Karolyna de Paula Koppke

karolyna.koppke@fau.ufrj.br

PhD student of the Graduate Program in Architecture at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (PROARQ/UFRJ). Assistant Professor of Architecture and Urbanism course at Ibmec RJ, Brazil.

To cite this paper: KOPPKE, Karolyna de Paula– For a historiography of displacements: Analysing the nineteenth century in Europe and America. Estudo Prévio 23. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2023, p. 63-79. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/22.6

Paper received on 30 August 2023 and accepted for publication on 15 September 2023.

Creative Commons, license CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

For a historiography of displacements: Analysing the nineteenth century in Europe and America

Abstract

This work intends to consider displacements between geographical borders as an axis for writing a history of art and architecture in Europe and America. It takes as its basis an excerpt from the biography of Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre (1806-1879) and his formative trip to Italy. In doing so, it places at the centre of the analysis the intellectual production of an actor who, already in the 19th century, made efforts to build a common – but not homogeneous – culture based on the two-way crossing of the Atlantic. We understand that paying attention to these geographical dispositions helps us understand displacements of a different order – now, historiographical – that were understood early on for building a history of art and architecture specific to the developing Brazilian nation.

Keywords: Historiography of art and architecture in Brazil; Displacements; Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre; Grand Tour; Archaeology.

Introduction

In the paper Araújo Pôrto-Alegre, precursor dos estudos de história da arte no Brasil, published in 1944 in Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rodrigo Mello Franco de Andrade (1898-1969) describes the 19th-century artist and man of letters as a “venerated patron” (p. 131) of the newly established national heritage protection authority. A close correlation between modernity and history was established in the daily work of the old National Historical and Artistic Heritage Service (SPHAN), founded in 1937. But not just any type of history. Those intellectuals who, in the 1930s, took for themselves the task of preserving examples of Brazilian culture they considered genuine chose to build a narrative guided by a logic capable of situating and justifying actions in the present, driven, in turn, in the direction of a shared project in the future. Rejecting 19th-century cultural production and classifying it as foreign was part of the strategy of building this narrative. Considering this, it is interesting that Rodrigo Mello Franco appointed Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre (1806-1879) to the most critical position at SPHAN.

Here, we will consider the biography of Porto-Alegre, a multifaceted man who was a designer, landscape painter, critic, and art historian. His trajectory – especially the period he spent in Italy and the archaeology classes he attended there – has proved beneficial to understand the centrality, already in the nineteenth century, of the exchanges established from the multiple Atlantic crossings in the 1900s, at the time undertaken in different conditions and senses. A new era was arising. An era that required new tools, for whose construction Porto-Alegre actively contributed. Trade through the Atlantic will gradually allow for a common culture to be formed, not imposed or uniform, but – and that is key – shared. This is why displacement is interesting. Initially, geographical displacement. At a later stage, subjective displacement is relevant, resulting from a new perception of the other, especially the self. We propose a historiographical practice that deviates from the perception of geopolitical boundaries as crystallised instances and avoids the aprioristic and dichotomic position the approach leads to. By focusing on mobility and the short lifetime, the text suggests reflection on the possibilities of writing history that, without neglecting asymmetries, does not establish them as a starting point. Porto-Alegre and his contemporaries could think and move beyond (political, economic, and social) borders that guided the rhythms of their time.

Between the subject and the structures: A historiographical change

For much of the 20th century, comparative history was the approach par excellence to thinking to writing a history of Latin America. Two paths were traditionally used. The choice and interpretation of the phenomena was based on the comparison between nations of the subcontinent itself or – even a more common option – between Latin American and European countries. The latter usually resulted in an established narrative as “a one-way route”.

Established in the late 1920s[1], the comparison became an object of criticism in the 1970s, when historiographic practices took new directions, leveraged by the intellectual triumph of fields such as linguistics, sociology or anthropology, which now threatened the relevance given to the study of economic or demographic contexts and the social structures that marked historiography based on national borders. Gradually, a defence arose of object-based rather than structure-based research. Roger Chartier, for example, in his Text O mundo como representação (1991), will recall that such structures, as well as their practices, are produced precisely by contradictory and confrontational representations designed by individuals and groups to give meaning to their world.

The edition of Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, November-December 1989, entitled Histoire et sciences sociales. Un tournant critique?, in which Chartier’s text is published, marks, in fact, a pivotal moment for the redefinition of the agenda for historical research in France. In this edition, François Dosse (2010) will comment that engagement in a new direction, based on attention to the actors, results in a reconfiguration of time, from the revaluation of the short term, the action situated, the action in context. According to the author, this awareness of historicity would lead to two perspectives. The first concerns understanding the historicity of the studied societies, which unfolds in the strength of singular phenomena and, consequently, in a historiographical practice, attentive to events or biographies. The second refers to the historian’s understanding of his time, incurring a departure from the ingenuity inherent in the idea that he speaks about reality.

At the same time, in France, proposals by Italian micro-historians were also being disseminated, for which the work undertaken by Jacques Revel was essential. In Jogos de escalas: a experiência da microanálise, published in 1996, Revel starts by stating that the problem of coordinating singular experience and collective action, i.e., the subject and the structures, is still unresolved. By describing the mechanisms employed by the fans of micro-history, he informs his reader that they practice a multiple contextualisation work, which he names the “game of scales”. He recalls that historical actors participate in processes in contexts of varying dimensions and levels and, in this sense, there is no gap or opposition between local and global history. The approach to the experience of an individual, for example, would allow us to perceive a particular modulation of global history, thus being another way of mapping social and cultural dimensions. This conception of the problem would allow for seeing it in terms of strength/weakness, authority/resistance, and centre/periphery, shifting the analysis to circulation, negotiation and appropriation at all levels. The intention is to show how faced with chaos, social actors invent a sense that they simultaneously become aware of.

Gradually, the path will be open for Chartier to publish, in the early 2000s, his book urging global history. An entire issue of Annales will focus on the subject, evoking proposals dealing with connection and circulation, approaches that are established as criticism to comparison. Rejecting the preference for any scale of work and recovering basic concepts of his profession as a historian and adding others to them, Chartier invites readers to reflect on:

“L’histoire des connected histories ne peut donc éviter une réflexion rigoreuse sur les catégories d’analysis les plus adéquates a son projet. Comment penser la relation entre appropriation et acculturation, entre réemplois inventifs et arrachements culturels? Comment caracteriser les processus d’«interaction’ ou de «negociation’ (Terme cher, a la fois, a la microhistoire du monde social et a la critique littéraire new historicisť) selon qu’ils opèrent a l’interieur de relations de domination ou dans des rapports d’échange? Ou encore, comment situer les métissages culturrets entre colonization et globalization des imaginaires?”[2] (CHARTIER, 2001: 123, in italics in the original)

This is how, considering Araujo Porto-Alegre, a man who wanted to be global in the 19th century, we will try to write history that focuses on mobility and crossing borders. We will study America and Europe – Brazil and Italy, more precisely – not as homogeneous and abstract entities, the latter being the educator of the former. This man’s history, interspersed in the conditions that marked it, will give origin to a more complex narrative.

