Rebecca Billi

billirebecca@gmail.com

Researcher and Ph.D. Candidate at Universidade Autonoma de Lisboa. Itália.

To cite this article: BILLI, Rebecca – A palace for a Baroque Urbanist. The rhythm of Sant’Ambrogio Casa Caccia Dominioni and Architecture as a Continuum. Estudo Prévio 27. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, dezembro 2025, p. 47-72. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Disponível em: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/27.3

Received on July 16, 2025, and accepted for publication on October 26, 2025.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

A palace for a Baroque Urbanist/ The rhythm of Sant’Ambrogio Casa Caccia Dominioni and Architecture as a Continuum

Abstract

In 1947, in the wake of the city council’s postwar reconstruction scheme, architect Luigi Caccia Dominioni took it upon himself to give new life to the bombed remains of his family palace on Piazza Sant’Ambrogio in Milan. This article aims to explore the approach to architecture in Milan during the post-war reconstruction period through an examination of the concepts of temporality, tradition, and the specific case of Casa Caccia Dominioni. The building is to be read both as a model to deal with modernity within history and context, and as a foundational work for the development of Caccia Dominioni’s language, popularised by Gio Ponti as “Stile di Caccia.” The work questions the specific relevance of this work by Caccia in light of his subsequent production and following Agnoldomenico Pica’s claim that it represented the synthesis of what postwar restoration ought to be. These statements are explored through critical work produced following the “rediscovery” of Caccia’s work at the beginning of the 21st century, along with archival material, direct observation, and visual documentation. The research is centred on an architectural reading of the palace and an intention to dissect the way Caccia makes use of ‘memory’ in his work, counterposed to the theoretical reading given by Ponti to concepts of tradition and reconstruction. The archival and literary research is integrated with individual interviews with architects and scholars Cino Zucchi and Simona Orsina Pierini.

Keywords: Caccia Dominioni, Milan, Postwar Architecture, Modernity, Tradition.

Introduction

Figure 1 – Casa Caccia Dominioni, 1925 (Source: Unknown Author. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/MilanoScomparsa [Acc. 01/07/2025]).

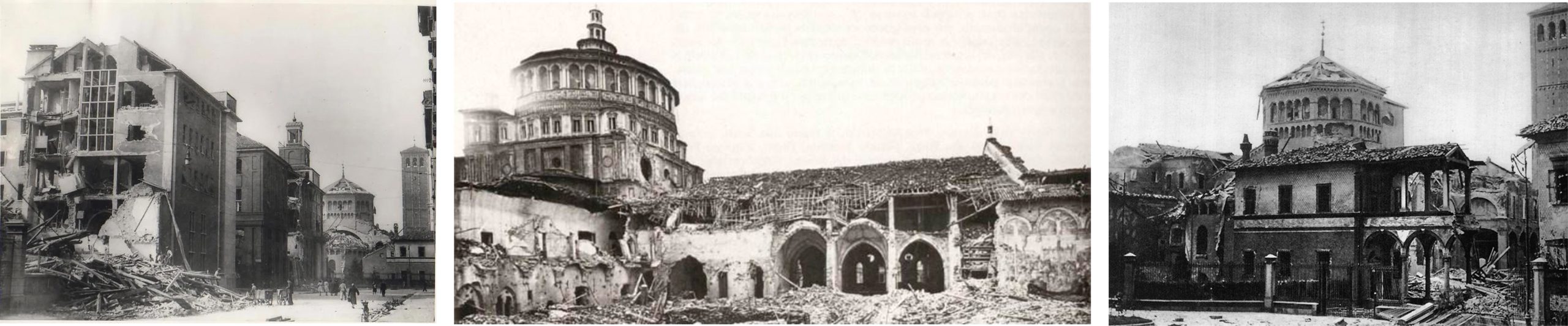

Within the old ring of the now-buried Navigli, Sant’Ambrogio has borne testimony to many Milanese eras and trends. On the corner, coming from Via San Vittore, the old palace of the aristocratic Caccia Dominioni family has stood for decades, until the bombing of World War II not only destroyed the edifice but also erased the stories and memories inscribed within (Figure 1). The same site has housed a palace, bombed remains, scaffolding… (Figures 2 to 4). As a square and church, Sant’Ambrogio is both the backdrop against which all these roles were played and the combination of architectural and social relationships without which they would not hold up; all survive not only in pictures but also in the postwar edifice that inherited the title of Casa Caccia (Figure 2).

It was Luigi Caccia Dominioni (1913-2016), scion to the family name and palace, who in 1947 took it upon himself to give new life to the bombed remains of the building. Milanese with origins from Trentino, Caccia was a nobleman and grew up in the city’s upper class. During his very long and prolific life, he produced a vast number of residential and commercial buildings in and outside of Milan. All were defined by his contradistinctive language of modernity and tradition. Among Caccia’s production, the house in Sant’Ambrogio stands out as his first proper built commission and, as I will explore in the text, a manifesto for his later work. I will claim that it embodies the transformations of Milan and the expression of that idea of building according to tradition, inherently ‘Italian,’ advocated by Gio Ponti throughout the pages of Amate l’Architettura (PONTI, 1957). Furthermore, I shall present Casa Caccia as a model to deal with modernity within history and context –preceding later discussions on construction in heritage centres– and the synthesis of a paradigm for reconstruction emerging from ‘the house.’

Figure 2 – Casa Caccia Dominioni, 1920 (Source: Unknown Author. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/MilanoScomparsa [Acc. 01/07/2025]). Figure 3 – Casa Caccia Dominioni after the bombing, 1943 (Source: Unknown Author. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/MilanoScomparsa [Acc. 01/07/2025]). Figure 4 – Casa Caccia undergoing construction, s.d.(Source: Archivio Civico di Milano. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture/schede/3m080-00050/ [Acc. 11/07/2025]).

The construction of the ‘new’ Casa Caccia was completed between 1947 and 1949, in its original lot at number 16 of Piazza Sant’Ambrogio. Mostly intended for residential use, the ground floor included spaces for shops and artisans, now housing different businesses, including a small gym. As introduced above, this article sets out to answer the question of how the palace functions as a funding manifesto of Caccia’s oeuvre and, simultaneously, represents the synthesis of a new paradigm for reconstruction in Milan in the wake of the destruction of World War II, negotiating modernity within historical and contextual frameworks. Addressing this, the article poses the building as relevant on two planes of significance: both for postwar Milanese architecture and for the development of Caccia’s architectural expression. An expression that stands out as entirely his own, so distinctive to be popularised as “Stile di Caccia” by Ponti (PONTI, 1941: 28-33). Recognising that Milan represents a singularity and a conglomerate of eclectic excellence within the panorama of modern architecture in Italy, as well as throughout Europe, the body of the article develops following a top-down approach: to understand the urban context first and secondly explore how ‘tradition’ is perceived in this specific moment in time, then focusing on the emergence of Caccia’s language. In order to contribute to the discussion on Caccia Dominioni’s work, I will delve into the reasons why this one building holds critical relevance for architectural history and the development of his author’s freedom of expression.

Regardless of Caccia’s popularity with the Milanese ‘sciure,’ who were eager to present themselves as hostesses of a “casa del Caccia,” he has been largely absent from both the academic narrative and the popular canon of modern Italian architecture up till around 20 years ago [1]. Scholar Lorenzo Finocchi Ghersi wonders why that is. He blames it on Caccia’s engagement with the centre of the city rather than with the suburbs, but that appears to be an incomplete hypothesis, considering that he did indeed conduct work at the outskirts of Milan (FINOCCHI GHERSI, 2022: 64). Many theories can be carried out, some more relevant than others. The fact remains that the production on Caccia Dominioni can be divided into two main blocks, with a gap between the two covering the last decades of the 20th century.

Figure 5 – The façade of Casa Caccia, Piazza Sant’Ambrogio, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi).

A written production taken out by his contemporaries exists and is found in the pages of magazines such as Domus, Abitare, Superfici, Ottagono, Vitrum, and Casabella. Mostly devoid of theoretical critique, it accompanied the completion of his architectural works. It is only in 1984 that Giacomo Polin’s article in Casabella gives Caccia Dominioni key critical recognition. (POLIN, 1984: 42) Unlike his contemporaries Luigi Moretti or Ernesto Nathan Rogers, Caccia was not in the habit of committing to paper his architectural theories, preferring to let the buildings themselves do the talking. In the early 21st century, academia and the critical field gained new interest in his work, especially due to the engagement of professionals like Cino Zucchi, who brought Caccia Dominioni’s architecture to not one, but two Venice Biennales (Figures 6 and 7). The work of scholars Elli Mosayeby, who centred her Phd Thesis on the architect’s “construction of ambients” (MOSAYEBI, 2014), and Mónica Alberola Piero, who recently published her research on his “exercises of style” (ALBEROLA PIERO, 2023), has been particularly relevant to the ‘rediscovery’ of Caccia’s work and to gaining new critical insights on his production. [2] The most complete texts on Caccia Dominioni have been published from the early 2000s onwards, often accompanying the production of exhibitions on the architect. These include Luigi Caccia Dominioni: stile di Caccia. Case e cose da abitare by Fulvio Irace and Paola Marini, a companion book to the eponymous exhibition held in Verona in 2002; Everyday Wonders/Meraviglie Quotidiane by Cino Zucchi and Innesti/Grafting by Zucchi and Nina Bassoli, respectively published as the catalogues of the 2018 and 2014 Venice Biennale contributions they curated. [3] Drawings and archival materials on Caccia’s work are collected in Milan, divided between the Archivio Caccia Dominioni, managed by the architect’s heirs and situated in Casa Caccia itself, the Municipal Archive of Milan, and the Archive of the city’s Order of Architects.

