might architecture respond to place? What does it mean to build not upon, but with, the land?

II. The Landscape of Architecture

Hotel Podgorica was designed in the early 1960s, after Radević won a national competition. She was still in her twenties when the building was completed in 1967. In a later interview with Pobjeda, she recalled her first impressions of the city: “I remember Titograd in ruins. I thought that was how a city was supposed to look” (RADEVIĆ, 1967).

Located along a bend of the Morača, at the fractured edge of a city still recovering from wartime destruction, the hotel occupies a site in which the very notion of “urban context” had become unstable. With little coherent built fabric around it, the project found its reference in the terrain — in the slope of the riverbank and the silhouette of the surrounding mountains.

Figure 2 – River Morača, view from Blažo Jovanović Bridge toward Hotel Podgorica (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 3 – Riverbank view toward Hotel Podgorica from the opposite side of the river (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

The Morača (Figures 2 and 3) — swift, uneven, edged by limestone cliffs and strewn with boulders — is not just a scenic feature; it is the project’s medium. The river carves gorges and gravel beds, producing both physical structure and symbolic register. Radević’s architecture does not treat this as background. It engages the river as a force, a logic to follow, absorbing the landscape rather than merely occupying it.

The building does not rise above the terrain, nor does it disappear into it. It moves along the slope, bends with the river, and draws its material from the ground it occupies. Architecture and landscape appear less as separate conditions than as parts of the same gesture — a continuous adjustment in which walls, paths and terraces follow the grain of the site. In this blurred zone, the boundary between built and unbuilt is no longer a line but a thickness, a shared territory in which the hotel gradually emerges from, and returns to, the landscape around it.

Figure 4 – Hotel view toward the Ribnica Fortress and the Morača River (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 5 – View toward Hotel Podgorica from the Ribnica Fortress (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

The position of the hotel is not neutral. Situated across from the historic core, it faces both river and city, suspended between centre and edge, “nature” and history. Following the competition proposal, the building was moved closer to the bridge, onto a steeper slope — an adjustment that introduced spatial dynamism and opened direct views onto the river (ALIHODŽIĆ, 2015, p. 33). More significantly, it established a deliberate visual dialogue with the ruins of the fifteenth-century Ribnica Fortress on the opposite bank (Figures 4 and 5). Orientation here is more than a response to topography; it expresses a value: that architectural form should acknowledge and extend the city’s historical continuity.