Young Porto-Alegre and his Formative Trip

On July 25, 1831, at 24 years old, the young Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre (1806- 1879), together with his master and friend Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768-1848), left Brazil toward Paris to complete the artistic training he had acquired at the newly established Imperial Academy of Fine Arts (Aiba) in Rio de Janeiro. He leaves behind his country’s capital city, which he had known a few years before, after leaving his hometown, Rio Grande de Sao Pedro. Rio de Janeiro was in turmoil, filled with the uncertainties arising from the abdication of Emperor Pedro I (1798-1834), which had occurred a few months earlier. It was the capital city of a new country where everything, including history itself, was only starting.

In Paris, at the time of the July Monarchy, he attends the studio of Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835[3]), which he leaves for economic reasons to attend architecture classes by François Debret (1777-1850), the brother of his former master at the Brazilian academy and a member of the Institut de France. Through his Apontamentos biográficos (1858)[4], we know that the house of the French architect was a meeting point for important figures, including musicians, painters, and sculptors. This is when he meets, for example, Almeida Garrett (1799-1854), whom we suspect was fundamental for Porto-Alegre’s position towards Portuguese heritage in the history of Brazilian art[5].

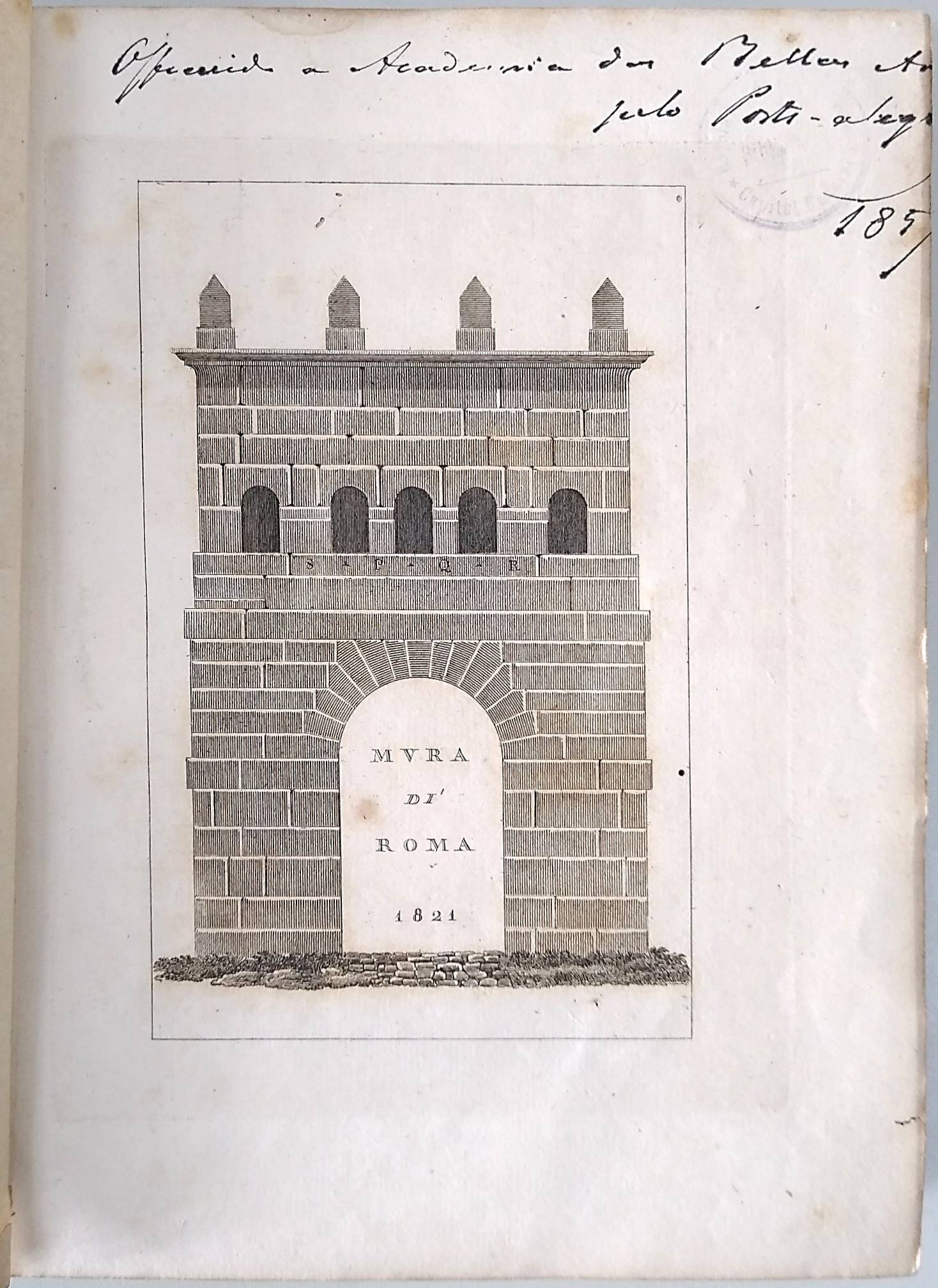

The trip to Europe will peak in Italy, a key country for any well-trained young artist or writer since at least the 18th century[6]. He leaves for the peninsula with the doctor and poet Domingos José Gonçalves de Magalhaes (1811-1882) on September 4, 1834. He remained there for just over a year, travelling through cities such as Milan, Bologna, Parma, Florence, Pisa, Siena, Naples and, above all, [7]Rome. In Rome, he attended the classes of Italian archaeologist and philologist Antonio Nibby (1792-1839), and because of this contact, we now have a copy of Nibby’s Le mura di Roma. This book is in the rare books collection of the School of Fine Arts of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro[8], a copy dedicated to Porto-Alegre, dated 1857 (Figure 1). This year was the last of Porto- Alegre’s short term as academy director[9]. As a director, he promoted a reform in the teaching of fine arts – the largest the institution went through during the Empire – and was committed to expanding the library’s collection. Within that reform, he created the degree on Historia das artes, esthetica e archeologia, a three-year program whose final year was exclusively dedicated to archaeology (UZEDA, 2000).

Figure 1 – Cover page of Le mura di Roma (Nibby, 1820), with a written dedication to Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre. Source: Collection of the Library of Rare Works of the School of Fine Arts (UFRJ – EBAOR). Photographed by the author.

Le mura di Roma

In his thesis on that very reform (2017), Marcelo Bueno writes a more detailed account of Porto-Alegre’s experience as Nibby’s student. According to Bueno, the Italian archaeologist was responsible for excavations in the Colosseum valley and part of the Roman Forum. He had been a professor at the University of Rome since 1820, and his course was perfectly in line with the standards set for studying art under academic bias, given the attention he paid to the texts of ancient authors. Future archaeologists needed to master Greek and Latin. Nibby even corresponded regularly with the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which would have led to Porto-Alegre’s interest in his [10] classes. The course program was divided into three major areas: the topographic study of places, analysis of the cultural aspects of ancient peoples and knowledge of the material heritage of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome.

Le Mura di Roma was published in 1820, in Rome, by the publisher Vincenzo Poggioli and included texts by Nibby. The drawings were by Sir William Gell (1777-1836), an English archaeologist and illustrator who lived a long time in Greece and southern Italy, having been recognised as a classical archaeologist for his contributions to the location of the archaeological site of Troy and surveys of the ruins of Pompeii.