Figure 6 – Cappelle della Casa Caccia Dominioni, Biennale, 2014 (Source: Marina Caneve, Zucchi Architetti. Available at: https://www.zucchiarchitetti.com/ [Acc. 11/07/2025]) Figure 7 – Everyday Wonders, Biennale, 2018 (Source: Cino Zucchi, Zucchi Architetti. Available at: https://www.zucchiarchitetti.com [Acc. 11/07/2025]).

In this research, to better understand the character and architectural view of Caccia Dominioni, I will make use of the aforementioned books by Irace and Marini, and by Zucchi, integrated with the lecture given by Mosayebi at The Berlage Centre at TU Delft. (MOSAYEBY, 2019) Volume 2 of Innesti/Grafting by Zucchi and Bassoli serves as a guide to connect Caccia’s own experience and the context of post-war ‘modern’ Milan. This is also aided by the texts in Robert Lumley and John Foot’s Le Città Visibili, while Case Milanesi by Orsina Simona Pierini and Alessandro Isastia will guide the understanding of the societal role of the house in Milan. Information and graphics on the extensive surveys and mapping carried out in the city after the end of World War II and in preparation for the restoration works come from the website of the Comune di Milano and are presented extensively in Gianfranco Pertot and Roberta Ramella’s book Milano 1946. I will make use of Ponti’s text, Amate l’Architettura, to give critical context and gain better insight into the theoretical lens through which memory, tradition, and reconstruction were understood and applied in this peculiar historical time in Milan. On the other hand, I shall draw on Stendhal’s depictions throughout his writings to recreate an impression of the city before the war. The archival and literary research carried out for this work is furthermore expanded and integrated with individual interviews I conducted in April 2025 with architects, scholars, and Caccia-Dominioni-experts Cino Zucchi and Simona Orsina Pierini, who generously shared with me their time and insights on this distinctive figure of Milanese architecture.

This methodological combination of different sources is the distinctive aspect of the research. Building upon the written production already existing, it employs the methods and instruments that are inherent to architectural practice, enriching its academic counterpart. In this way, the article looks at Casa Caccia with the aim of not only exploring a question but also the approaches that, as architects, we can employ in the practice of research. Theory and bibliographic references support the investigation of archival material. Analysed through an architectural lens and praxis of visual documentation, they give insights into the times and the building that practically allowed Caccia to test the first iteration of a distinctive architectural language. The interviews and direct observations, both on-site and from the drawings, are appropriate within the framework of an architectural research practice. Precedents and contextual events are observed not to celebrate the persona of Caccia, but to explore an architectural process. This intention is situated within a wider design to present different positions in modernity, rather than the validation of a singular solution to urban challenges. Moreso, looking at the process also opens the door for future further research into covert or direct influences of Caccia on the work of contemporary architecture practices, like Sergison Bates and early Herzog and de Meuron.

I Contextualisation

Milan After World War II: Reconstruction and Tradition, and the Evolution of the Milanese House

Figure 8 – Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, s.d. (Source: Unknown author. Available at: https://files.cdn-files-a.com/uploads/2369425/normal_64d2b96fe1e6f.jpg [Acc. 11/07/2025]). Figure 9 – Santa Maria delle Grazie, 1943 (Source: Unknown author. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Milano_Bombing_1943.jpg [Acc. 11/07/2025]). Figure 10 – Sant’Ambrogio, 1943 (Source: Author unknown. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Distruzione_Sant%27Ambrogio.jpg [Acc. 11/07/2025]).

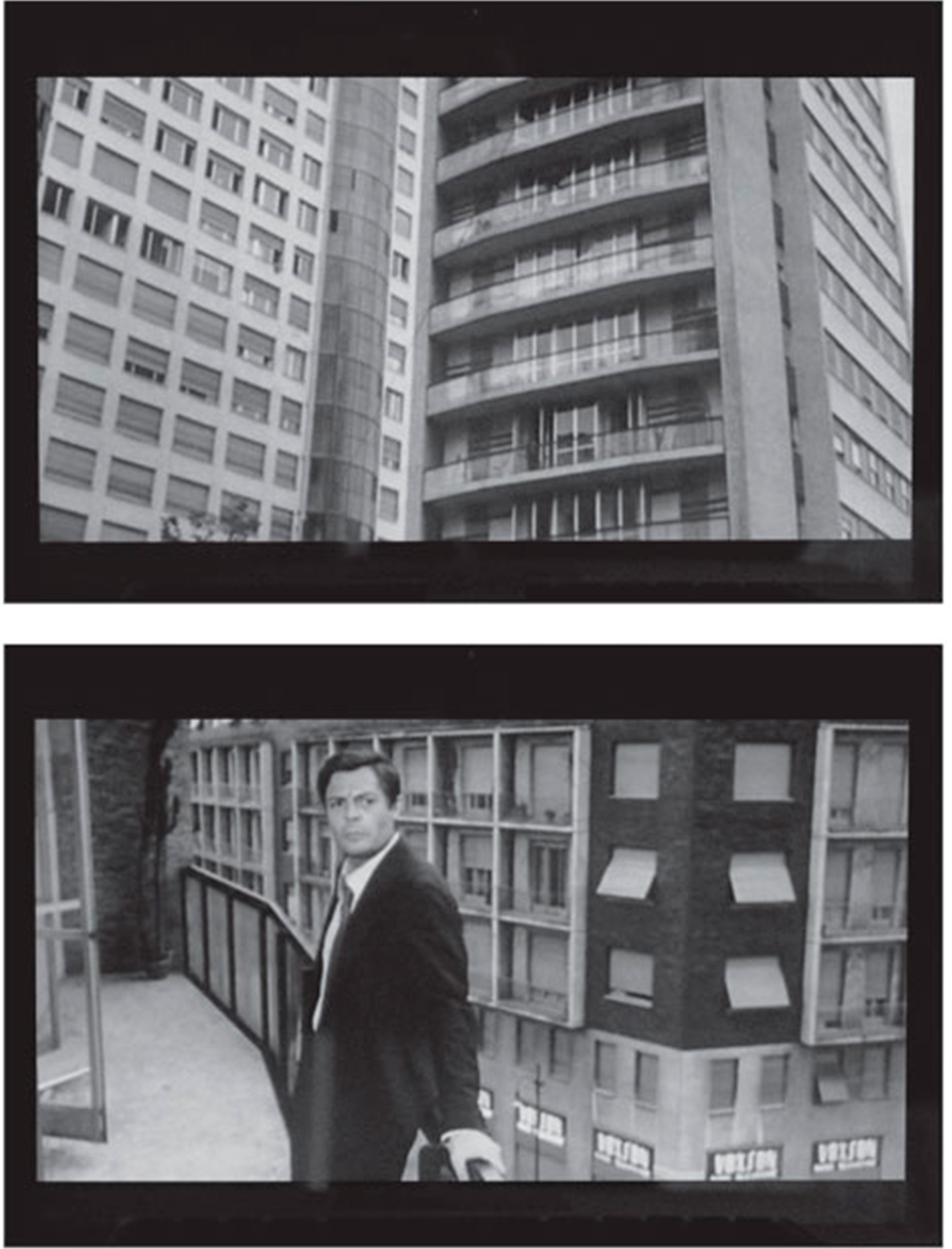

Between 1940 and 1944, Milan was repeatedly bombed. Standing out as one of the most damaged cities in the Country, it was the most affected one in northern Italy (Figures 8 to 10). The bombing happened punctually throughout the city, creating gaps and urban voids (Figure 11). This pattern of destruction shaped a unique approach to reconstruction. Milan was not completely taken down like Rotterdam was (which brought about a reconstruction strategy based on radical modernism and tabula rasa), nor systematically destroyed like Warsaw (later meticulously rebuilt). It also represents an exceptional case in the Italian context, as the bombing would generally be focused on specific areas of the city, as was the case with Naples, where they bombed the port, or Florence, with the bridges. In the aftermath, it became clear to the local council that reconstruction would require a specific strategy able to respond to the characteristics of the damaged existing fabric in the city centre.

Figure 11 – Mapping of the wartime destruction of Milan’s city centre, 1969 (Source: Bruno de Finetti. Available at: https://www.storiadimilano.it/Repertori/bombardamenti.htm [Acc.11/07/2025]).

Briefly deferring from the subject at hand to better understand the framework of architectural production that Caccia operates within, I want to point out how the aspect of the centrality of context has always been a recurring topic for architecture in central Milan, yet gains new traction from the reconstruction onwards. The common strategy, mostly popularised by the work of Asnago & Vender, can be broken down to the act of dividing the newly built into two bodies of opposite scales, where the low one stands on the street and the high one rises at the back. [4] In this way, the front responds to the dimensions and proportions of the context, while the back is defined by formal freedom and scale (Figures 12 and 13). It is not the case of Casa Caccia, but it is important to comprehend what was happening around Milan to properly perceive how his approach is so singular and important in rethinking the shared method. Interestingly, the neighbouring building at number 14 of Piazza Sant’Ambrogio was built anew by those same Asnago & Vender (Figure 14).