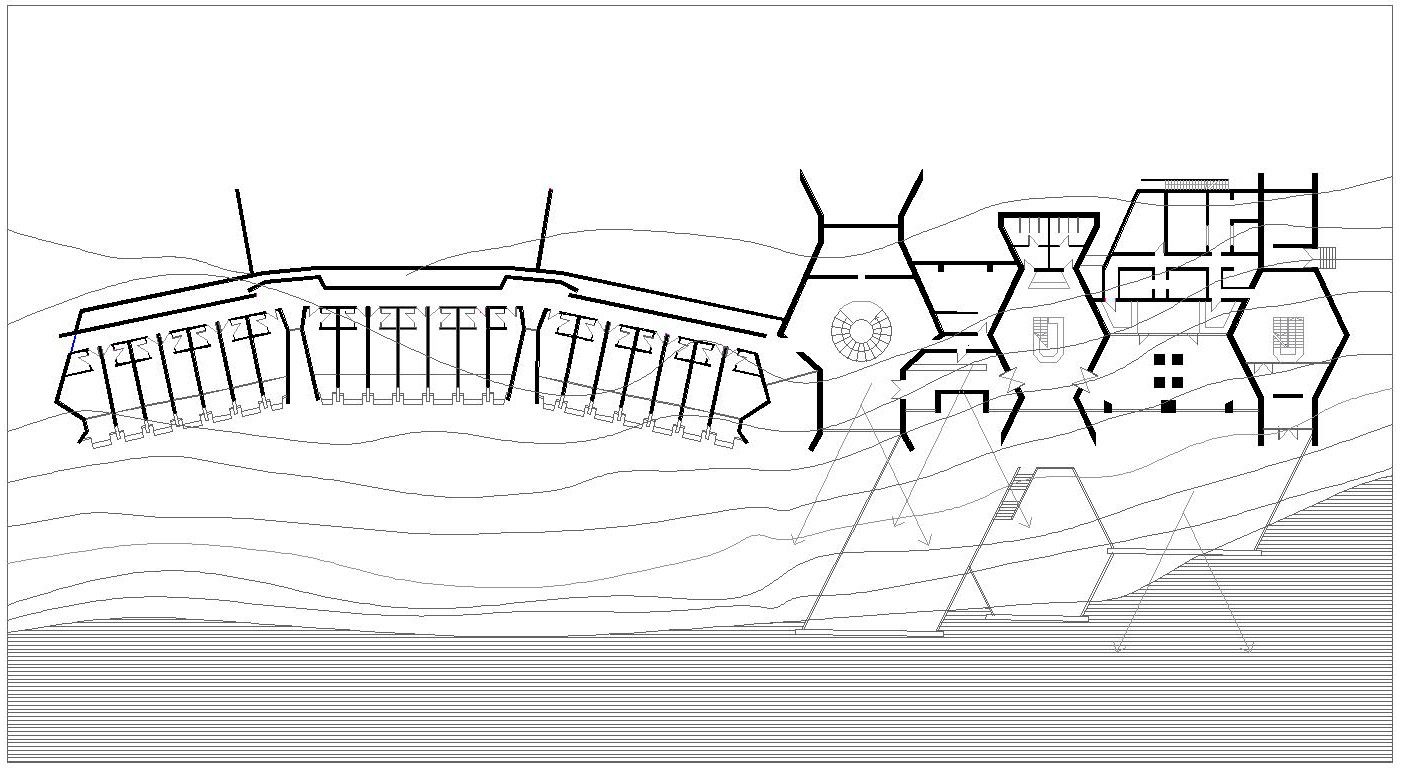

Figure 6 – Plan diagram of Hotel Podgorica (based on Radević’s drawings).

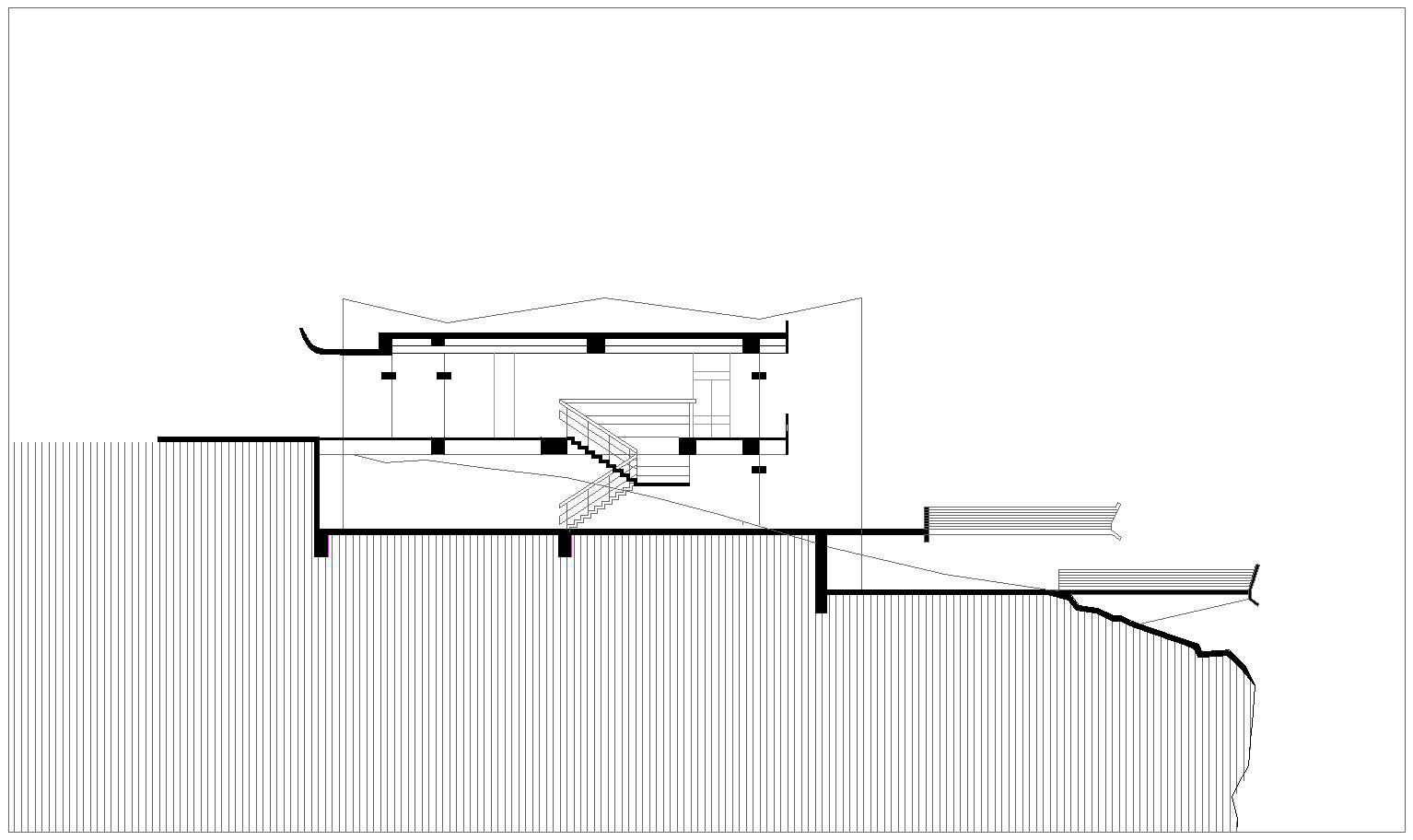

Figure 7 – Section diagram through the entrance and terraces (based on Radević’s drawings).