In the preface, Nibby justifies his choice to study the walls of Rome, saying that, even though that is a material heritage of that influential civilisation, they would have always been considered less worthy of attention, traditionally overlooked because other archaeological sites were seen as having greater relevance. Conceived as a treaty, the book is divided into seven chapters besides the preface. Its contents range from the city’s foundation – which also included a mythological dimension – to the conservation of the walls in the early nineteenth century[11].

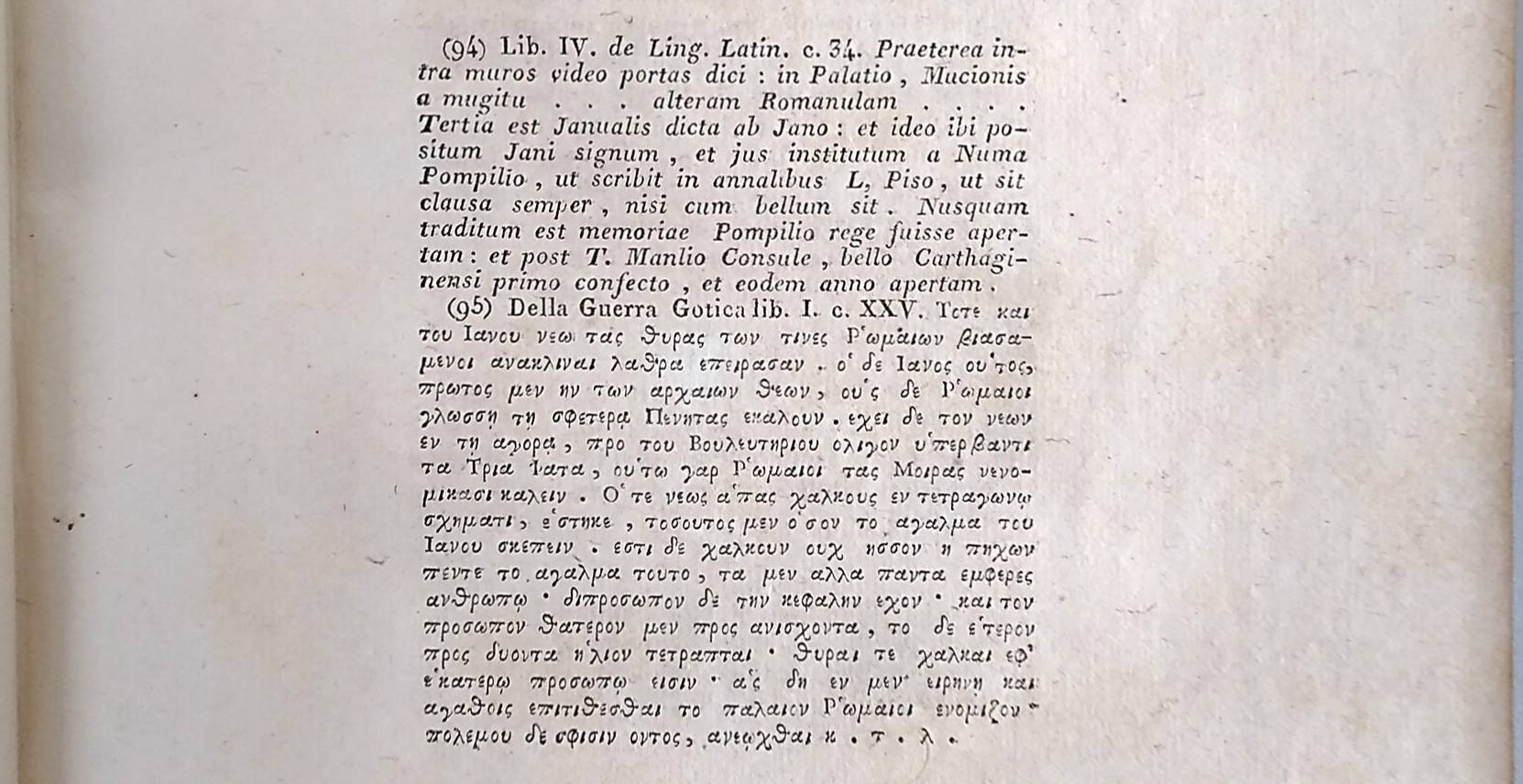

To locate the walls and their doors accurately, Nibby goes through the writings left by ancient authors, writing footnotes based on excerpts in Greek and/or Latin (Figure 2). Throughout the book, the traditional quarrel between “ancient” and “modern” that marks the construction of history in the West is thus clear, with Nibby systematically resorting to the authority of the former. The past is privileged to the detriment of the present and the future. A past that is taken as a proponent of examples that direct present actions.

Figure 2 – Footnotes No. 94 and 95 of the book Le mura di Roma (Nibby, 1820), with excerpts in Latin and Greek, respectively. Source: Collection of the Library of Rare Works of the School of Fine Arts (UFRJ – EBAOR). Photographed by the author.