Figure 12 – Condominio XXI Aprile from Piazzetta San Josemaria Escrivà, s.d. (Source: Alessandro Sartori, Available at: https://oami.s3.eu-south 1.amazonaws.com/legacy/cache/arch_img_big/media/resize/copy/197/20131206125041-DSCF0236_m_800x600px.jpg [Acc. 11/07/2025]) Figure 13 – Condominio XXI Aprile, The high body, s.d. (Source: Alessandro Sartori, Available at: https://oami.s3.eu-south-1.amazonaws.com/legacy/cache/arch_img_big/media/resize/copy/197/20131206125109-DSCF0230_m_800x600px.jpg [Acc. 11/07/2025]) Figure 14 – Piazza Sant’Ambrogio 14, 2005 (Source: Daniele Garnerone. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/assets/immagini/liv1/A310RL/SC/A/3m080/00/A_3m080-00028_IMG-0000192449.jpg. [Acc. 11/07/2025])

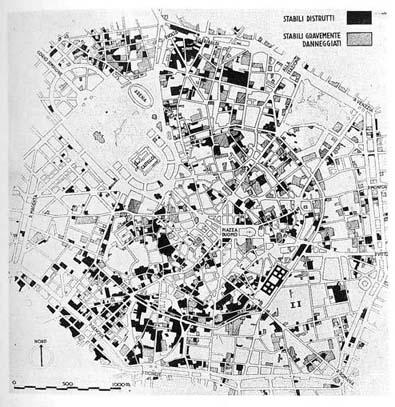

Going back to 1946, that year, the Milan City Council called on local architects to conduct an extensive survey of the city. They listed all the buildings and their current state, including urban voids, constructions destroyed during the conflict, and damaged ones. For each building, it detailed the level of wreckage (Figure 15). The value of this map lies not only in the fact that it drew an exact image of the city conditions in the wake of World War II, but it also set the tone for the way the restoration would happen (Figure 15). The architects who compiled it were local, aware of Milan’s urban fabric and character, and would be the ones asked to rebuild it. Caccia Dominioni was part of this group. The survey revealed that Milan would require a ‘delicate’ reconstruction, one that would work through fragments and grafts, with modern buildings inserted into the gaps caused by the bombs within the pre-existing fabric. It was not about designing a new city, but rather intervening punctually to rebuild upon the city itself – the way Milan has always grown urbanistically. All of this had to happen according to Italian tradition and ‘stile.’

Figure 15 – Piazza Sant’Ambrogio, Via San Vittore, 1946 (Source: Alberto Morone. Available at: https://www.comune.milano.it/servizi/rigenerazione-urbana/cartografie-storiche-di-milano-censimento-urbanistico-1946 [Acc. 11/07/2025]) Figure 16 – Table 77, Duomo, 1946 (Source: Archivio Comunale di Milano. Available at: https://www.comune.milano.it/servizi/rigenerazione-urbana/cartografie-storiche-di-milano-censimento-urbanistico-1946 [Acc. 11/07/2025])

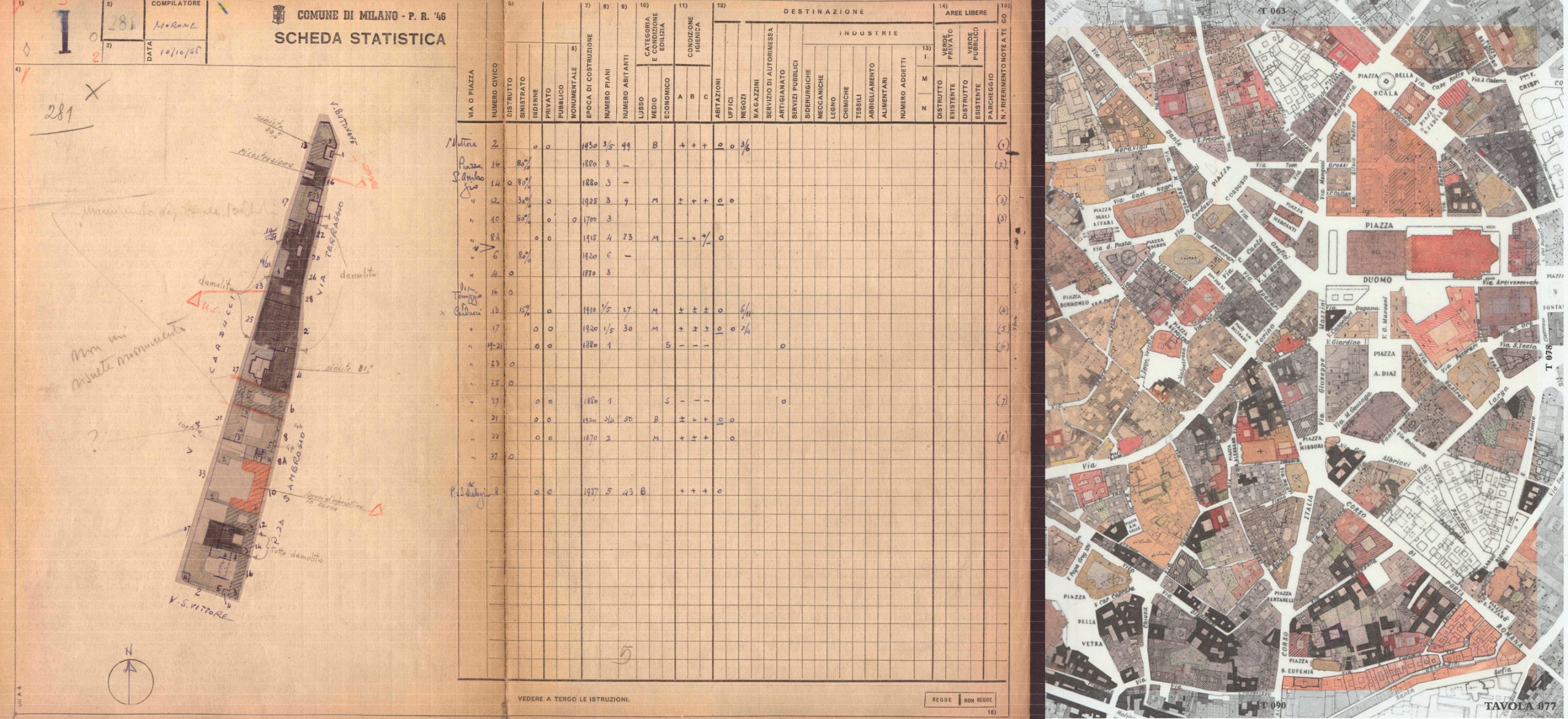

This process of enquiry into how to approach reconstruction opens the door to a theoretical discourse amongst architects and intellectuals about what ‘tradition’ means and its declination in the Italian context. According to Ponti, to build according to tradition means “to do new things in a new way (as they ought to be done if they are new), doing them as well as they were done five hundred years ago.” (PONTI, 1957: 99). It is in the way things are done, not in the shape given to them, that the tradition of built work in Italy lies. ‘Tradition’ is a practice and a memory of method, and the innermost character of Italian architecture that unifies the diverse production manifested across the peninsula (PONTI, 1957: 108). Ponti goes on to say that “of the ancients we preserve the ‘stile’ that is, the virtue: not ‘the styles’”– the method, not the formal outcomes (PONTI, 1957: 101). This means that, in postwar Milan, ‘style’ is understood as a way of doing things, a quality that unifies them, not their appearance. In line with this idea of tradition as praxis, it was of main importance for all the involved actors that the restored and the newly built did not copy or recreate either the existing or the destroyed edifices. It would not have fit the city’s urban identity nor the image of modernity it aimed to project. Nostalgia does not mark this era of Milanese life in any form. It is defined by industriousness and a dynamic urban vitality. Citizens found satisfaction in work, in the idea of “construction,” both theoretical but especially physical, which is –says philosopher and politician Antonio Banfi– “instinctively compensated for by a poetic and sentimental recall to traditional forms of life. Without, however, any real regret or desire to return.” (TORRICELLI, 2014: 1). Milan was looking forward, also through architecture (Figure 17).

Figure 17 – La Notte, 1961 (Source: Michelangelo Antonioni, Film Screencaptures).

The main critical discussion of the post-war period centred on the need for a new architecture. One that would be able to meet the requirements and represent this modern Milan as a city reconstructed upon itself according to tradition, reflecting the standards and practices ingrained in built production in Italy. It was to happen through the urban and societal characters that defined it contextually, together with an interiorisation of its own history. Irace speaks of the creation of an architectural koinè, a common language that he claims would allow “to make use of the idea of a ‘stile’ as belonging to the specificity of a time and the image of a pluralistic city amidst the essential unity of its forming skyline.” (IRACE, 2002: 19). An architectural language based on a shared method (or tradition) tying the city together while still allowing for individuality. The architects of the time are being asked to create an image of Milan.

Milan has always been made of multitudes, of diverse classes and social conditions. Regardless of the appearance of central areas, where a certain uniformity reigns, it is not an urban reality that exists as a cohesive whole, as much as a collection of unities. Above the rest, it is a coy city by nature. Milan hides and defends its heterogeneous identity through austere palaces and façades that conceal lively inner courts. It doesn’t immediately give access to the social rituals and dynamics that most often take place within private walls. In the early nineteen-hundreds, the French writer Stendhal came to Milan on numerous occasions, driven by a genuine enamourment with the city. He recalls his impressions multiple times and in various writings that bear witness to the increasing richness of the citizens and their investment in private architecture. (STENDHAL, 1813-1821/2016: 487) Stendhal smartly summarises the social dynamics woven into the built production as he writes that to commission a beautiful house is what confers true nobility in Milan (STENDHAL, 1816/1920: 36). The element of representation inscribed in private architecture is certainly not a novelty. In 20th-century Milan, it gained new resonance, manifesting in houses and apartments across social classes. Giovanni Muzio’s Ca’Brutta (1922), a private residence in the Brera neighbourhood, gives way to modern architecture in Milan. From 1946 onwards, the new architecture emerges from ‘the house,’ as the ideal place for formal experimentation and the epitome of Milanese identity. Furthermore, in a manner that is unique to the city and a result of its inherently bourgeois character, modernity was driven by private investment at a personal scale.