Figure 8 – View from a hotel room toward the Morača River (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 9 – View from a hotel room balcony toward the Morača River (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

The plan is asymmetrical, elongated (Figure 6). It tracks the river’s curve, stepping down the slope in staggered volumes. There is no single axis and no dominant entrance; mass is dispersed rather than concentrated. Circulation unfolds through a sequence of thresholds rather than a single grand gesture (Figure 7). Each room is held between thick wall-plates that frame a particular view, establishing an individual relationship with the river (Figures 8 and 9). Slopes dissolve into terraces, balconies into ledges. This stepping resists the monumentality of a fixed figure and produces instead a grounded temporality — an architecture experienced not as a moment of arrival but as a gradual descent.

Figure 10 – View from the hotel terraces toward the Morača River (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 11 – Natural river terraces along the Morača (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

The communal spaces perform a similar mediation. Lounges, terraces and dining rooms fan outward along the slope, opening toward the river at shifting angles (Figures 4 and 10). Reminiscent of the Morača’s layered banks, the river-facing lobbies unfold as a spatial sequence (Figures 7, 10). Their organisation follows the logic of the river—fluid, responsive, without strict hierarchy (Figure 11). These spaces do not prescribe movement; they accommodate it, creating time for looking, for tracing the water’s surface, for registering the presence of history and dwelling in the company of the river.

Figure 12 – Hotel Podgorica following the contours of the Morača River. (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 13 – Contours of the Morača riverbank (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

This conversation with the landscape continues through the building’s form. Nowhere is it more evident than in the curvature of the walls, which closely follows the outline of the riverbank. The edges of the hotel do not impose a new geometry on the site; they echo the river’s natural bends, translating its rhythm into architectural form (Figures 12–13). The structure does not abstract the landscape; it absorbs it, tracing the gentle inflections of the shoreline in concrete and stone. The hotel reads less as an object placed in the landscape than as a continuation of its flow, shaped by the same forces of erosion, gravity and time.

Figure 14 – Architectural elements of Hotel Podgorica. (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 15 – Natural elements of the Morača riverbank (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

The architectural elements themselves unsettle the conventional hierarchy of the building. Walls, glazing, windows, balconies and railings are treated not as subordinate components but as equal participants, organised less by an abstract structural order than by the movement of the river. Radević fragments the mass into a sequence of volumes, articulated through deep recesses, projecting balconies and thick concrete planes (Figure 14). These elements do not align in a rigid composition; they shift, stagger and break apart, echoing the irregular rhythm of the riverbank (Figure 15). In doing so, the architecture blurs the usual division between vertical supports and horizontal slabs. Load-bearing and enclosing elements slide into one another; structure and expression are no longer easily separated. The result is not a stable frame but a constructed flow—architecture that appears to move, lean and settle with the terrain.

Figure 16 – River pebbles embedded in the façade of Hotel Podgorica (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 17 – Surface texture of the concrete façade at Hotel Podgorica. (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 18 – River pebbles from the Morača(Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

The materiality of the hotel is perhaps its most radical feature. Its concrete walls are embedded with pebbles taken directly from the Morača (Figures 16–18). Each stone bears a distinct fracture; together they form a coarse, granular surface that resists the smoothness of conventional concrete. This is not metaphorical ornament, but a direct material continuity between building and site: the river is held within the walls, not symbolically but indexically. The surface is sedimented, differentiated by the breaks in each stone; it refuses monolithicity.

The building thus performs what might be called a temporal materiality—matter as layered time. The stones establish a continuous link between the hotel, the river, the ruins of Ribnica and Stara Varoš, the vernacular core on the opposite bank. This gesture resonates with a broader regional tradition of material embeddedness and topographic responsiveness (STAMATOVIĆ VUČKOVIĆ, 2024, p. 15–25). Radević uses local stone not merely as cladding but as structural logic, grounding the architecture in both geological and cultural terrain. The dark aggregate recalls the textures of the riverbed; the irregular surfaces absorb light, touch and weather, giving the building a presence understood less as fixed form than as slow endurance.

Landscape is no longer a passive setting but an active network of entangled agencies (LATOUR, 1993). Buildings are not objects imposed on the land, but participants in shared ecological and historical processes. Hotel Podgorica offers a concrete example of how architectural decisions can critically engage with their environment. Radević challenges the abstract, smooth logic often associated with modernism, replacing it with a rationalised natural form—expressed through siting, spatial organisation, elemental hierarchy and material continuity. The building is not an autonomous object but a temporal construct, shaped by, and shaping, natural rhythms.

Radević’s architecture folds, erodes and leans—towards river, terrain and time. It does not depict nature from a distance; it joins in its ongoing formation. In doing so, it unsettles a prevailing architectural logic in which nature is subordinated to functional rationality. Through its siting, form, structure and material, Hotel Podgorica appears not as an object in the landscape but as a continuation of it. In that continuity, it reorients architectural tactics, proposing a model of building grounded not in control or human dominance, but in attentive relation to what is already there: river, water, ground, stones.