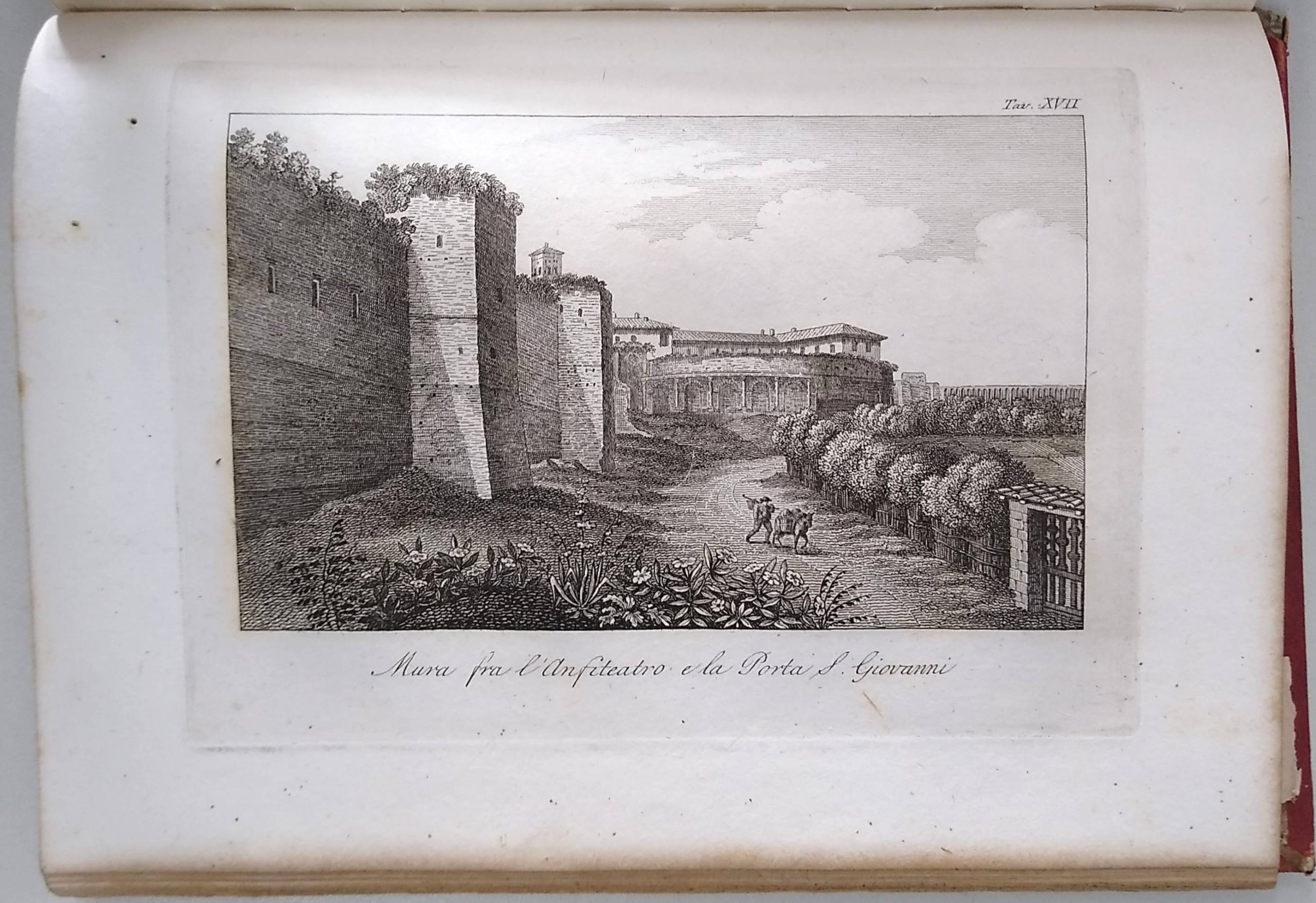

At the end of the book is an appendix with 32 drawings engraved in copper, evidencing the most exciting examples, both in terms of historical significance and their “picturesque” portrayal. Nibby highlights their accuracy in terms of information. This appendix also includes a plan of the city walls and a detailed description of each drawing. It should be noted that the word “picturesque” is recurrent in the excerpts, justifying the frameworks chosen to be represented in these engravings. Such an aesthetic category had recently been defined by the painter Alexander Cozens (1717-1786) to establish an English school of landscape painting, as described by Giulio Carlo Argan (1997[12]). According to the Italian historian and critic, this poetics, which will find its exponents in painters John Constable (1776-1837) and William Turner (1775-1851), “[…] mediates the passage from sensation to feeling: it is precisely in this process from physical to moral that the artist-educator is the guide of his contemporaries” (p. 18, italics in the original).

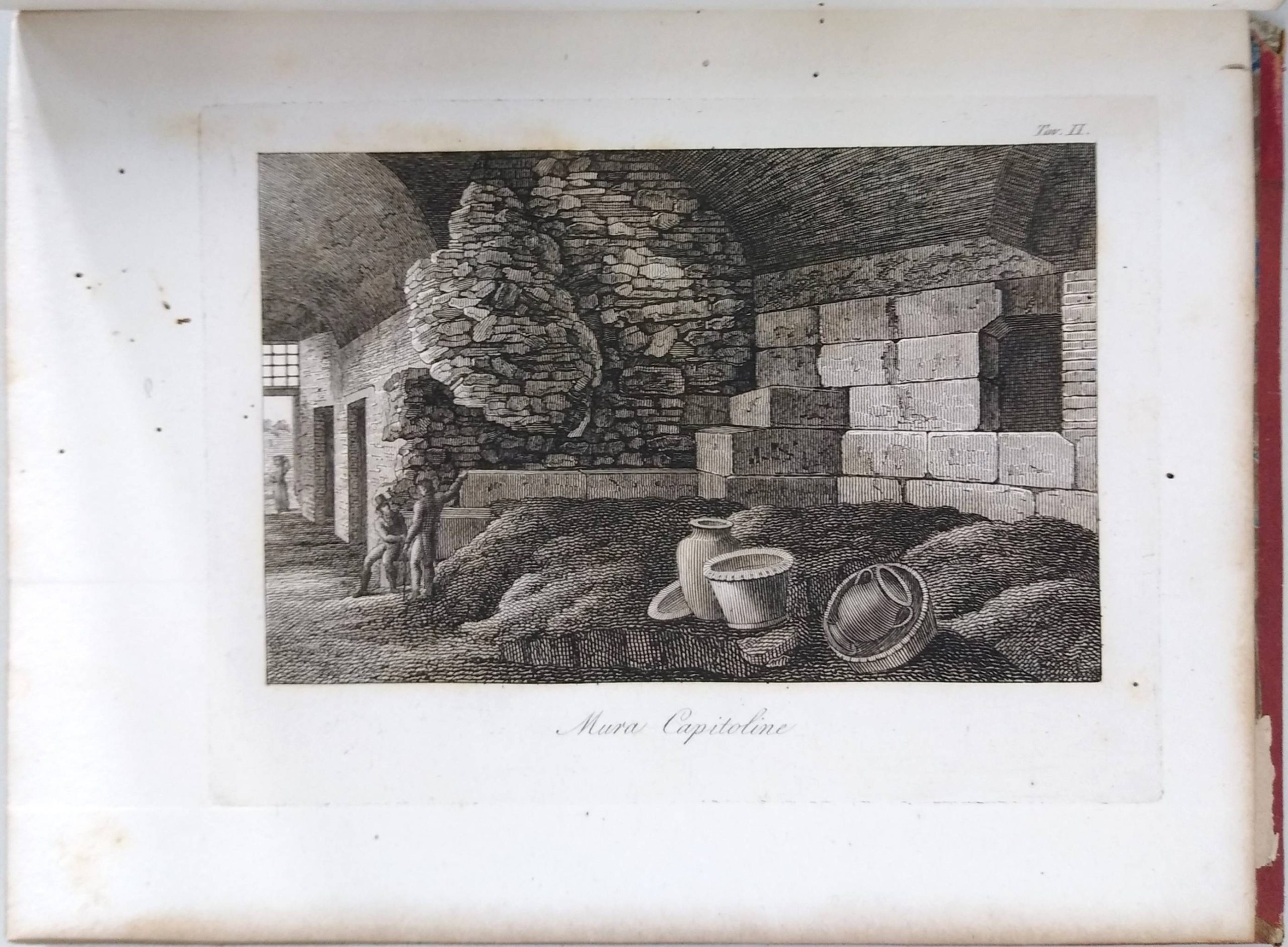

In William Gell’s engravings, the category appears as a criterion for the 14 frames of the 32 boards of the publication. In at least two of these boards, the quality of “picturesque” appears in opposition to the importance of the fragment for history, described as a “monument”. In the engravings section of the book, “sensation” and “knowledge” are thus placed as opposite categories, although they compose a single intellectual body (Figures 3A and 3B). Nibby emphasises the precision that guided the survey work necessary for the visual records – archaeology and topography were, at the time, close fields – but he is also interested in a different perspective, which seems to lead him away from the beautiful metaphysics that had interested artists in the previous century. You are now in the world. Your interest is in imperfections and peculiarities. So much so that, in many of Gell’s engravings, the scientific perspective becomes less important in the scene’s construction than the use of chiaroscuro and textures: the record is corporeal rather than abstract. The study of Le mura thus announces a significant change that was underway and gradually taking place.

Figures 3A and 3B – Tavola IX. Internal della Porta Pia and and Tavola XVII. Mura fra l’amphitheater and la Porta S. Giovanni; William Gell; 1820. Examples of the opposition between “monumental” and “picturesque”. Source: Collection of the Library of Rare Works of the School of Fine Arts (UFRJ – EBAOR). Photographed by the author.