II The Building

Environments, context, and atmospheres

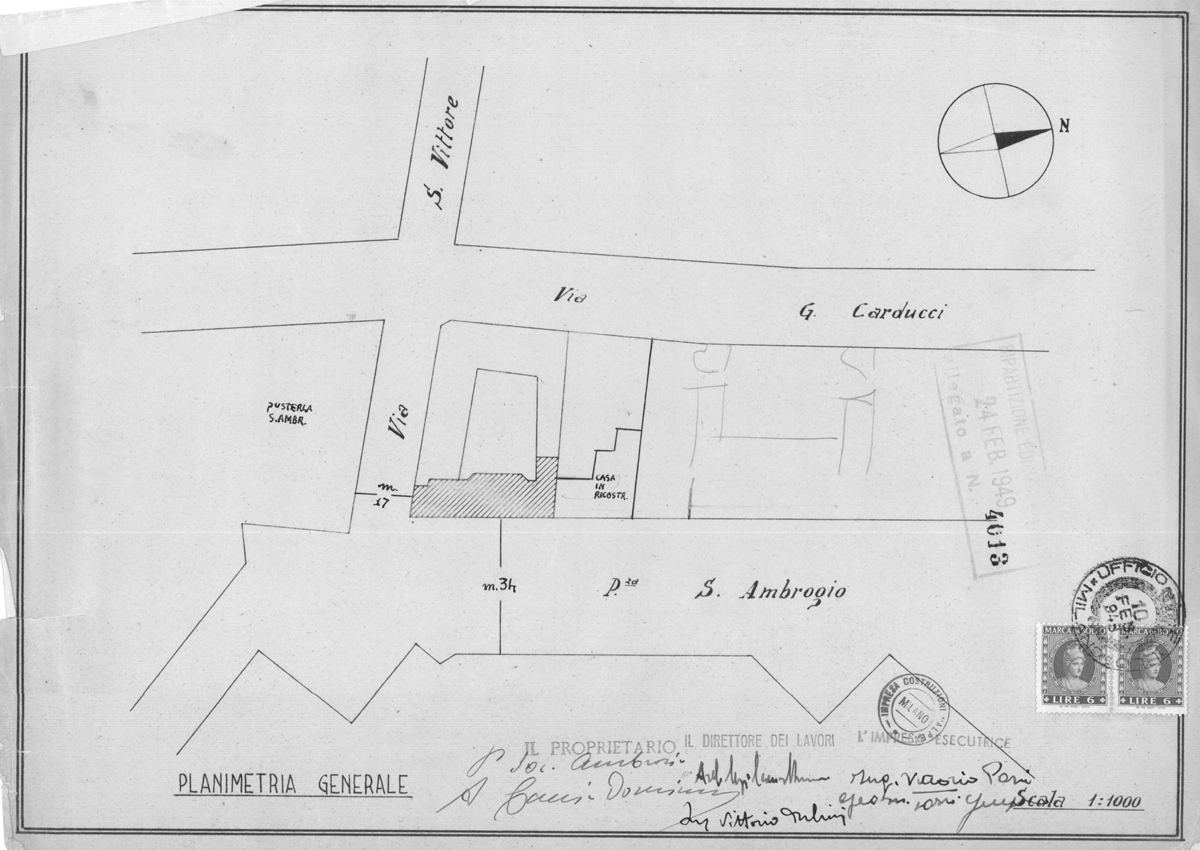

According to the dedicated page in the 1946 city survey compiled by architect Alberto Morone, the building at number 16 of Piazza Sant’Ambrogio, known as the residence of the Caccia Dominioni family – built in 1880 and comprising of three storeys– was left destroyed for 80% by the bombing of the city (Figure 15). Already actively involved in the reconstruction, architect and furniture designer Luigi Caccia Dominioni, the son of the building owner, was appointed by the family to build a new home for the household. In taking on this work, Caccia was aware that the project would come to involve an engagement with the existing realities that preceded his intervention – the palace itself, the square, and the neighbourhood (Figure 18). He is the first one to state, when recollecting the initial stages of the design process, that “it came spontaneously to adapt to the shape, the breath, the atmosphere of the Piazza” as he was conscious that the building had to be “a construction from Sant’Ambrogio.” (SACERDOTI and CIGARINI, 2005). Caccia approached the work aiming to create a building that would emerge from the environment, referring both to the place and the social context. It would have to partake of the feel of the square without directly copying the existing architectural elements, and he is conscious of the different relationships present in time and space in the site where he is building. These come together with an aristocratic taste, based on a learned sensibility and a series of inputs with which he has been in contact since childhood.

Figure 18 – General Site Plan, Casa Caccia Dominioni, 1947. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/?offset=1. [Acc. 15/07/2025]).

Through tradition and an object-centred conception of memory, he achieves a language of modernity that is attentive to the past but doesn’t mimic it as much as relate and respond to it. He rejects the tabula rasa of the strictest rationalism and engages with context in both its physical and temporal dimensions. Subsequently, Casa Caccia operates on multiple degrees of expression. Its architectural signs and symbols can be interpreted at a more or less superficial level. The depth of interaction is dependent on the attention and sensitivity of the observer, but is nonetheless always present. Caccia’s architecture is in dialogue with the existing language of the palace. Zooming out, it has to respond to the square, coming into the systems of materials and proportions that define the character of this part of the city. At the widest, comes temporality. This last degree of relationships the new building establishes is with Italian architecture, its history, and present manifestation (Figure 19).

Figure 19 – Casa Caccia and Sant’Ambrogio details, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi).

In Spazio, architect and critic Agnoldomenico Pica claims that Caccia’s work in Sant’Ambrogio is the best synthesis of what restoration should be (IRACE, 2002: 17). Irace highlights how Pica describes a process that goes beyond addressing the ravages of time and recreates the “hue of a past” by continuously reviving its spirit in the new (IRACE, 2002: 17). Of Casa Caccia, Pica says: “here, where everything has not only been remade new, but in new ways and intentionally free of traditional tolls, a true and proper restoration has been achieved, through the creation of an architecture that, in its environmental relationships (here as complex and challenging as ever), exactly sums up the part once played by the architecture that preceded it.” (IRACE, 2002: 17). It is a particularly relevant sentence as it gives an understanding of the importance given at the time to the atmosphere of the place, and of the city. Hence, the most important aspect of Casa Caccia is not that it was rebuilt anew where it stood. It is that in the architectural choices taken by Caccia Dominioni and through this new language of modernity and tradition, the palace managed to re-establish associations and relationships with its surroundings. It’s not the “retreat from Modernism” that Reyner Banham accuses Milanese architects of, but rather a pursuit of an Italian modern language (BANHAM, 1959: 231-235). Responding to local specificity, it establishes a clear theoretical and stylistic departure from the purist rationalism of Fascist architecture (Figure 20).