III. The landscape of Titograd

To understand the cultural and spatial position of Hotel Podgorica, we must return to the landscape of the city itself. In the years following the Second World War, Podgorica was renamed Titograd, in honour of Josip Broz Tito, and designated the capital of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro. The renaming was not merely symbolic; it signalled a profound transformation of urban identity, overwriting the memory of the old town and embedding the city in a narrative of socialist rebirth. Titograd became not only a political centre, but a testing ground for the architectural and ideological ambitions of postwar Yugoslavia.

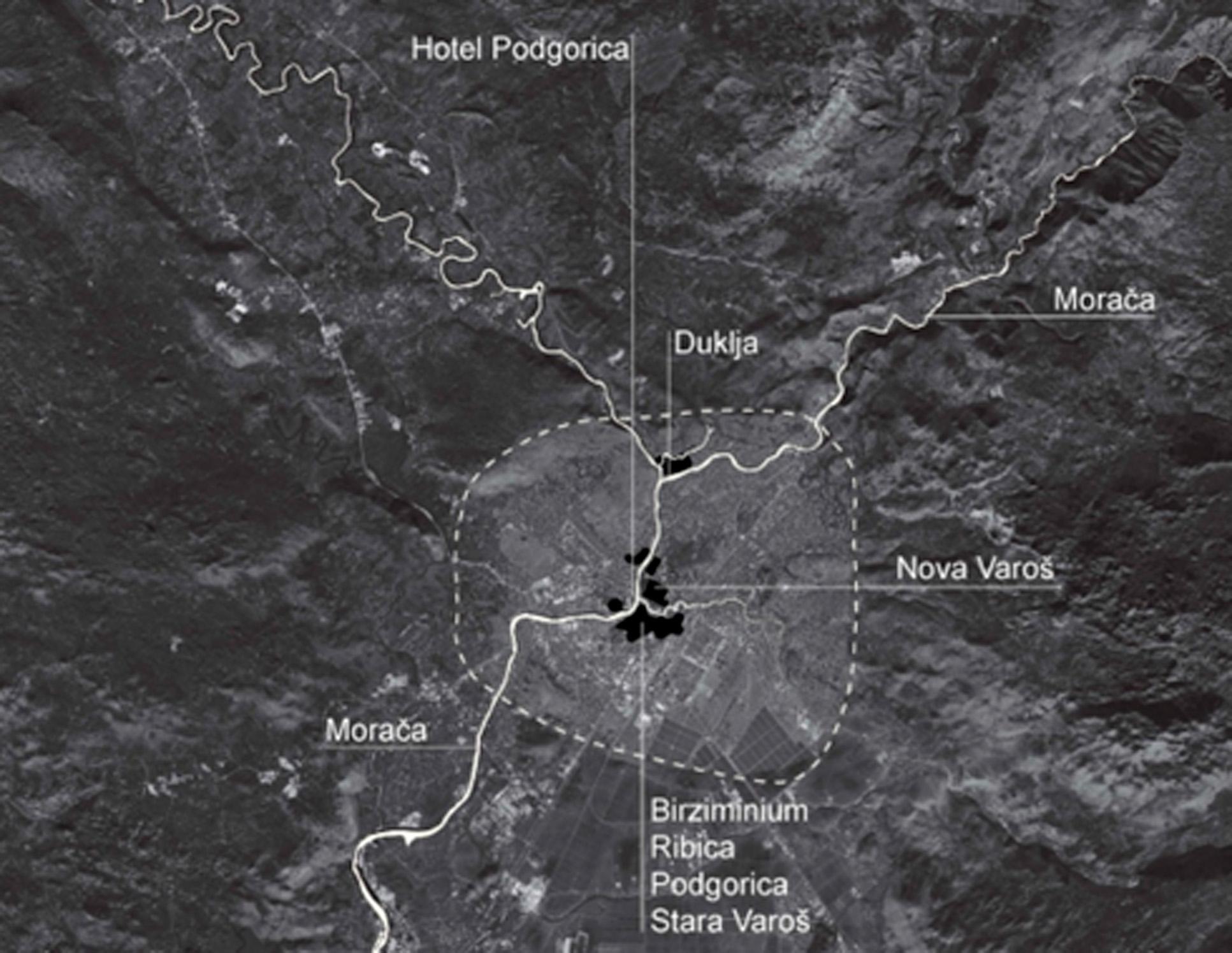

Figure 19 – The development of the region around the Moraca (based on PEROVIĆ, 2019: 7).

Set in central Montenegro, on the northern edge of the Zeta Plain, Podgorica is shaped by a wide expanse of flatland, multiple rivers and distant mountain ranges that form a dramatic backdrop and give the country its name. The Morača and Ribnica cut through the urban fabric, dividing the city into zones and structuring its geography (Figure 19). Much of Podgorica is organised along a rational grid, echoing the flat geometry of the plain. Near the rivers, however, this regularity breaks down: the terrain becomes uneven, the morphology more irregular. The grid gives way to fragments—narrow passages, sudden slopes, and the labyrinthine texture of Stara Varoš.