“Sensations” – experiences becoming images – apparently led to many of the few drawings of Porto-Alegre’s travels through Italy. In the graphite Porta da Cidade de Peruggia (Figure 4), for example, the reference to Nibby and Gell’s work is evident: obviously, and besides the topic, there is also no geometric scheme based on a scientific perspective. It is not a composition exercise but the selection of a viewpoint according to nature. The contours remain, but the scene is predominantly constructed based on the different fragmented architectures, which overlap through lighter or darker spots. This mode of operation is furthered in a scene like Tivoli (Figure 5), in which nature deliberately overlaps the built structures. Drawn as a sketch, the work reveals Porto- Alegre divided between his training and experience, showing the topics the artist will opt for when he returns to America.

Figure 4 – Door of the city of Peruggia; Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre; no date; graphite, 26,5×43.0cm. Source: Artistic Collection of the Museum of Art of Rio Grande do Sul – MARGS, acquired through transfer from Julio de Castilhos Museum, 1978 and photographed by Fabio Del Re & Carlos Stein VivaFoto.

Figure 5 – Tivoli ; Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre; 1863[13]; graphite, 13,5×30,0cm. Source: Artistic Collection of the Museum of Art of Rio Grande do Sul – MARGS, acquired through transfer from Julio de Castilhos Museum, 1978 and photographed by Fabio Del Re & Carlos Stein VivaFoto.

Crossing the Atlantic and seeing America again

In A ressignificação da ideia de arquitetura: a cena americana e a educação dos sentidos (2021), Professor Margareth da Silva Pereira considers the work of the French architect Montigny to discuss the changes in the practice of architecture between the end of the eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth century.

Grandjean de Montigny (1776-1850) crossed the Atlantic fifteen years before Porto- Alegre – in the opposite direction – to found, with a group of French expatriates, the institution that would train the Brazilian artist decades later. According to Silva Pereira, the American scene would have played an essential role in the change, given the shift in the perception of antiquity which was taking place at that time. Gradually, that old quarrel between “old” and “modern” was widening to include other categories, such as “archaic” and, later, “primitive”, whose definitions depended effectively on the American experience.

Grandjean de Montigny, winner of the Grand Prix de Rome in 1799[14] and, therefore, qualified to carry out his Grand Tour through Italy, chooses to leave us the records of his tour through Tuscany in Architecture Toscane, or Palais, maisons et autres édicas de la Toscane, written in partnership with his colleague and travel companion Auguste Pierre Famin (1776-1859) and published in 1815. In several of the chosen perspectives, the preference for a rural architecture immersed in the landscape reveals his taste for the “archaic” or the “picturesque”. This evidences the main focus of who would become the first professor of architecture in Rio de Janeiro. Porto-Alegre probably knew of his master’s references to medieval and Renaissance Tuscany in a training that combined the practical and theoretical dimensions in the daily life of the studio (Uzeda, 2000).

Margareth Pereira then contrasts the Grand Tour in Italy and the Grand Tour of America; the American scene would now be in opposition to the ruins of Rome, radicalising the ongoing epistemological change already announced in works like Le mura di Roma. America re-educates the senses because strangeness and difference are heightened there. The foundation of this change seems to be the re-articulation of time and, consequently, of space, a novelty that would ultimately require a review of the very concept of history. The past as it had been presented up to then (as many examples which could be repeated) was dead, ruined. This awareness opens a “gap of time” – to adopt the terms of the French historian François Hartog (2021) – made manifest in the breach that is the revolution in France. History is now a field of possibilities re- coordinating that past, a product of future projects.

But the Porto-Alegre of the Grand Tour of Italy is not the same as the one that experiences the Grand Tour of America. The clash with the experience of his formative trip leads him, even on American soil, to a strangeness of himself and the others. The “feeling of not being at all”, in the words of Flora Sussekind (1990), the annoyance of seeing another in a landscape that remains the same indicates a change of another order, of intimate contours.

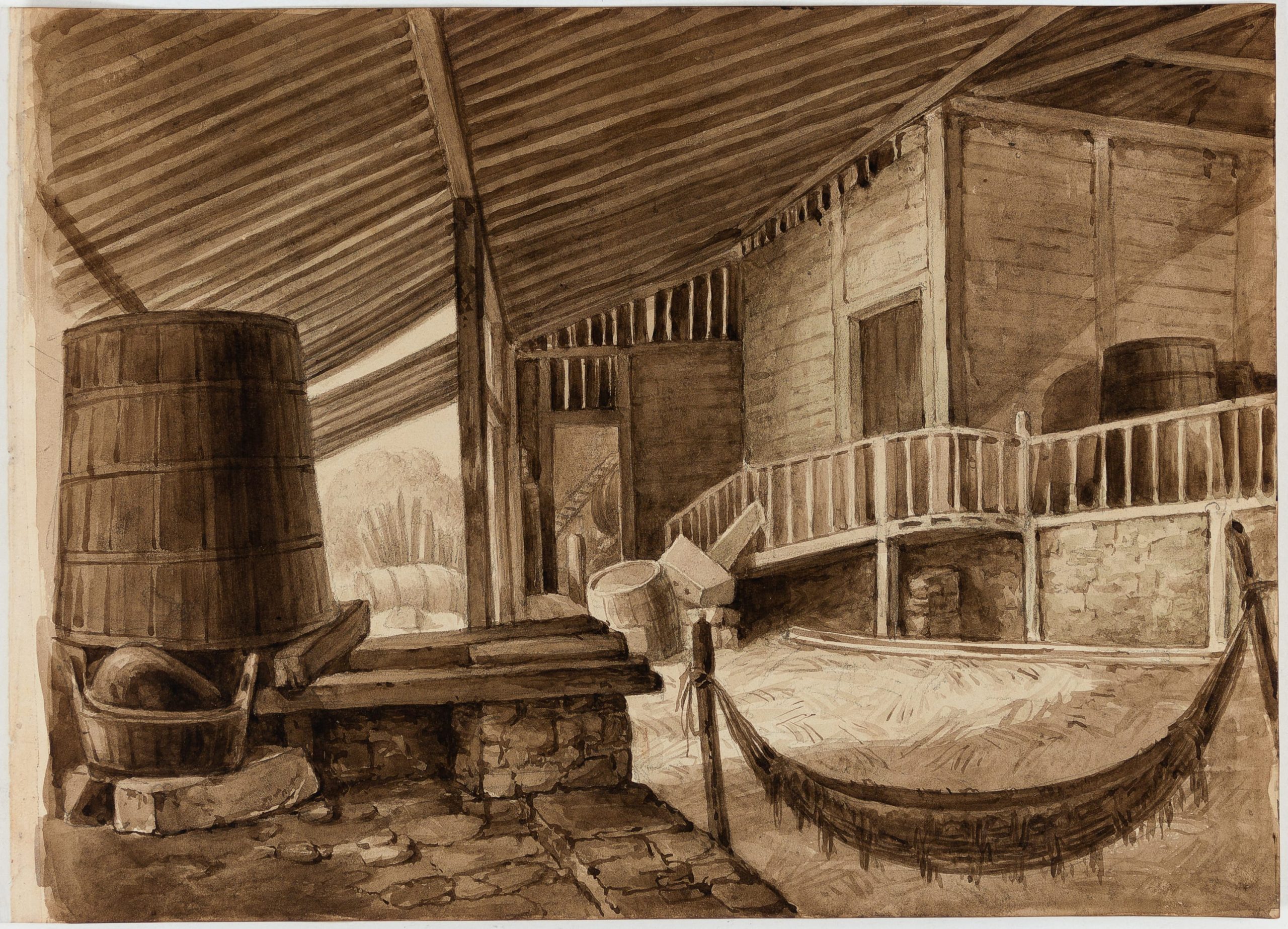

His questions will allow, in our opinion, a more mature knowledge of archaeology than what he had learned from Master Nibby. This knowledge is evident in his records of the Brazilian nature of the 1850s. The issue is perhaps more simply placed in scenes where human artefacts are the protagonists. These are much closer to William Gell’s records (Figures 6A and 6B). Here, the concept of “picturesque” (or “archaic”) is present, the tools of archaeology prove helpful, and the author’s interest focuses on the fragmentary.