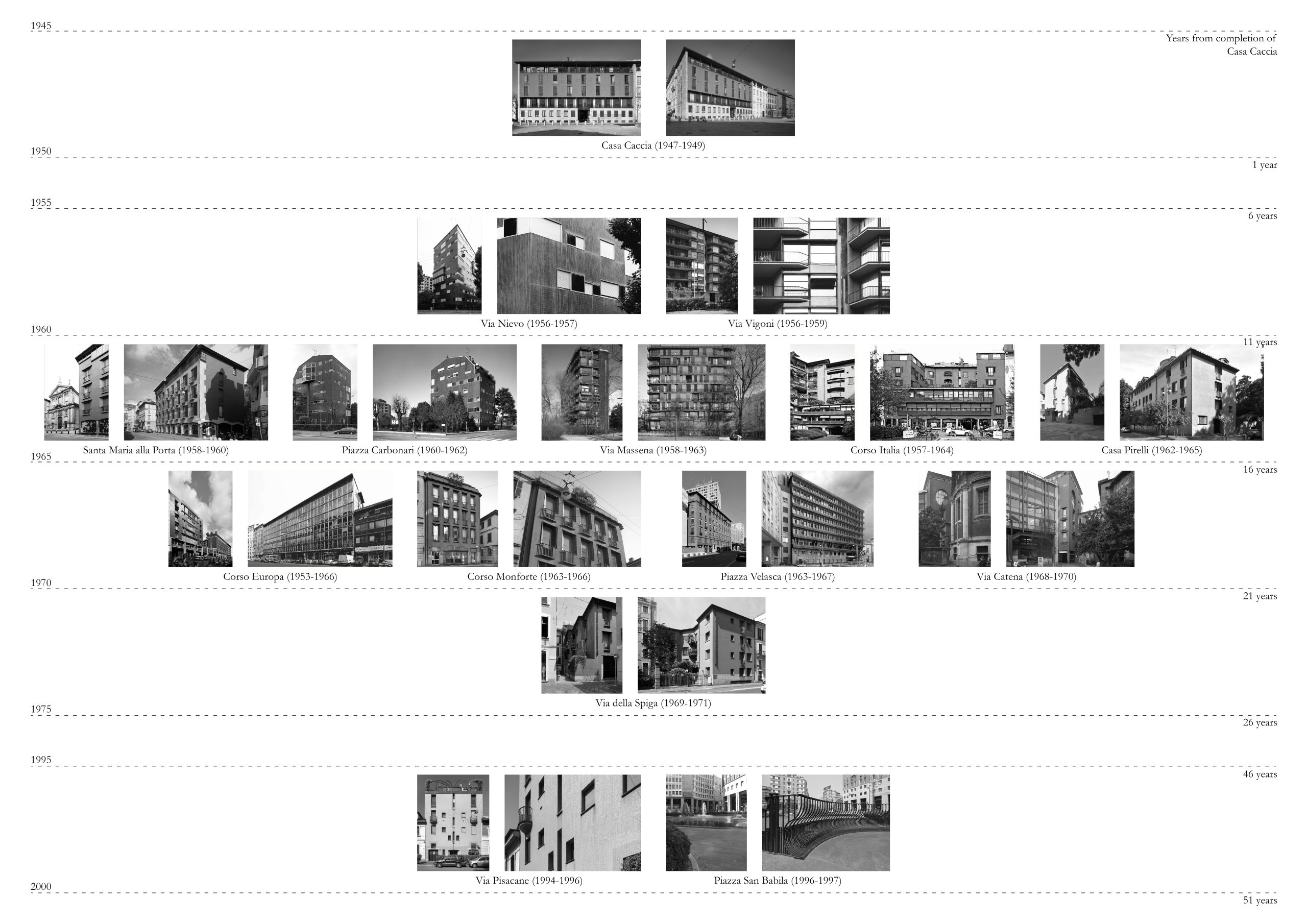

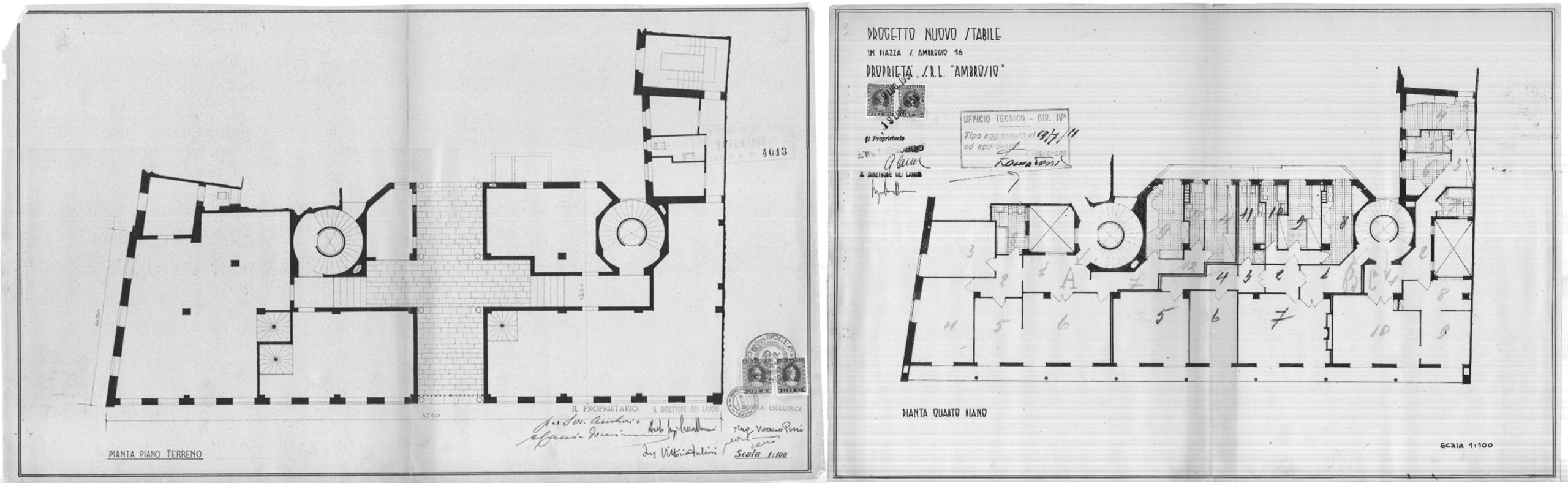

Figure 20 – Timeline of Casa Caccia, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi) (Photo credits in note [7])

To reach the most refined version of their opus, all professionals experience formative years. They test, try, and sometimes fail, in order to reach an expressive form that resonates with them. All the traits that will define Caccia’s work are already present in the house in Sant’Ambrogio, though yet unpolished. Different references and signs appear condensed, displayed together in plan and on the façade. Casa Caccia is not only the manifesto for modern restoration indicated by Pica, but it also establishes the rules of Caccia’s architecture. Looking at postwar production in Milan, we have to remember that even though these were the first built works of will-be household names, all these architects were not fresh out of university, nor totally new to the design scene. Those formative years I referred to before were hindered by the war, as construction was not possible, yet those were not wasted times. As Professor Pierini usefully pointed out, they served for what was to come (PIERINI, 2025). Regardless of the fact that Caccia was not building, he was still producing and had the time to reflect and work theoretically on his architecture. Thus, when it came to actually constructing, he had already developed a number of pretty solid ideas of what their architecture would be, hence explaining the richness of the Casa Caccia project. This building stands out not as a singularity as much as a catalyst. It can almost be read as a map of his following production, planting the seeds and clearing the path for the typological freedom Caccia will be able to achieve in the following ten to thirty years.

Figure 21 – Abacus of Façades, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi) (Photo credits in note [8])

The resurgence of the façade (see Abacus of Façades, Figure 21)

Shielding its interiors from the public eye in true Milanese fashion, in Palazzo Caccia, Caccia Dominioni creates a combined façade (Figure 22). The main elevation is sandwiched between two lateral planes of beola gneiss, punctuated by evenly distributed windows on Via San Vittore, echoing the neighbouring building and showing Caccia’s contextual approach. The regularity of the openings is abandoned on the main front, where he no longer responds to the neighbouring edifice. He applies the same logic in the Corso Monforte building (1963-1966), where Caccia maintains a rhythmic and regular distribution of windows on the main front but not on the one on Vicolo Rasini. The five storeys fronting the square pull apart, generating spatial depth and surface movement. The loggias will come back in later works, on the last floor of the Piazza Velasca building (1963-1967) or in the glazed upper level of Santa Maria alla Porta (1958-1960). Still, the most sophisticated and expressive evolution of the impression of movement he achieves on the façade is to be found in Via Vigoni (1956-1959), where the entire front is comprised of balconies and recessions pulling in and out, shifting to convey movement. The bottom floors are clad in Ceppo stone from Camerata Cornello, producing the impression of a plinth, much like he does in Piazza Velasca. Clay-coloured plaster coats the second and third, echoing Pompeian red. Earth-toned “Terra di Siena” hues are paired with large timber shutters on the recessed levels. In Via Massena (1958-1963), he will reprise this system of timber shutters, turning it into the defining element of the building’s external envelope. Overall, Caccia always uses hearty and natural tones, as he doesn’t like to add colour that doesn’t exist. Even in the case of Via Nievo (1956-1957), which apparently seems an exception to this rule, he claims that the blue tiles relate to the sky (SACERDOTI and CIGARINI, 2005).

Figure 22 – Casa Caccia, Front Elevation, 1947 (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/?offset=1 [Acc. 15/07/2025])

The altered rhythm of the windows and the deliberate asymmetry create a façade that is at the same time classic and innovative. The buildings in Piazza Carbonari (1960-1962) and Via Nievo are an extreme manifestation of this process of distillation of elements, where any formal attempt at ordering the windows on the façade is deliberately abandoned in favour of their performative role within the layout. On the overall abstract base of the facade, the decorative iron handrails, different at each level, create interest and add an almost narrative depth, unlocking memories. On the second and third floors, those same balustrades bear the initials of Caccia’s parents in an ornamental fashion that demonstrates his willingness to maintain an individual approach regardless of prevailing trends (Figure 23). Caccia is not afraid of adding decorative details, which still maintain a modern character thanks to the combination with the more rationalist elements of the façade. Mosayebi explains the reasons behind this recurring strategy, she claims “the emphasis is not on seeking topicality and modernity in expression, but rather on creating continuity with the tried and tested and familiar through a formal reference to a familiar object.” (MOSAYEBI, 2014: 83). Caccia will maintain this position all thorough his life, not shying away from ornaments as demonstrated by the decorative curve of the San Babila fountain (1996-1997), the pattern on the balustrades of the Via-Pantano-facing balconies of the Piazza Velasca building, the iron pergola resting atop the terrace in Via Pisacane (1994-1996) or the undeniably decorative character of the elliptical window that looks at the apse of the church of San Fedele from the façade of the house in Via Catena (1968-1970).

Figure 23 – Piazza Carbonari, 2013 (Source: Giorgio Casali. Werk, bauen + wohnen, 12. Verlag Werk AG)

Combining languages and temporality in one building, the Caccia Dominioni of the house in Sant’Ambrogio is still architecturally immature: his language is still green. Nonetheless, he already displays what Pierini, in conversation, calls an “innate naturalness to architecture” and a sophisticated interiorisation of history and its systems. (PIERINI, 2025) Of the building, Irace says that Caccia combines restoration with invention, constructing a tradition that is “interiorised and recognisable as the expression of a local identity.” (IRACE, 2002: 17) Here, the façade regains its identity as an architecturally independent element; it is no longer only an expression of the built form but becomes again a vessel of messages and statements. According to Mosayebi, “what is expressed in the new and more specific design of the façades is a re-evaluation: the identity of the owners, their participation in public life, but also their long history and their claim to a high status within society should be recognisable.” (MOSAYEBI, 2014: 91). It responds to local codes and moves away from the anti-decorative pragmatism of European modernism, establishing ‘a Milanese way’ that responds to the city’s codes and reflects its traditions.