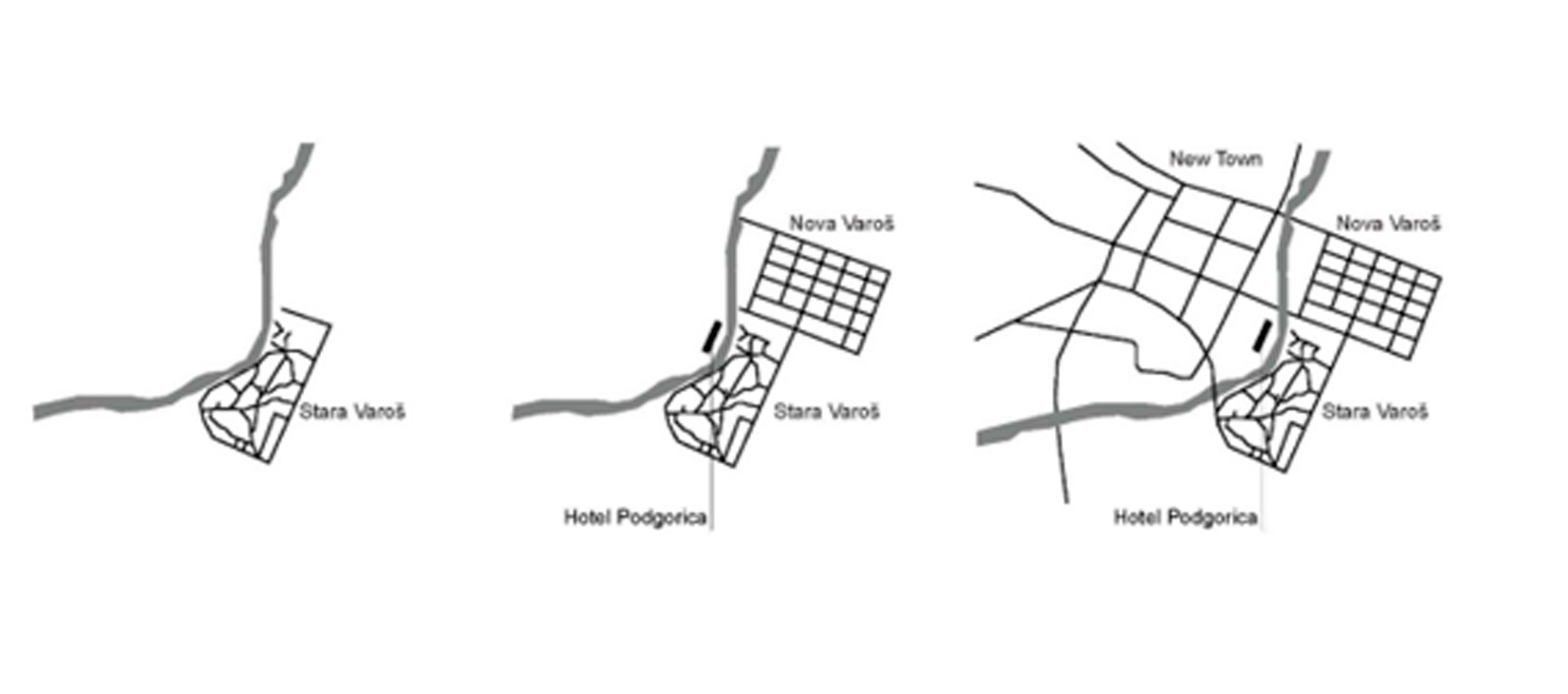

Figure 20 – Key phases in the development of Podgorica (based on ZEJNILOVIĆ, 2019: 56).

Historically, the city’s natural and topographic features have significantly influenced urban development, even when they were overlooked in planning practice. From Roman Duklja to the Ottoman nucleus of Stara Varoš, earlier settlements adapted to the landscape (Figure 19) (ZEJNILOVIĆ; HUSUKIĆ, 2019, p. 55–56; MILIĆEVIĆ et al., 2023, p. 260; ĐUKIĆ; VUKSANOVIĆ-MACURA, 2018, p. 125–137). The 1879 urban plan by Vorman introduced a geometric, orthogonal layout for Nova Varoš that largely disregarded the natural terrain. Postwar socialist planning reinforced this model, treating the rivers primarily as peripheral green corridors rather than integrating them into civic life (POPOVIĆ; LIPOVAC; VLAHOVIĆ, 2016, p. 66–68; KOMATINA; KOSANOVIĆ; ALEKSIĆ, 2016, p. 52–55; ĐUKIĆ; VUKSANOVIĆ-MACURA, 2018, p. 125–137). Despite occasional moments of more visionary planning, the twentieth-century riverbanks remained underdeveloped — evidence of a persistent disjunction between urban morphology and city topography (Figure 20).

It is precisely along this neglected threshold that Radević positions Hotel Podgorica. By anchoring the building to the river, she proposes a strategy that stitches together the fractured edge between Nova Varoš, Stara Varoš, the riverbanks and the ruins of Ribnica, turning a residual zone into a hinge. The hotel’s landscape-driven tactics can be read as a quiet strategy for reconnecting marginalised parts of the city—using the river and its terrain as shared ground rather than as a limit.