Figures 6A and 6B – Estudo de interior(attributed); Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre; no date; graphite and sepious watery on paper, 21,2×29,9cm and Tavola IX. Internal della Porta Pia and Tavola II. Mura Capitoline; William Gell; 1820. Sources: Album by Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre / Martha e Erico Stickel Collection / Instituto Moreira Salles Collection and Collection of the Library of Rare Works of the School of Fine Arts UFRJ – EBAOR, photographed by the author.

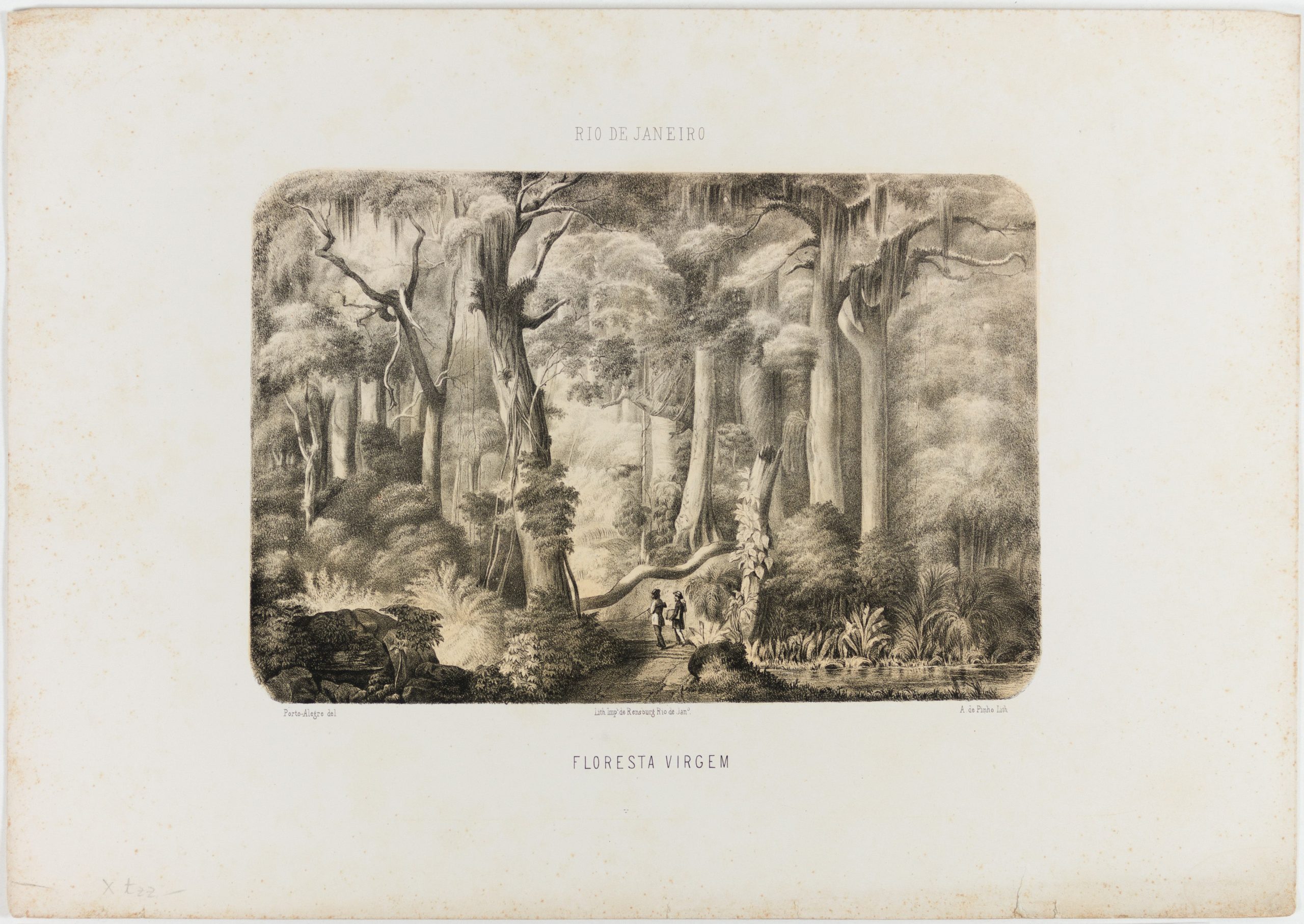

Yet, it is in the careful observation of nature, so essential for the construction of a visual repertoire that corresponds to an idea of Brazil, that the contribution of archaeology, not as a field but as an archaeological perspective, trained by the Grand Tour of Italy and transformed by the Grand Tour of America becomes evident. Among his different studies, the most relevant is certainly Floresta virgem, from 1856[15](Figure 7), a critical exercise on the botanical inaccuracies of Fôret vierge du Brésil by the Count of Clarac (1777-1847) and shown in the 1819 Exhibition. It is ultimately a question: considering a traditional conception of the past that moves continuously backwards and, consequently, is viewed as a pillar for future narratives, where are we? We need to shift to be right before historical time. This is the “timeless landscape” Professor Sussekind (1990) refers to. Thus, the conditions are met to define “primitive”, a concept devised from the first contacts between Europe and America, which now is set side by side with the traditional ideas of “ancient” and “modern”.

Figure 7 – Rio de Janeiro. Floresta virgem; Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre; Antonio de Pinho (engraver); c. 1856; lithography on paper, 18,6×27,6 (drawing) and 31,7×45,0 (support). Source: Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre / Martha and Erico Stickel Collection / Moreira Salles Institute Collection.

On his trip to Italy, Porto-Alegre realised the past could not be repeated. Just as each time and culture is unique, so is what they produce. However, on his return to America, the past is clearly understood as the possibility of free exercise. And this is how the past can be redesigned. Its redesign is urgent. Consequently, there is an effort to reposition the past in relation to the present based on a reflection of the intentions of the future, which are now at stake.