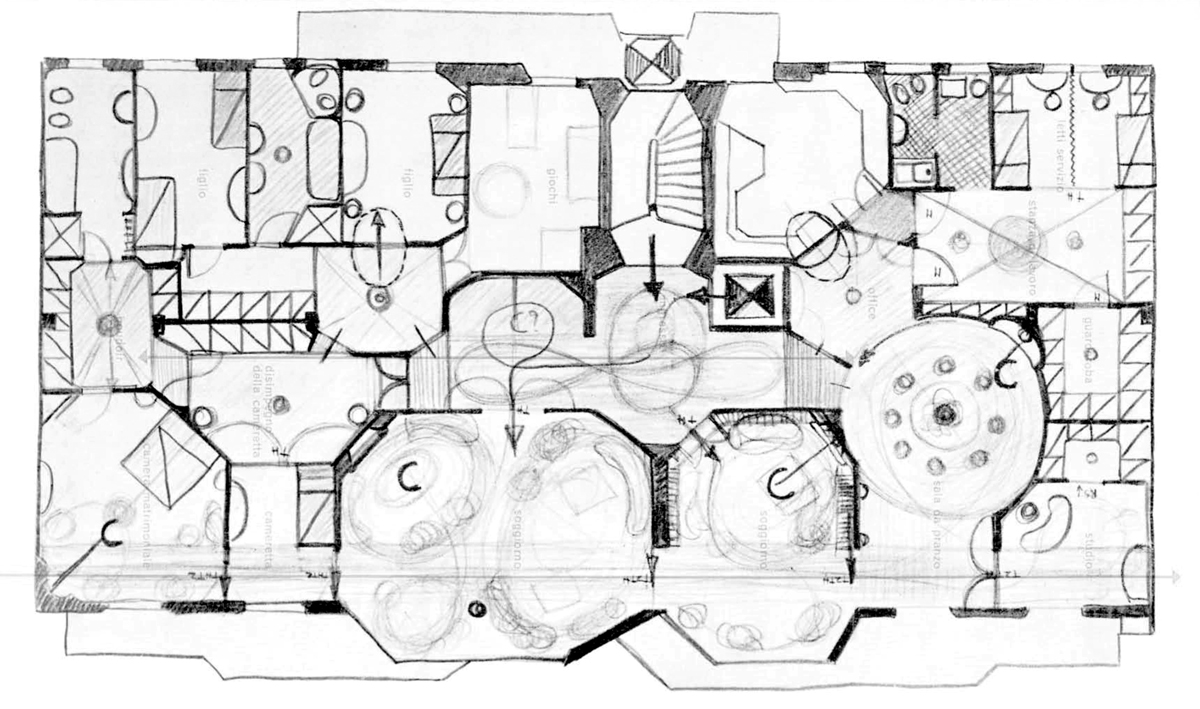

Figure 24 – Abacus of Plans, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi) (Drawings credits in note [9])

The apartment as a micro-city (see Abacus of Plans, Figure 24)

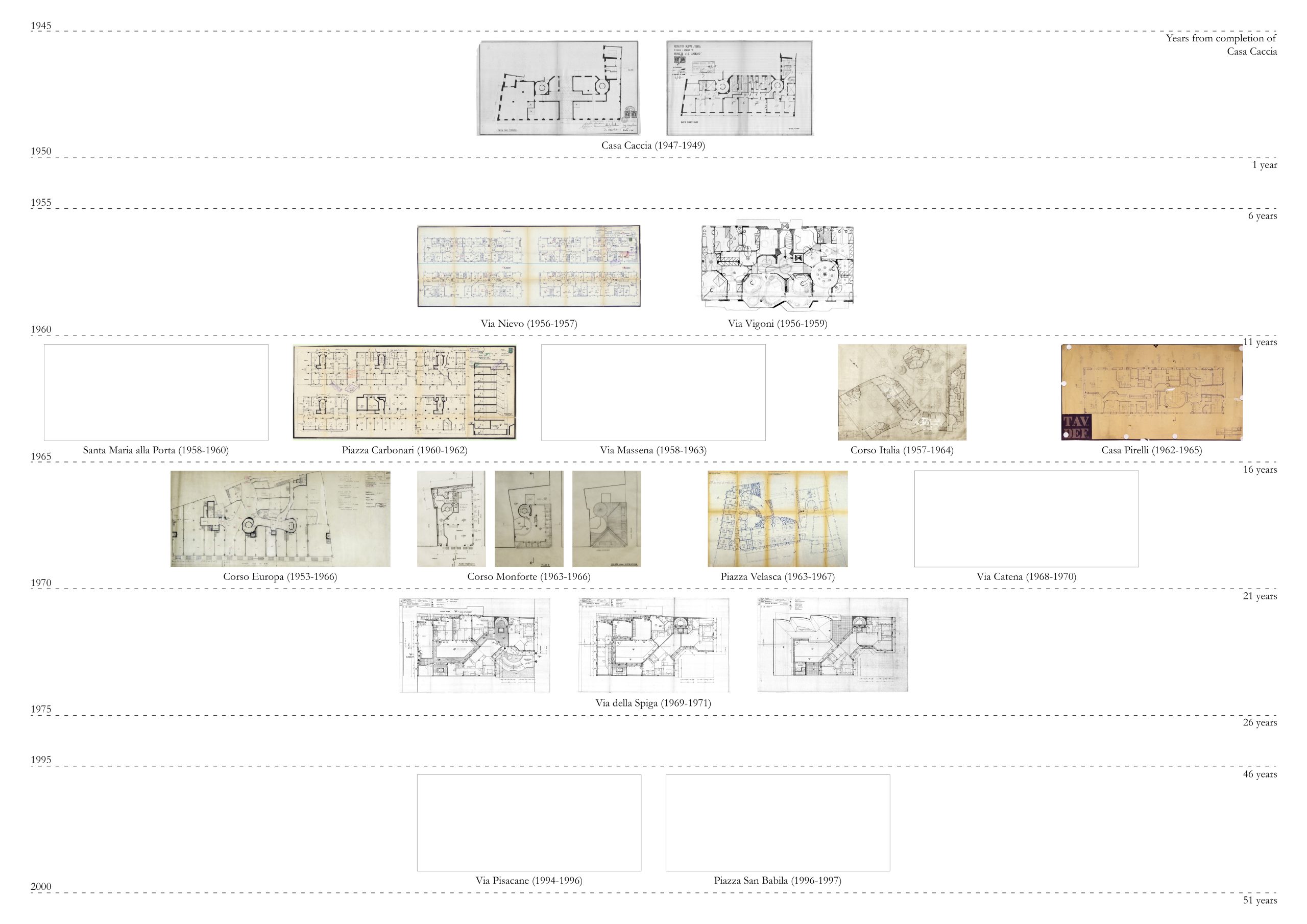

As it is typical of Milan’s tendency to hide behind its monumental façades, the layout and interior character can only be discovered by crossing the threshold (Figure 25 and 26). Emphasised by Caccia’s shift of the main entrance, sitting asymmetrically in the façade, the act of entering the building gains new importance. Two iron dog statues, positioned facing each other, guard the twin landings leading, with their decorative mosaic flooring, to the helicoidal stairs and lifts to the upper levels (Figures 27, 28 and 29). Mosaics will become a distinctive element of Caccia’s buildings through his lifelong collaboration with artist Francesco Somaini, notably the author of the ones in the TiKiVi project in Corso Italia (1957-1961), presented by Zucchi at the Biennale (ZUCCHI, 2018: 113-121). The entrance irregularity and the baroque character of the circulation system make up the type of delicate, unpredictable moments that are so dear to Caccia and will come to distinguish his architecture, especially in the layout and organisation of the plan. The same surprise effect is achieved by the odd window placement on the façade in Corso Italia and the mismatched, irregular helices of the stairs in Corso Europa (1953-1966). In later times, talking about his work, Caccia will describe himself as a “piantista,” a designer who lives and dies on the plan (SACERDOTI; CIGARINI, 2005). Looking at the layout of Casa Caccia, it is clear that he is not there yet, but the foundations of that approach to the house as a “micro-city” are being laid. (GIZMO, 2016) I would assume he was not yet self-assured enough to present the level of baroque that defines his later plans. He is not shaping the rooms into ambiences yet, nor pushing as far as to design the way the user would live inside the building, as happens ten years later in Via Vigoni. Here, even the way the plan is sketched gives the impression of a heavily detailed program imagined for all the presented spaces (Figure 30). In Casa Caccia, instead, he sticks to traditional space division, dictated by convention, saving his tweaks for specific moments, all of them secondary in the hierarchy of spaces. Service areas are at the back, circulation is situated in the middle, while the bigger rooms are at the front and look out into the square, as typical of aristocratic palaces.

Figure 25 – Ground Floor Plan, Casa Caccia, 1947 (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/?offset=1 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Figure 26 – Fourth Floor Plan, Casa Caccia, 1947 (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/?offset=1 [Acc. 15/07/2025]).

Observing the plan in talk with Professor Pierini, she pointed out how it is in the circulation areas that Caccia Dominioni’s genius architectural sensibility and innovations start to emerge (PIERINI, 2025). It is not a case that he started experimenting with these parts of the building –staircases, corridors, and elevators– as it would be less of a shock and easier to accept within those architectural rules he was moving within. Caccia embraces the “exception,” the unexpected twist, that characterises aristocratic architecture and translates it to residential housing. The corridor presents an initial expression of that compression and depression of spaces that we find in the plans of the architect’s later works. The stairs ascend in a helicoidal turn that wraps around the lifts. This specific conformation is one he seems to appreciate; he reprises it in Via Nievo and in an extreme expression in Corso Europa, where the helix is compressed into forming an elliptical plan. Irace, too, claims that Caccia is reforming the house from his lower elements – staircases, corridors, and elevators (IRACE, 2002: 25). Later on, more accomplished and conscious of his capabilities, he will not fear to tackle the whole plan, shaping the rooms into environments. Within the boundaries of the residential project, he will be able to achieve effects, movements, and variations proper to the city-scale. Caccia Dominioni refuses the free plan and favours unbalanced layouts, also highlighting the high-end nature of his commission and clients. His designs demonstrate a disregard for modularity and a penchant for the unexpected, creating ambiences and micro cities.