Radević’s approach did not emerge in isolation. A few years earlier, in 1960, Vukota Tupa Vukotić completed his project for Labud Plaža, a riverside kayaking club along the Morača. As in Hotel Podgorica, cantilevered concrete terraces hover above the ground and pebbles from the river are embedded in the surfaces, fusing material and landscape in a single gesture. Radević would have known this work; her response can be understood as a continuation of this sensibility, reimagining the city’s relationship to the river and linking the two projects not only typologically, but physically along the riverbank.

Figure 21 – Labud Plaža on the banks of the Morača (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 22 – Labud Plaža on the banks of the Morača (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

In this sense, Radević’s architecture does not function as resistance in an overtly oppositional way, but as a support for another logic of the city — one not based on abstraction and order alone, but on continuities already present in the context. While the new Titograd was being shaped through hierarchy and simplification, her hotel introduces multivalence and duration. It acknowledges its place within the socialist city, yet does not fully adopt its rhetorical tools. It neither monumentalises nor erases; instead, it resists the impulse to overwrite and opens a different, more careful way for the city to grow.

What emerges, then, is another kind of urban landscape—one shaped not only by plans and ideologies, but by a fluid materiality that allows the city to remain open to its own sedimented history, and to its possible futures.

IV. The landscape of Yugoslavia: Between Monument and Memory

In the postwar years, Yugoslavia embarked on one of the most ambitious programmes of state-sponsored monumental construction in Europe. From Bosnia to Macedonia, spomenici were erected to commemorate the People’s Liberation Struggle. These were not statues in the classical sense, but vast sculptural forms intended to embody unity, sacrifice and socialist futurity. They turned landscapes into ideological theatres, reshaping hills, fields and forests into platforms for collective memory.

One of the most radical voices in this landscape was Bogdan Bogdanović—architect, writer and Radević’s teacher at the University of Belgrade. His projects stood apart from the official socialist canon in their turn toward archetypal imagery and spatial symbolism. His first major work, the Sephardic Jewish Cemetery monument in Belgrade (1952), marked a turning point in Yugoslav memorial architecture (SPOMENIK DATABASE, 2025), inaugurating a new architectural language for the construction of national memory (Figures 23 and 24).

Figure 23 – The Sephardic Jewish Cemetery monument in Belgrade (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 24 – The Sephardic Jewish Cemetery monument in Belgrade (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Rejecting Socialist Realism, Bogdanović developed a symbolically rich yet abstract language. The monument consists of a processional path flanked by low stone walls and triangular pylons, culminating in a menorah. Rather than imposing a new order, the structure is embedded within the existing cemetery, merging with its terrain and materiality. He incorporated fragments of bombed Jewish neighbourhoods—graves, rubble, stones—into the monument itself, turning it into a literal and figurative landscape of memory (SPOMENIK DATABASE, 2025).

Bogdanović rejected the idea that monuments should dictate meaning. He imagined them as spatial myths—open, poetic, supra-ethnic. His “anti-monuments” were not meant to speak for the state but to keep the field of meaning open. Architecture, for him, should not resolve history, but hold space for multiple, irreducible layers of loss and experience. He sought to reach what he called “a shared, presumably anthropological memory” (BOGDANOVIĆ, 1986: 17–19).

Svetlana Kana Radević rarely built memorials. Her most direct engagement with this typology is Barutana, the Monument to Fallen Fighters near Podgorica, completed in 1980. The complex honours soldiers and civilians from the Lješanska nahija region who died in the Balkan Wars, the First World War and the Second World War. It includes an amphitheatre for public gatherings—a space of remembrance where ceremonies sustain historical memory across generations (SPOMENIK DATABASE, 2025).

Figure 25 – Barutana Memorial Complex (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Figure 26 – Barutana Memorial Complex (Source: Photograph by the author, 2025).

Visitors do not arrive along a grand axial path, but move through a sequence of rounded gathering spaces—evocative of fire circles—before ascending toward a fractured constellation of concrete pylons. There is no singular focal point; one stands within a dispersed field of forms (Figures 25–26). As sunlight passes through the sculptural elements, the monument subtly evokes the presence of an ancient sundial, allowing time to be registered by nature itself, through the movement of the sun.

Radević recalled a childhood memory that shaped her thinking about the project—one she illustrated during an interview: “It was a circle with 12 divisions and a stick in the center. We waited for the shadow to move like a clock hand—but it didn’t jump. It flowed. We could see it shifting, but never the exact moment it moved. That mystery made us return again and again. It became a place of gathering and reflection” (RADEVIĆ, 2013).

This idea—time not as a fixed sequence but as a shifting presence—infuses Barutana. The monument does not declare a single meaning; its spatial experience unfolds gradually: in the play of shadow across pylons, in the slowness of scale. In this way, Barutana performs time rather than narrates it. As Radević notes, “Architecture is not just an adventure of space and materials. It is a form of social engagement that transforms aesthetics into an ethical act” (RADEVIĆ, 2013).