This perspective extends to Porto-Alegre, the historian: in the 1850s, more specifically, in 1856 – the year he published Floresta virgem – Porto-Alegre led his company Iconographia Brazileira (1856) to creating a history of national art. This requires him to include, in his list of great Brazilian men, artists not formally and academically trained, many of whom were black, who lived in a society where there was slavery and did not like manual labour. An example of this is his text Memória sobre a antiga escola de pintura fluminense. The following excerpt, extracted from Memoria, evidences how Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre’s training in archaeology was necessary for his historiographical work:

“Archaeology has chosen a path so safe that, despite erroneous traditions, it can, based on the ruins of a temple, the remains of its walls, its structure, the fragments of its architecture, its work, the symbolic expression of its sculptures, a medal, a casket, an encaustic, and by a painting on its wall, or a soffit, combine these elements, compare them with previous facts, and thus verify the year it was built and correct its history. Descartes was the creator of this new science when he said that the main reason behind human progress was not only tradition but analysis.” (p. 548-549, our emphasis)

To connect the two hemispheres

Bringing to the foreground the construction of knowledge activated by the crossing of the Atlantic means paying attention to a transatlantic culture that finds conditions for formulation precisely in the processes of encounter, negotiation and reconfiguration that characterize the interaction between cultures. In the case of Porto-Alegre, criticism and historiography result from having crossed the Atlantic twice, from the connection between the two hemispheres. This bold widening of perspectives, fundamental to building an operative past, is due to the awareness of the passing of time and the resulting possibility of re-coordinating historical time.

Somewhat similar to the epiphany of young Lucio Costa (1902-1998) – “arriving there, I fell completely into the past in its purest sense; a past of truth that I ignored, a past that was entirely new for me. It was a revelation: […]” (Costa, 2018: 27). These words were written when he faced America on his trip to Diamantina in 1924, exactly ninety years after Porto-Alegre’s Italian tour. The attention to specific historiographic issues has existed longer than the literature has described.

As we know, Lucio Costa, born in Toulon, studied in Newcastle and Montreaux[16]. Therefore, we are speaking about men whose biographies are blended with the crossings they have undertaken, either compulsorily or voluntarily, and which have allowed them to weave understandings of the other and themselves. Men who, between “image colonisation and globalization”, to use Roger Chartier’s words (2001), were active agents in constructing and confronting the issues of their own time.

Finally, we will transcribe the words of Francisco de Salles Torres Homem (1812-1876), who, at 22, says, in a letter to his friend Porto-Alegre on the eve of his departure toward Italy, that he, Porto-Alegre, had been born for movement. Many intellectuals – himself included – gained perspective and built their poetics by travelling between Europe and America.

“We are made for movement and progress; without movement, there is no happiness. Providence, by giving us pleasure, has aimed less at sweetening the bitterness of life than at blossoming the capacities that it had planted in the human heart and spirit and that the stillness of the soul, in which philosophers have inscribed human happiness, is not death, but the progressive and regular movement of life: that is what nature gave us! It is perhaps part of human imperfection, but we must confess that it is adapted to our earthly destiny, which is development, not stillness.” (SQUEFF, 2014: 61)[17]

Bibliography

ANDRADE, Rodrigo Mello Franco de – Araújo Pôrto-Alegre, precursor dos estudos de história da arte no Brasil. Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro. v. 184, n.° 8, jul./set. 1944, p. 119-133. Disponível em: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_G9pg7CxKSsRUdHZUtwOGstWmc/view?resourcekey=0-n8dOB5wjZV7_XaIKD8qFRw [Consult. 23/08/ 2023]

ARGAN, Giulio Carlo – Arte moderna: do Iluminismo aos movimentos contemporâneos. Tradução de Denise Bottmann e Federico Carotti. 2ª ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1992 [Original de 1988].

BLOCH, Marc – Pour une histoire comparée des societés européennes. Revue de synthèse historique. Paris, v. 46, n.° 20, Déc. 1928, p. 15-50.

Disponível em: http://www.iheal.univ-paris3.fr/sites/www.iheal.univ-paris3.fr/files/Pour%20une%20histoire%20compar%C3%A9e%20des%20soci%C3%A9t%C3%A9s%20europ%C3%A9ennes%20%28Bloch%29.pdf [Consult. 08/09/ 2023].

BRASIL – Decreto n° 1.603, de 14 de maio de 1855. Dá novos Estatutos á Academia das Bellas Artes. In Coleção de Leis do Império do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Na Typographia Nacional, 1856. Tomo XVIII, parte II, p. 402-430. Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/atividade-legislativa/legislacao/colecao-anual-de-leis/copy_of_colecao5.html [Consult. 29/08/2023].

BUENO, Marcelo da Silva – Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre e a reforma de 1854-55 na Academia Imperial das Belas Artes: projeto visionário ou ideia fora de lugar? Rio de Janeiro: s.n., 2017. Tese de doutorado. Disponível em: http://www.hcte.ufrj.br/docs/teses/2017/marcelo_da_silva_bueno.pdf [Consult. 29/08/2023]

CHARTIER, Roger – La conscience de la globalité (commentaire). Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. Paris. v. 56, n.°1, 2001, p. 119-123. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.2001.279936. [Consult. 29/08/2023]

CHARTIER, Roger – O mundo como representação. Tradução de Andréa Daher e Zenir Campos Reis. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Avançados. São Paulo, v. 5, n.°11 1991, p. 173-191 [Original de 1989]. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40141991000100010 [Consult. 09/09/2023]

COSTA, Lucio – Registro de uma vivência. 3ª ed. São Paulo: Edições Sesc: Editora 34, 2018 [Original de 1995].

DOSSE, François – Preface. In L’histoire em miettes: des Annales à la “nouvelle histoire”. 3ª ed. Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2010 [Original de 1987], p. I-IX.

HARTOG, François – Regimes de historicidade: presentismo e experiências do tempo. Tradução de Andréa Souza de Menezes, Bruna Beffart, Camila Rocha de Moraes, Maria Cristina de Alencar Silva e Maria Helena Martins. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2021 [Original de 2003], (Coleção História e Historiografia).

KOVENSKY, Julia; SQUEFF, Leticia, orgs – Araújo Porto-alegre: singular & plural. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2014.

MONTIGNY, Auguste Henri Victor Grandjean de; FIMIN, Auguste Pierre – Architecture toscane, ou palais, maisons, et autres édifices de la Toscane, mesurés et dessinés par A. Grandjean de Montigny et A. Famin, architectes, anciens pensionnaires de l’Académie de France, à Rome. Paris: P. Didot l’aîné, 1815. Disponível em: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1067157/f1.planchecontact [Consult. 29/08/2023]

NIBBY, Antonio – Le mura di Roma. Disegnate da Sir William Gell; illustrate con testo e note da A. Nibby. Roma: Presso Vincenze Poggioli Stampatore Camerale, 1820.

PEREIRA, Margareth da Silva – A ressignificação da ideia de arquitetura: a cena americana e a educação dos sentidos. 2021. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9iZgnj747S0 [Consult. 29/08/2023]

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. DEPARTAMENTO DE ARTES – Uma cidade em questão I: Grandjean de Montigny e o Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: PUC: FUNARTE: Fundação Roberto Marinho, 1979 (Catálogo de exposição).

PORTO-ALEGRE, Manuel de Araújo – Apontamentos biográficos. In Kovensky, Julia; Squeff, Leticia, orgs. Araújo Porto-alegre: singular & plural. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2014, p. 341-351.