Figure 27 – The entrance of Casa Caccia, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi) Figure 28 – Staircase landing, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi) Figure 29 – Staircase detail, 2025 (Source: Rebecca Billi)

III Caccia’s architectural expression

A baroque urbanist and an architectural dandy

Paraphrasing Christopher Alexander, a building is not a tree, and architectural history and composition do not develop – ramify – in a foreseeable and hierarchical way (ALEXANDER, 1965). It is instead made of different moments of encounters amongst its players and influences. They meet and build upon or in opposition to each other. Casa Caccia is a physical manifestation of this tendency, of how, when successful, one architecture can become bearer and herald of its history and of its present. Caccia made use of a concept of tradition that is not afraid of history nor ornaments, recognising communicative strength in both. His focus goes against what will become known as La Tendenza, the leftist discourse that reigned in the city’s theoretical scene and the spaces of the Politecnico with its social call and political character. [5] He belonged to a different Milan, an aristocratic Milan, where ornaments and decoration held meaning as memorabilia of a shared, continuous story. To Caccia, memory was tangible and objective; it was not theoretical. Referring to Mosayebi, she relates this to his “eclectic attitude,” one that brings together past and present without fusing them into a unity but rather recognising their individuality (MOSAYEBI, 2014: 91), Through his technical knowledge and implicit consciousness of tradition and architectural history, Caccia is able to realise not only buildings but “urban figures,” as Pierini calls them (PIERINI, 2025).

Pierini also defines him a “baroque urbanist” due to the capability he has to create excitement and surprise within the boundaries of the plan (PIERINI; ISASTIA, 2017: 39). Inside homes, he makes squares and churches, and he does this by keeping to the domestic dimension. Cino Zucchi, on the other hand, refers to him as an “architectural dandy.” (ZUCCHI, 2025). His strength lies in the knowledge of those conventions he has appropriated. He moves through them at ease, with a sense of belonging that allows him to break away in order to let his individuality emerge. Having made all the rules his own, any form of sprezzatura he displays does not denote carelessness as much as intention. [6] It is a skill that comes from deep knowledge and understanding, the same one that characterises the aforementioned dandy. Caccia is not an outcast, recounts Zucchi, and he is not a rebel shouting on the street to make himself heard. He knows the codes of Milanese architecture and society, and how to tweak them. He will break away from them clearly, but in an appropriate form. Said slight twists, recurring throughout his production, inform a sequence of works that make an architecture based on typological expressive freedom. This started in Sant’Ambrogio. Caccia approached the reconstruction of the family palace like a dandy who would not wear sandals with a suit but might add a pink sock, clearly visible between the correct trousers’ hem and the proper shoes. (ZUCCHI, 2025).

Figure 30 – Via Vigoni 13, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://living.corriere.it/architettura/gallery/storie-di-case-milanesi-villa-necchi-campiglio/?pag=2 [Acc. 15/07/2025])

Conclusion

The city, the palace, and Caccia’s legacy

The image of the city of Milan, hence, is not given by the Duomo nor by the city’s many churches. Rather, it is to be found in the eclectic collection of residential buildings realised by an enlightened group of architects that, in the 20th century, were able to read and understand the hue and singularity of the time, and the social identity of Milan as an urban centre and modern capital. In Sant’Ambrogio, we find an architecturally immature Caccia. While experimenting with that collection of signs and codes that will later define his production, the references appear to be almost too blatant, too explicit – they lack the subtlety of contextual hints he is famous for. Yet the core of Caccia’s approach to history and building is already present; he’s working towards its more polished version using his own house as a testing ground. While Ruskin preserved the ruin and Le Duc rebuilt the building, in Caccia’s Milan, history was dealt with through continuity and criticism. In Casa Caccia, the architect reads the traces of the past and uses them to inform a contemporary language that maintains its relevance. While being a product of its own time, it maintains its significance for later audiences, able to understand and pick up on his collection of signs. A significance that could be compelling to further investigate by looking at the influence Caccia’s work exercised on later Milanese production, as well as –maybe more interestingly– on contemporary architecture practices, especially in nearby Switzerland. Caccia interiorised the “hue of the past” to the point he could reference it without copying, revisit without recreating it, following that “Italian way” so dear to Gio Ponti. It is in the praxis of architects that Italian production presents itself as a continuum rather than through unrelated trends. Casa Caccia exemplifies a nuanced approach to architecture that nonetheless works both as a manifesto for postwar architecture and a platform for personal experimentation, weaving between tradition, tangible memory, and innovation. Caccia refuses temporary fashions and recreates the ambience of Sant’Ambrogio. The building reflects a conscious response to its environment and an effort to reconcile modern architectural expressions with a praxis-based perception of “tradition.” It is a vessel of cultural memory and a testament to Milan’s resilience as a city. Above all, it shows that modernity doesn’t need to reject the past, but can build upon it in continuity.

Bibliography

ALEXANDER, Christopher – A City is Not a Tree. Berkeley: Center for Environmental Structure, 1965.

ACERBONI, Francesca – Cino Zucchi and the Everyday Wonders of Caccia Dominioni. Domus. June 28, 2018. Available at: https://www.domusweb.it/it/speciali/biennale/2018/cino-zucchi-e-le-meraviglie-quotidiane-di-caccia-dominioni-.html [Accessedon 28 March 2025].

ALBEROLA PEIRÓ, Mónica - Luigi Caccia Dominioni: Ejercicios de estilo. Madrid: Ediciones Asimétricas, 2023.

ALBEROLA PEIRÓ, Mónica – Luigi Caccia Dominioni (1913–2016). The Case of Vigoni. A Voyeur in View. Constelaciones, n.º 6, 2018, p. 147–160. Available at: https://oa.upm.es/87418/1/9895702.pdf [Accessed 17 June 2025].

ARIELLI, Emanuele – Stile e stili di pensiero. In: FRANZINI, Elio; UGO, Vittorio (Eds.) – Stile. Milano: Guerini e Associati, 1997, p. 21-40. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/11578/48319

BANHAM, Reyner – Neoliberty: The Italian Retreat from Modern Architecture. The Architectural Review, n.º 747, April 1959, p. 231-235.

BIRAGHI, Marco – Il secolo lungo di Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Gizmo, n.º 9, Dicembre 2013. Available at: https://www.gizmoweb.org/2013/12/il-secolo-lungo-di-luigi-caccia-dominioni/. [Accessed on 25 March 2025].

– Casa Caccia Dominioni – Milano (MI). Architecture in Lombardy from 1945 to Today. Lombardia Beni Culturali. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/. [Accessed on 28 March 2025].

FERRARI, Veronica – L’incontro tra architettura e arte: Luigi Caccia Dominioni e Francesco Somaini. Studi e ricerche di storia dell’architettura, n.º 1 (2020), p. 14–27. Milan: Politecnico di Milano. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.17401/studiericerche.8.2020-ferrari. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/11311/1170133. [Accessed 17 June 2025].

FINOCCHI GHERSI, Lorenzo – Luigi Caccia Dominioni Architetto nella Milano del Dopoguerra. In: GIOVANNETTI, Paolo; MORETTI, Simona (eds.) – Milano tra memoria e ricordo, identità e immaginario, distruzione e ricostruzione. Milan: Mimesis, 2022, p. 63-78.

IRACE, Fulvio; MARINI, Paola (eds.) – Luigi Caccia Dominioni: stile di Caccia: case e cose da abitare. Venezia: Marsilio, 2002.

LEVATI, Stefano – La Milano di Stendhal. Revue Stendhal, n.º 2, 2021, published on 1 January 2024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/stendhal.422. Available at: http://journals.openedition.org/stendhal/422. [Accessed 9 June 2025].

– Lo ‘stile’ Caccia Dominioni in mostra a Verona. Domus. January 30, 2003. Available at: https://www.domusweb.it/it/architettura/2003/01/30/lo-stile-caccia-dominioni-in-mostra-a-verona.html. [Accessed on 27 March 2025].

LUCCHINI, Marco – Luigi Caccia Dominioni: Refinement and More is Less. In: LUCCHINI, Marco; BONENBERG, Agata (eds.) – Architecture Context Responsibility. Establishing a Dialogue and Following Patterns. Milano: Politecnico di Milano / Poznan: Poznan University of Technology, 2015, p. 5-17.

– Luigi Caccia Dominioni (1913-2016). Gizmo, n.º 13 novembre 2016. Available at: https://www.gizmoweb.org/2016/11/luigi-caccia-dominioni-1913-2016/. [Accessed on 25 March 2025].

LUMLEY, Robert; FOOT, John (eds.) – Le città visibili: spazi urbani in Italia, culture e trasformazioni dal dopoguerra a oggi. Milan: Il Saggiatore, 2007.