Her approach, though close to Bogdanović’s ethical stance, shifts the emphasis. Where Bogdanović works through myth and archetype, Radević turns toward the present—toward elements that unite experience: light, terrain, shadow, water. For her, tradition is not something to be symbolically referenced, but something to be continued and lived. She takes from Bogdanović the conviction that architecture should not dominate memory, but make room for it. Within the broader project of constructing Tito’s new socialist state — which often relied on monumental forms to stabilise a collective narrative—her work offers a quieter, parallel path. Her work does not monumentalise trauma, nor does it erase it; it incorporates the past into the present and works with the landscape as it is.

V. The landscape of Kana

Already at twenty-nine, Svetlana Kana Radević received the Federal Borba Prize for Hotel Podgorica—becoming the youngest architect, and the only woman, to receive Yugoslavia’s highest architectural honour. The award brought her national visibility and set the course for a distinctive career. She studied with Louis Kahn in the United States and worked with Kisho Kurokawa in Japan, yet chose to return to Montenegro, grounding her practice in a region where material and memory framed her way of working.

Since then, the city around Hotel Podgorica has changed. Titograd became Podgorica; Yugoslavia dissolved. Her buildings entered a new economy. Although now celebrated—with appearances at the 2004 Venice Biennale and in MoMA’s Toward a Concrete Utopia (2018)—the hotel has also faced neglect and alteration. Privatised in 2004, it underwent renovations that compromised its original interior, prompting public and professional concern (KATS, 2020).

Post-socialist urban development in Podgorica has frequently prioritised private profit over public interest and heritage. Deregulation enabled unrestrained construction, often on public or green land, with legal instruments used to legitimise ad hoc interventions (VUJOŠEVIĆ et al., 2018). In this context, the careful reciprocity between building and river that structured Hotel Podgorica appears increasingly exceptional.

In 2015, a group of young architects founded KANA (Ko ako ne arhitekta? / “Who, if not the architect?”), organising campaigns to protect the hotel and its surroundings—including protests against a neighbouring office tower that threatened its integrity (VUJOŠEVIĆ et al., 2018). Their actions form part of a broader struggle to preserve modernist legacies amidst speculative urban transformation. Radević’s name became a rallying point—not only against architectural erasure, but against the loss of public space and collective memory.

Hotel Podgorica remains unprotected by heritage law. It now stands both as an architectural landmark and as a measure of cultural fragility. The office tower pressed against it exemplifies the very logic her project once resisted: a mode of building that disregards natural context while capitalising on symbolic value (Figure 5). Against this backdrop, the “landscape of Kana” is no longer only the riverbank she built into, but also the contested terrain of institutions, regulations and civic initiatives that continue to shape, and to test, the endurance of her work.

VI. Conclusion – The Landscape of Time

What is a landscape, still? Is it an image, a setting, a memory, a surface, a terrain? The term remains unstable—its meanings shifting across disciplines, languages and histories. It is precisely this instability that makes it a ground for rethinking architecture. Svetlana Kana Radević never theorised landscape. She built it.

Her buildings do not aspire to depict nature. In Hotel Podgorica, the river is not a view but a participant. The hotel does not simply sit beside the Morača—it takes up its logic. It echoes the river’s movement, direction and rhythm. The terrain is not a backdrop but an active presence. Concrete, fractured stone, shadow and flow all take part in the construction of time. In this sense, her work resonates with Latour’s idea that time is not a neutral backdrop for events, but a relational weave of material processes and encounters (LATOUR, 1993). Time is not simply passed through; it is produced.

This attitude does not grow out of a theoretical system, but from a situated sensitivity to place. Like Bogdanović — whose work drew on myth, landscape and memory without relying on manifestos — Radević proceeds through observation, intuition and material attunement: in how a wall turns in relation to a slope, how a path follows a contour, how a river might be allowed to shape a building’s course. Her method is neither doctrinal nor decorative; it is responsive.

Radević’s practice is grounded in spatial judgment—an ethic formed by context rather than by programme. She did not leave manifestos or rhetorical proclamations; she left buildings that engage their surroundings with care and precision. Hotel Podgorica is not a monument but a presence, not a declaration but a site of relation. It gathers river, city, history and use into a slow composition, proposing a way of understanding landscape as image, ground and duration at once, and offering in built form an answer to the question with which this essay began: what does it mean to build not upon, but with, the land?

Bibliography

ALIHODŽIĆ, Rifat – Arhitektura u Crnoj Gori 1965–1990. (Kroz prizmu “Borbine” nagrade). Podgorica: CANU, 2015

BOGDANOVIĆ, Bogdan – Smrt i grad. Beograd: BIGZ, 1986.

BOGDANOVIĆ, Bogdan – Symbols in the City and the City as Symbol. In: EKISTICS, vol. 39, nº 232, Mar. 1975, p. 140–146. ISSN 0013-2942. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43618476. Accessed on: 13 July 2025.

BOGDANOVIĆ, Bogdan – Town and town mythology. Ekistics, Vol. 35, No. 209, A city for human development: a three day symposion, abril 1973, p. 240-242. Disponível em: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43618148. Accessed on: 13 jul. 2025.

ĐUKIĆ, Aleksandra; VUKSANOVIĆ-MACURA, Zlata – Expansion of the planned city in relation to the historical core: The case of Podgorica, Montenegro. In: Cities, vol. 82, 2018, p. 125–137. ISSN 0264-2751. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.05.001.