PORTO-ALEGRE, Manuel de Araújo – Contornos de Napoles, fragmento das notas de viagem de um artista. Nitheroy, Revista Brasiliense: Sciencias, Lettras e Artes. Paris. v.1, n.°2 (1836), p. 161-213. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=700045&pesq=n%C3%A1poles&pagfis=396 [Consult. 29/08/2023]

PORTO-ALEGRE, Manuel de Araújo – Iconographia brazileira. Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro. v. XIX, n.°23 (1856), p. 349-378. Disponível em : https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_G9pg7CxKSscjhZS2JHaS1WcUE/view?resourcekey=0-KAs-B6wrbtJVHEJjjrXlXw [Consult. 29/08/2023]

PORTO-ALEGRE, Manuel de Araújo – Memoria sobre a antiga Escola de Pintura Fluminense. Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro. v.III, n.°12, 1841) p. 547-556. Disponível em: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_G9pg7CxKSseS13dWdnY29Oc2s/view?resourcekey=0-H34DBYsUUU5wHD1zVVrNcQ [Consult. 29/08/2023]

REVEL, Jacques (Org.) – Jogos de escalas: a experiência da microanálise. Tradução de Dora Rocha. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fundação Getulio Vargas, 1998 [Original de 1996].

RIEGL, Alois – O culto moderno dos monumentos: a sua essência e a sua origem. Tradução de Werner Rothschild Davidsohn e Anat Falbel. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2014 [Original de 1903].

SQUEFF, Letícia – A Grand Tour de um brasileiro: a importância da Itália nas ideias de Manuel de Araújo Porto-alegre. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas. Belém, v. 12, n.°2, maio/ago 2017, p. 377-387. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/bgoeldi/a/c36ctCKQ5q5gvgqTH8nQQhn/?lang=pt [Consult. 29/08/2023]

SÜSSEKIND, Flora – O Brasil não é longe daqui: o narrador, a viagem. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1990.

UZEDA, Helena Cunha de – O ensino de arquitetura no contexto da Academia Imperial de Belas Artes do Rio de Janeiro: 1816-1889. Rio de Janeiro: s.n., 2000. Dissertação de mestrado.

Notes

-

See the inaugural text by Marc Bloch, Pour une histoire comparée des societés européennes, published in 1928.

-

“The history of connected stories cannot ignore rigorous reflection on the categories of analysis most adequate to your project. What is the relationship between appropriation and acculturation, between inventive reuses and cultural uprooting? How can you describe the processes of ‘interaction’ or ‘negotiation’ (an expensive term both to the social world’s micro-history and new historicist literary criticism) as they operate in relations of domination or exchange? Furthermore, where do image colonisation and globalization culturally cross?” (free translation)

-

On Porto-Alegre’s training by Baron Gros, see Bueno, 2017.

-

Apontamentos biográficos, written in the third person, were published by Jornal do Commercio on May 19, 1922. The originals were given to the Brazilian Academy of Letters and published in Revista da ABL, Volume XXXVII, Year XXII, n. 120, December 1931 (Bueno, 2017).

-

The links between Garrett’s projects in the field of literature and Porto-Alegre’s in art history studies have yet to be studied. The ballad poem Adozinda, written in 1828, Garrett’s first attempt at collecting traditional Portuguese novels, is mentioned in letters exchanged between the Portuguese poet and Porto-Alegre. These letters can be found today in the collections of the Moreira Salles Institute in Rio de Janeiro and Real Gabinete Português de Leitura. Porto-Alegre’s feelings for Garrett seem fundamental to appease the malaise of the inescapable positioning of Portuguese heritage in the history of the newly independent nation.

-

Professor Margareth Pereira (2021) considers Brunelleschi (1377-1446) as the first to go on the Grand Tour but refers to how this social practice became vital for writers, architects and artists in the 18th century.

-

You cannot visit Venice and Turin; there is a morbus cholera epidemic there (see Apontamentos biográficos).

-

In the only study on Araujo Porto-Alegre’s travels through Italy, historian Leticia Squeff (2017) reminds us that few and sparse records remain about this period of his life. In his Apontamentos biográficos, Porto-Alegre mentions that part of his work disappeared in a suitcase he lost in Civitavecchia. Still, a few drawings have survived, as we will see later.

-

The artist took the position on May 11, 1854, at the invitation of Emperor Pedro II (1825-1891), held in 1853.

-

Leticia Squeff (2017) reminds us that much of Nibby’s work was dedicated to describing Rome’s monuments and those in the city’s surroundings. Thus, his publications became travel guides for scholars and those interested in classical culture who were doing the Grand Tour. Squeff mentions our topic – the importance of learning with Italian archaeologists for Porto-Alegre’s education. However, while Squeff focuses on the intellectual prestige that Porto-Alegre achieves after his Italian tour, our interest lies in how training in archaeology contributed to the repositioning of historical time as evidenced in his graphic, pictorial and textual production.

-

Thus the chapters are entitled: (i) Fondazione di Roma, e cangiamento del recinto di essa dai tempi di Romulo al Regno di Servio Tullio; (ii) Delle porte di Roma avanti il Regno di Servio Tullio; (iii) Del recinto di Servio Tullio, e del Pomerio; (iv) Delle porte del recinto di Servio Tullio; (v) Recinto di Aureliano; (vi) Recinto attuale di Roma, sua storia dai tempi di Onorio fino a’di nostri giorni; (vii) Stato attuale delle mura di Roma.

-

We should discuss here the fundamentals of this aesthetic category, as pointed out by Argan: “[…] 1) nature is a source of stimuli to which correspond sensations the artist clarifies and conveys; 2) visual sensations are presented as lighter, darker, differently coloured spots, and not in a geometric scheme such as that of the classical perspective; 3) sensory data is naturally common to everyone, but the artist uses his mental and manual technique, and thus guides the experience that people have of the world, teaching how to coordinate sensations and emotions, and also taking into account the educational function that seventeenth-century Enlightenment attributed to artists; 4) Teaching does not consist in deciphering the object, which would destroy the primary sensation, but in clarifying the meaning and value of the sensation, in view of a non-notional or particularist experience of the real; 5) The value that artists seek is variety: the variety of appearances gives meaning to nature as the variety of human cases gives meaning to life ; 6) the artist no longer seeks universal beauty, but the particular, the characteristic; 7) the characteristic is not captured , but rather with wit or the promptness of the mind, which allows to associate or ‘combine’ ideas-images, even very diverse and distant.” (p. 18, our emphasis).

-

Although the date 1863 is included in the technical data, the drawing was probably made by Porto-Alegre during his formative trip to Italy. The drawing is also used by Leticia Squeff (2017) as a reference to study the period.

-

Awarded the prize along with Louis-Sylvestre Gasse (1778-1833). Montigny left for Rome two years later to enjoy the award, remaining there for four years before returning to France in 1805 (Pontifícia Universidade Católica of Rio de Janeiro. Department of Arts, 1979).

-

Lithograph by Antonio de Pinho Carvalho (?-1895) included in Pieter Godfred Bertichen’s album O Brasil Picturesco e Monumental (1796-1866) (Kovensky; Squeff, 2014).

-

His father, Joaquim Ribeiro da Costa (1858-1937), was an admiral of the Brazilian Navy’s corps of naval engineers and constantly travelling.

-

The letter belongs to Manuel de Araujo Porto-Alegre’s album, part of the Martha and Erico Stickel collection, kept at Instituto Moreira Salles in Rio de Janeiro. The excerpt was reproduced here by Kovensky’s transcription.