MOSAYEBI, Elli – Konstruktionen von Ambiente: Wohnungsbau von Luigi Caccia Dominioni in Mailand, 1945–1970. Doctoral dissertation, ETH Zurich. ETH Zurich Research Collection, 2014. Available at: https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/96767

ORDINE DEGLI ARCHITETTI PPC DI SONDRIO – Press release for the exhibition “Architetture di Luigi Caccia Dominioni”. Curated by Alberto Gavazzi and Marco Ghilotti. Palazzo Lambertenghi, November 28 – December 14, 2014. Available at: https://www.ordinearchitettisondrio.it/images/pdf/articoli/CARTELLA_STAMPA.pdf [Accessed on 28 March 2025].

PERTOT, Gianfranco; RAMELLA, Roberta (eds.) – Milano 1946: Alle origini della ricostruzione. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2016.

PIERINI, Orsina Simona; ISASTIA, Alessandro – Case milanesi 1923-1973: cinquant’anni di architettura residenziale a Milano. Milano: Hoepli Editore, 2017.

POLIN, Giacomo – Un architetto milanese tra regionalismo e sperimentazione: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Casabella n.º 508, December 1984, p. 42.

PONTI, Gio – Amate l’architettura. Milan: Rizzoli, 1957.

SACERDOTI, Pierfrancesco; CIGARINI, Tommaso – Interview with Luigi Caccia Dominioni, 2005. In: D’AGOSTINO, Salvatore – 0056 [SPECULAZIONE] Buon compleanno Caccia! Wilfing Architettura. December 2016. Available at: https://wilfingarchitettura.blogspot.com/2016/12/buon-compleanno-caccia.html. [Accessed on 3 April 2025].

SAVORRA, Massimiliano – Architetture di Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Il “decoro” dell’architettura milanese. Architettura Civile, n.º 9/10, 2014. Araba Fenice, p. 2-4.

STENDHAL – Il laboratorio di sé. Corrispondenza, vol. III (1813–1821). Turin: Aragno, 2016.

STENDHAL – Rome, Naples, and Florence (1816). London: John Calder Publishers, 1920.

TORRICELLI, Angelo – Architetture di Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Autenticità e Misura. Architettura Civile, n.º 9/10, 2014. Araba Fenice, p. 1.

– Visita guidata speciale case. Ordine degli Architetti di Milano [19.02.2025]. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/en/eventi/visita-guidata-speciale-case. [Accessed on 27 March 2025]

ZUCCHI, Cino; BASSOLI, Nina (eds.) – Innesti/Grafting. Vol. 2: Milano. Laboratorio del moderno. Veneza: Marsilio Editori, 2014.

ZUCCHI, Cino; PIERINI, Orsina Simona (eds.) – Everyday Wonders / Meraviglie Quotidiane. Luigi Caccia Dominioni and Milano: The Corso Italia Complex. Mantova: Corraini Edizioni, 2018.

Notes

[1] Sciura is a word from the Lombard dialect, literally meaning ‘lady.’ From the economic boom onwards, especially in Milan, it has come to indicate a woman living in the city centre and belonging to the upper class. She is generally elderly, immaculately groomed, and sports an elegant and refined style.

[2] Relevant doctoral research on Caccia Dominioni includes the following theses:

Konstruction von Ambiente – Wohnungsbau von Luigi Caccia Dominioni in Mailand 1945–1970, Elli Mosayeby, ETH Zurich, 2014; Compositional Studies on Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Veronica Ferrari, Politecnico di Milano, 2020; Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Ejercicios de estilo, Monica Alberola Peirò, Universidad Técnica de Madrid, 2021.

[3] In addition to the ones cited, the exhibitions that stand out are Architetture in Valtellina e nei Grigioni (2010, Morbegno, Gavazzi and Ghilotti); Architetture di Luigi Caccia Dominioni (2014, Sondrio, Gavazzi and Ghilotti with PoliMi); Nelle Case (2024–25, Villa Necchi, Milan; Pierini and Morteo).

[4] A good example of this strategy is the Condominio XXI Aprile, located on Via Lanzone n 4, and completed by Asnago & Vender between 1950 and 1953. See also ORDINE DEGLI ARCHITETTI DI MILANO. Condominio XXI Aprile – Asnago e Vender. Itinerari di Architettura, 2024. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/44-asnago-e-vender/opere/454-condominio-xxi-aprile.

[5] La Tendenza was an Italian architectural movement reacting to post-war Modernism. The movement rejected utopia in favour of a political and critical architecture with a firm grip on reality. Emerging in the 1960s and anticipating Postmodernism, it emphasised debate through journals and architectural critique, particularly by figures like Manfredo Tafuri. Mario Ridolfi, Alessandro Anselmi, Carlo Aymonino, Paolo Portoghesi, Ernesto N. Rogers, Aldo Rossi, and Massimo Scolari were all part of this movement. (PASSI, Dario. La Tendenza. Available at: http://www.dariopassi.com/assets/20120611_dp_tendenza_ang.pdf).

[6] I refer to sprezzatura according to the acception that came to define mannerism and baroque times, as a disdain for rules as a sign of virtuosity rather than ignorance.

[7] Casa Caccia Dominioni, 1920 (Source: Unknown Author. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/MilanoScomparsa [Acc. 01/07/2025]). Casa Caccia Dominioni after the bombing, 1943 (Source: Unknown Author. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/MilanoScomparsa [Acc. 01/07/2025]). Casa Caccia undergoing construction, 1952 (Source: Archivio Civico di Milano. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture/schede/3m080-00050/ [Acc. 11/07/2025]) Casa Caccia Dominioni, 2015 (Source: Marco Introini. Available at https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/ [Acc. 01/07/2025])

[8] Casa Caccia Dominioni, 2015 (Source: Marco Introini. Available at https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/ [Acc. 01/07/2025]) Via Ippolito Nievo 28/a, 2013 (Source: Vincenzo Martegani. Available at https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00174/ [Acc. 11/07/2025]) Via Vigoni, 2013 (Source: Vincenzo Martegani. Available at https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00173/?offset=14 [Acc. 11/07/2025]) Via Santa Maria alla Porta 11, s.d. (Source: Vincenzo Martegani. Available at https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/526-edificio-per-uffici-e-negozi/galleria [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Via Santa Maria alla Porta 11, 2013 (Source: Mattia Morandi. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/526-edificio-per-uffici-e-negozi/galleria re.public.polimi.it [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Piazza Carbonari 2, 2008 (Source: Marco Introini. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00176/ [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Via Andrea Massena 18, 2015 (Source: Marco Introini. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00175/ [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Corso Italia 22, 2015 (Source: Marco Introini. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00174/ [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Corso Italia 22, 2013 (Source: Vincenzo Martegani. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00174/ [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Via Cavalieri del Santo Sepolcro, 2010 (Stefano Suriano. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00017/?offset=13 [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Corso Europa 11, 2016 (Source: Stefano Suriano. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00254/ [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Corso Europa 10, 2013 (Source: Vincenzo Martegani. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00194/ [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Corso Monforte, 2012 (Source: Fabrizio Arosio. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/495-edificio-per-abitazioni-e-negozi/galleria [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Edificio per uffici Cartiere Ambrogio Binda & Vip’s Residence, s.d. (Source: Stefano Suriano. Available at: https://censimentoarchitetturecontemporanee.cultura.gov.it/scheda-opera?id=2504 [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Via Catena 15, 2015 (Source: Marco Introini. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00227/?offset=19 [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Complesso Residenziale Via Santo Spirito / Via della Chiusa, 2016 (Source: Stefano Suriano. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00019/?offset=20 [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Complesso Residenziale Via Santo Spirito / Via della Chiusa, 2016 (Source: Alessandro Sartori. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00019/?offset=20 [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Via Pisacane 25, 2015 (Source: Marco Introini. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00271/?offset=26 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Piazza San Babila Balustrade, s.d. (Source: Vincenzo Martegani. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/694-piazza-san-babila/galleria [Acc. 14/07/2025]) Piazza San Babila, s.d. (Source: Valeria Fermi. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/694-piazza-san-babila/galleria [Acc. 14/07/2025])

[9] Ground Floor Plan, Casa Caccia, 1947 (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/?offset=1 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Fourth Floor Plan, Casa Caccia, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00171/?offset=1 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Second, third, fourth, and fifth floor plans, Via Nievo, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00172/?offset=3 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Via Vigoni 13, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://living.corriere.it/architettura/gallery/storie-di-case-milanesi-villa-necchi-campiglio/?pag=2 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Floor Plans and Cross Section, Piazza Carbonari 2. s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/p4010-00176/?offset=7 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Fourth Floor, Corso Italia Complex, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/518-edificio-per-abitazioni-uffici-e-negozi/galleria# [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Ground Floor Plan, Via Cavalieri del Santo Sepolcro, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00017/?offset=13 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Ground Floor Study, Corso Europa, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/470-complessi-per-uffici-negozi-e-abitazioni/galleria [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Ground Floor Plan, Corso Monforte, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/495-edificio-per-abitazioni-e-negozi/galleria [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Fourth Floor Plan, Corso Monforte, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/495-edificio-per-abitazioni-e-negozi/galleria [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Rooftop Plan, Corso Monforte, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/cultura/itinerari-di-architettura/45-luigi-caccia-dominioni/opere/495-edificio-per-abitazioni-e-negozi/galleria [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Floor Plan, Cartiere Ambrogio Binda & Vip’s Residence, Piazza Velasca, s.d. (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00018/?offset=18 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Elevated Ground Floor, Via della Spiga, 1968 (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00019/?offset=20 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) First Floor Plan, Via della Spiga, 1968 (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00019/?offset=20 [Acc. 15/07/2025]) Rooftop Plan, Via della Spiga, 1968 (Source: Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Available at: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture900/schede/RL560-00019/?offset=20 [Acc. 15/07/2025]).