HARTSHORNE, Richard – The Nature of Geography: A Critical Survey of Current Thought in the Light of the Past. Lancaster, PA: Association of American Geographers, 1939

INGOLD, Tim – The Temporality of the Landscape. In: WORLD ARCHAEOLOGY, vol. 25, nº 2, 1993, p. 152–174. ISSN 0043-8243.

KATS, Anna – Svetlana Kana Radević (1937–2000). In: THE ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW, 13 Mar. 2020. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/reputations/svetlana-kana-radevic-1937-2000. Accessed on: 13 July 2025.

KOMATINA, Dragan; KOSANOVIĆ, Saja; ALEKSIĆ, Julija – Urban Devastation: The Case Study of Podgorica, the Capital of Montenegro. In: ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING, vol. 12, 2016, p. 52–55. ISSN 2255-8764. https://doi.org/10.1515/aup-2016-0014.

LATOUR, Bruno – We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-674-94839-4.

MILIĆEVIĆ, Nemanja; ALIHODŽIĆ JAŠAROVIĆ, Ema; VANIŠTA LAZAREVIĆ, Eva; MARIĆ, Jelena – The Historical Processes of Transformation of the Space through Urban Design Competitions: The Case Study of Independence Square in Podgorica. In: Places and Technologies 2023 – 8th International Academic Conference, Belgrado: University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture, 2024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18485/arh_pt.2024.8.ch30.

MITCHELL, W. J. T. – Landscape and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-226-53221-4.

OLWIG, Kenneth R. – Recovering the Substantive Nature of Landscape. In: ANNALS OF THE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN GEOGRAPHERS, vol. 86, nº 4, 1996, p. 630–653. ISSN 0004-5608. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2564345. Accessed on: 14 Sept. 2016

POPOVIĆ, Svetislav G.; LIPOVAC, Nenad; VLAHOVIĆ, Sanja – Planning and Creating Place Identity for Podgorica as Observed Through Historic Urban Planning. Zagreb: Faculty of Architecture, University of Zagreb, 2016. (Prostor, Vol. 24, nº 1(51), p. 62–73). ISSN 1330-0652..

PEROVIĆ, Svetlana K.; BAJIĆ ŠESTOVIĆ, Jelena – Creative Street Regeneration in the Context of Socio-Spatial Sustainability: A Case Study of a Traditional City Centre in Podgorica, Montenegro. In: SUSTAINABILITY, vol. 11, nº 21, 2019, art. 5989. ISSN 2071-1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215989.

ROVČANIN PREMOVIĆ, Gordana – Expansion of the Planned City in Relation to the Historic Urban Structure: Case Study Podgorica, Montenegro. Istanbul: Journal of Ottoman Legacy Studies, 2020. (Vol. 7, nº 18, p. 347–358). ISSN 2148-5704. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17822/omad.2020.161

SCALBERT, Irénée – Architecture as Nature. In: RA. REVISTA DE ARQUITECTURA, nº 20, 2018, p. 12–21. ISSN 1138-5596. DOI: 10.15581/014.20.12-21

STAMATOVIĆ VUČKOVIĆ, Slavica; BULATOVIĆ, Danilo – Modernism in the Petrified Landscape: Architecture in Montenegro 1945–1980. In: ACE: Architecture, City and Environment, Vol. 15, nº 43. Barcelona: UPC, 2021. e-ISSN 1886-4805. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5821/ace.15.43.9213

TILLEY, Christopher – A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1994. ISBN: 978-1-85973-021-2.

VUJOŠEVIĆ, Milica; DRAGOVIĆ, Sonja; RABRENOVIĆ, Jelena; DRAGANIĆ, Ružica – Planiranje protiv grada: Kako su javni prostori i kulturna baština žrtvovani privatnim interesima povlašćene manjine. Podgorica: Centar za istraživačko novinarstvo Crne Gore e NVO KANA / Ko Ako Ne Arhitekt, 2018. ISBN 978-9940-9868-2-7.

WORRINGER, Wilhelm – Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style. Trad. Michael Bullock. Introd. Hilton Kramer. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997. ISBN 1-56663-177-7.

ZEJNILOVIĆ, Emina; HUSUKIĆ, Erna – City in Transition: Podgorica, Europe’s Youngest Capital City. In: Frontiers of Architectural Research, Vol. 8, nº 1, 2019, p. 55–65. [S.l.]: KeAi / Elsevier. ISSN 2095-2635. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2018.12.004. Disponível em: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

RADEVIĆ, Svetlana Kana – Architecture is my today and my tomorrow. Interview by Pobjeda, 23 July 1967.

RADEVIĆ, Svetlana Kana – Interview with Svetlana Kana Radević [Online]. YouTube, published by Giordano Angelo, 2013. Available at: https://youtu.be/SVAkClyID8E?si=kOAu09MAPOdFpEJ7. [Accessed 13 July 2025].

SPOMENIK DATABASE – Available at: https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/. Accessed on: 13 July 2025.